As with everything in life, things are always changing. The dairy industry is no different. New technology, new business processes and new infrastructure allow and force businesses to evolve. Dairy is no different and has been changing and evolving since its inception. What has driven the changes?

Improved transportation, sanitation, pasteurization and refrigeration have played a big part, but many other things have also entered into the current evolution. Consumer preferences have changed, and new technologies have altered the way milk is produced, distributed, processed and marketed. Economics have also greatly changed, and increased competition has forced the need to be cost-competitive.

This article will review how the current U.S. payment systems for producer milk are influenced by international events. Producers are used to volatility caused by national events. However, the evolution to an even broader international market has caused further disruption within the U.S. milk-pricing process.

U.S. producer milk prices are determined by a complex analytical process which is based on the domestic value of four dairy commodities – cheese, butter, dry whey and nonfat dry milk. The linkage of international events to the analytical process of pricing milk adds a new dynamic.

Producers may not always be aware of international events that can influence their domestic producer milk prices, but these events can and are having a significant influence. In fact, exports and imports are now creating more volatility than domestic events.

Today, there are three major dairy exporting entities. The EU, where dairy began; New Zealand, where as much as 95 percent of milk is exported in various forms; and the U.S., which has in the last decade joined the ranks of major dairy exporters. Behind these three major exporters are many others, such as Australia, large countries like India and many evolving Latin American countries.

In 2014, the U.S. exported about 15 percent of the dairy solids it produced. Imports were mostly niche items like specialty cheeses. Since then, the scene has changed drastically.

Of the four dairy commodities used to price U.S. producer milk, two are primarily export items: dry whey and nonfat dry milk. Because these two products are mostly exported, the values are subject to international competitive prices.

On the other hand, cheese and butter produced in the U.S. is largely consumed in the U.S., and pricing is more dependent on domestic factors.

Because nonfat dry milk is primarily exported, the international market price will dictate the domestic price as determined by NASS. In 2013-2014, there was an international shortage of nonfat dry milk. International prices were high, and the U.S. was able to ship significant volumes at good prices. Nonfat dry milk prices are the basis for Class IV milk prices.

Therefore, the high nonfat dry milk price drove the Class IV milk price above the Class III price and, by the analytic pricing processes, then became the basis of Class I milk pricing. The Class IV price is also used to calculate the Class II price, so prices of Class II milk were also high. As a result, producer prices in 2013-2014 were healthy. Exports were a positive factor during this time period.

In 2014, the EU was hard-hit when Russia banned imports of EU dairy products and, as a result, the EU flooded the international markets with nonfat dry milk. Additionally, China reduced its purchases, and New Zealand lost sales from its best customer. Nonfat dry milk was in oversupply, and international prices fell.

Because the international price dictates the U.S. domestic price, domestic U.S. nonfat dry milk prices also fell. Class IV, Class I and Class II prices fell because of the linkages between formula prices, leading to lower producer milk prices. This relationship is pretty simple to follow. Today, the U.S. exports about the same quantity of nonfat dry milk as in 2013-2014 but at much lower prices.

The linkage between the international markets and the U.S. domestic markets for cheese and butter are a bit more complicated. Cheese and butter produced in the U.S. is 90-plus-percent consumed in the U.S.

The mechanism by which the international markets influence the domestic markets is different than that just described for nonfat dry milk. In essence, the world market’s cheese and butter pricing influence is a two-step process.

Cheeses like cheddar and mozzarella are international commodities and are therefore largely interchangeable. So if a cheese processor wants to use cheddar to create a processed product like American cheese, it can use most any cheddar from any location as long as it meets specifications.

There are some limitations on import volumes, but the market is fairly open due to many trade agreements. Therefore, if a processor can import blocks or barrels of cheddar at a better price than from a U.S. manufacturer, he will buy it and use it. That is the essence of capitalism as applied on an international basis.

Also, if the international market for cheese is lower-priced, U.S. exports will suffer in lower-volume trading unless the prices are reduced to match international prices. Currently, there is an abundance of cheese from the EU and New Zealand that is lower-priced. In 2014, the U.S. had three major customers for cheese – Mexico, South Korea and Japan.

By 2016, the markets to Japan and South Korea have been largely taken by other competitors. Exports of cheese to Mexico have increased, but that increase cannot begin to make up for the losses from exports to Japan and South Korea.

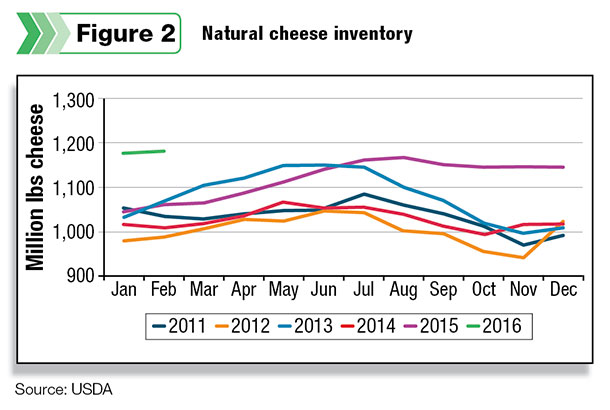

With fewer cheese exports and more cheese imports, the stockpiles of U.S. manufactured cheese have grown, as reflected in Figure 2. With the growth in inventories, the U.S. cheese market has become a “buyer’s market” with lower prices.

When cheese prices fall, the lower price is partially passed on to consumers. With lower prices, demand is elastic, and consumption will increase. However, this increase is small and cannot totally absorb the growing inventories caused by reduced exports. Only a reduction in cheese manufacturing will reduce the stockpiles.

When price for cheese falls in the U.S., the Class III milk price also falls, with a 96 percent correlation between the two.

Butter should follow a pattern similar to cheese, but currently there is a different “twist” to the international influence on domestic butter prices. All the same factors apply for butter as apply for cheese, but they are working differently. Butter churned in the U.S. is almost entirely consumed domestically.

Exports of butter are down to essentially nothing as the international prices are well below the U.S. price. Imports are way up as butter processors find much less expensive butter on the international markets. However, with that said, the domestic price for butter as determined by NASS is extremely high. How is this possible?

Unlike cheese production, U.S. butter churning has significantly reduced production. This has kept domestic inventories very tight, and domestic butter prices are therefore high.

With international trade agreements like the North American Free-Trade Agreement in effect, the U.S. dairy industry will continue to see an increasing international influence on domestic dairy prices. This will add volatility to pricing.

Currency fluctuations also have a big influence. As the U.S. dollar gets stronger, it is more difficult to compete globally on commodities. The euro used to be valued around $1.30 per euro. Currently, it is just more than $1.10 per euro. If U.S. cheese was priced at $1.50 per pound, it would have cost €1.15 per pound but now would be priced around €1.36 per pound, a significant increase.

The U.S. dollar is currently strong against most all other major global currencies, and a strong currency creates an international pricing penalty for the country with a strong currency.

As the U.S. dairy industry continues to see increasing participation in the global markets, the key to success will be the ability to be a low-cost producer of dairy solids. The key word in that sentence is “solids.” Water cannot be economically shipped. The international markets depend on products that contain a minimal amount of water.

Frankly, this is consistent with the domestic trends of less fluid milk consumption and increased consumption of products like cheese and yogurt that depend on milk solids for their processing. So the real challenge is not to be a low-cost producer of milk but a low-cost producer of solids.

As always, many people wish for the “good old days.” However, the clock does not go backward. Expanding geographic influence has been the norm for centuries, and it is just continuing that very long-term trend. It is necessary to learn to run a dairy business not just in the current environment but in the future environment as well. PD

-

John Geuss

- John Geuss Consulting

- Email John Geuss