Editor’s note: This article is the first in a two-part series featuring the steps to a successful transition period. Dry cow nutrition and management of the dry dairy cow has been extensively researched over the last 25 years.

Although nutritional requirements during this phase are fairly simple, the sudden transition from nonlactating to lactating state – as well as the physiologic and metabolic processes associated with it – make the transition period a fascinating and important stage of the dairy cow’s production cycle.

For some researchers, the transition period (three weeks before calving through three weeks after calving) has been considered the most critical and stressful phase of the lactation cycle.

At its beginning, cows may start to experience depression in dry matter intake (DMI), which along with the increased energy requirements for maintenance, the growing fetus and the mammary gland in the last month of gestation, can lead to negative energy balance (NEB). Consequently, body fat reserves start being mobilized prior to parturition to offset the deficit in glucose.

Deficit in energy balance and fat mobilization continue after parturition as DMI in earlier lactation does not couple with the increased requirements for lactation. Thus, the transition period is characterized by decreased DMI, body fat mobilization that results in higher circulating nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), ketone bodies (mostly beta-hydroxybutyrate; BHB) production and hepatic lipid accumulation, which may lead to suboptimal transitions.

Unsuccessful transitions are linked to metabolic problems that compromise production, reproduction and health of the cow during early lactation, which, in turn, decrease the profitability of the dairy farm and increase the risk for culling of cows.

Therefore, nutritional and management strategies that promote greater DMI and decrease fat mobilization are desirable during the transition period. Cow comfort is a pivotal piece in the management strategy. For instance, researchers from University of Wisconsin proposed that the barn to house cows during the transition period should be called the “special-needs barn.”

Akin to the special teams in the NFL that have the unique task of returning the ball, this barn design delivers specific freestall and headlock measures that allow for improved comfort and maximize DMI during the transition period.

All the items mentioned above are important. I would dare to say most dairy farmers in the U.S. know about them. So why haven’t we stopped talking about the transition period? Perhaps sometimes we can get nowhere if not focusing on the right things.

For example, having a special- needs barn or a specific diet does not guarantee the transition period will be successful. We must focus on things that reflect relevant aspects of the transition period.

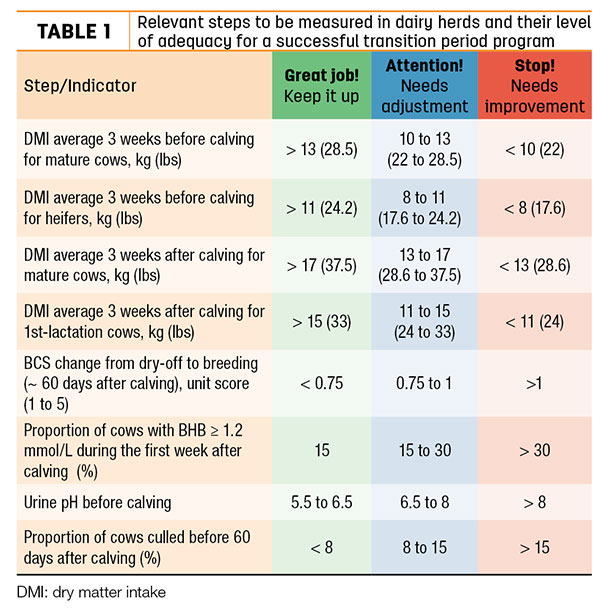

Our objective in this article is to highlight practical outcomes to be measured that can help dairy farmers and consultants keep track of the transition cow program. To do that, we have selected the 10 steps with our recommendations on where dairy farms should stand (Table 1).

In a future issue we will talk about the next five. Here are the first five:

1. Dry matter intake (DMI)

There is little evidence that milk yield per se contributes to greater disease occurrence. Our group and others have established that NEB is primarily a function of DMI and not milk production early postpartum. In that research, cows at three weeks after calving that produced 50 pounds of milk per day were at the same energy balance as cows that produced 90 pounds of milk per day.

However, cows with greater DMI had improved energy balance (less NEB). Cows have the genetic drive to produce milk at all costs. Therefore, it is very important to measure DMI of cows during the transition period to prevent NEB and consequently, metabolic disorders and reproductive failure.

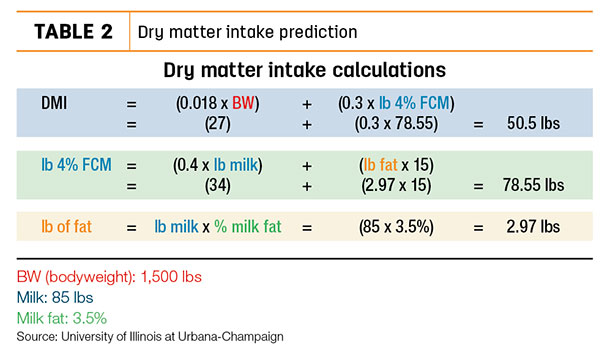

There are equations that can be used to predict the potential DMI cows should be achieving. We give an example for a cow with 1,500 pounds of bodyweight producing 85 pounds of milk per day with milk fat at 3.5 percent in Table 2.

Always check with your consultants to make sure specific numbers are appropriate for your herd.

Always check with your consultants to make sure specific numbers are appropriate for your herd.

2. Body condition score (BCS)

Cows with excessive body lipid reserves (high body condition score, or BCS) mobilize more of that lipid around calving, have poorer appetites and DMI before and after calving, have impaired immune function, have increased indicators of inflammation in blood and may be more subjected to oxidative stress.

What constitutes “high” BCS relative to the cow’s biological target remains controversial. Recommendations for optimal BCS at calving have trended downward over the last two decades, and in our opinion a score of about 3.0 (1 to 5 scale) represents a good goal at present. Adjustment of average BCS should be a long-standing project and should not be undertaken during the dry period.

Researchers from University of Wisconsin showed that cows that either gained or maintained BCS from calving to 21 days after calving had higher (38.2 and 83.5 percent, respectively) pregnancy per A.I. at 40 days than cows that lost BCS (25.1 percent) during that same period.

Other researchers have established that cows that lost greater than 1 BCS unit (1 to 5 scale) had greater incidence of metritis, retained placenta and metabolic disorders (displaced abomasum, milk fever, ketosis), as well as a longer interval to first breeding than cows that lost less than 1 BCS unit during the transition period. Therefore we suggest that BCS change should be kept to a minimum.

3. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB)

Beta-hydroxybutyrate is a ketone body indicative of ketosis. It can be measured in the urine, blood or milk of cows. Clinical ketosis have been characterized when cows have blood BHB concentrations greater than or equal to 3.0 mmol/L (or 3,000 µmol/L or 31 mg/dL) while subclinical ketosis have been characterized as cows having blood BHB concentrations greater than 1.2 mmol/L (or 1,200 µmol/L or 12.4 mg/dL).

Early occurrence of subclinical ketosis is more likely to decrease milk yield and compromise fertility. Researchers from University of Wisconsin and Cornell found that cows with subclinical ketosis detected between three to seven days after calving were 0.7 times less likely to conceive to first service and 4.5 times more likely to be removed from the herd within the first 30 days in milk compared with cows that developed ketosis at eight days or later.

They have created a “herd alarm” and suggest to have less than 15 percent (15 cows in a group of 100 cows) of cows in a group with blood BHB greater than or equal to 1.2 mmol/L in the first week after calving.

4. Urine pH

Milk fever (hypocalcemia) is an important problem that affects lactating dairy cows, particularly those starting their second or greater lactation. It is characterized by serum total calcium (Ca) less than 5.5 mg/dL (or less than 1.4 mM) around calving and clinical signs (downer cows). A less-recognized problem is the prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia, which has no clinical signs and is typically characterized by serum total Ca less than 8.5 mg/dL (or less than 2.1 mM).

Researchers from Universities of Wisconsin and Florida have shown that cows with subclinical hypocalcemia have increased risk for metritis, increased risk for postpartum fever, increased post-fresh BHB (1.0 versus 0.7 mmol/L), longer median days open (124 versus 109 days) and immune suppression. The most effective prevention seems to still be through dietary means.

Feeding a negative DCAD (dietary cation-anion difference) diet 21 days before calving has been shown to prevent clinical (a five-fold reduction) and subclinical hypocalcemia. The cow’s acid-base status is changed, resulting in a raised amount of calcium available in the blood.

Urine acidity is affected by these changes in the cow’s acid-base status as early as two days after the diet starts to be fed. Checking the urine pH of cows in the prefresh group can help you monitor the effectiveness of an anionic ration.

5. Number of cows culled before 60 days in milk

This one is pretty straightforward. Transition problems significantly increase the risk that a cow will be culled, so keep track where your herd is at. The goal should be to have less than 5 percent of the milking herd leaving the dairy before 60 days in milk and less than 3 percent should die before 60 days in milk (8 percent total). ![]()

-

Phil Cardoso

- Assistant Professor - Department of Animal Sciences

- University of Illinois

- Email Phil Cardoso