Despite overall declines in drug residues found in bulk milk samples, marketing and regulatory efforts continue to apply pressure to reduce antimicrobial use in livestock, including dairy herds.

“A majority of antimicrobials used on dairy farms are for mastitis treatment and prevention,” said Dr. Sandra Godden, a professor in the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine. “The marketing and regulatory pressures are leading researchers to seek new mastitis control practices to reduce antimicrobial use while maintaining or improving udder health.”

Godden outlined one such practice, selective dry cow therapy (SDCT), during the 2016 National Mastitis Council regional meeting June 30 in Appleton, Wisconsin.

First, some background.

The dry period is critical to udder health and milk quality in the subsequent lactation. In addition to vaccination programs to enhance immunity, nutrition, cow comfort and hygiene play a role in udder health.

One long-standing practice providing udder health security is blanket dry cow therapy (BDCT), the infusion of all quarters and all cows with a long-acting antibiotic – sometimes accompanied by internal or external teat sealants – at dry-off.

The rationale behind BDCT is that 20 percent to 30 percent of all quarters will develop new intramammary infections (IMI) during the dry period, and 50 percent to 60 percent of all new environmental mastitis infections during the lactation are rooted in the dry period.

“Blanket dry cow therapy helps eliminate subclinical infections present at dry-off and reduces the risk for new infections during the early dry period,” Godden said

Published research data and the USDA’s National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) Dairy 2007 report indicated up to 80 percent of all dairy producers implement BDCT. Except for minor hiccups, Dairy Herd Improvement test-day samples show bulk tank somatic cell counts, a measure of a herd’s overall udder health, have generally been declining for more than a decade.

Changing dynamics

With those udder health improvements, combined with public scrutiny of antimicrobial use, Godden and others are studying SDCT as a herd management option.

While the concept is relatively new to the U.S., it is already mandatory in the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Germany, and is being introduced by some dairy processors in the United Kingdom.

How it works

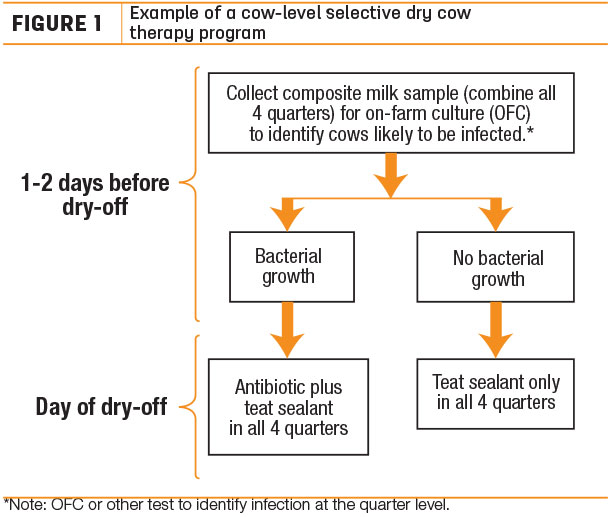

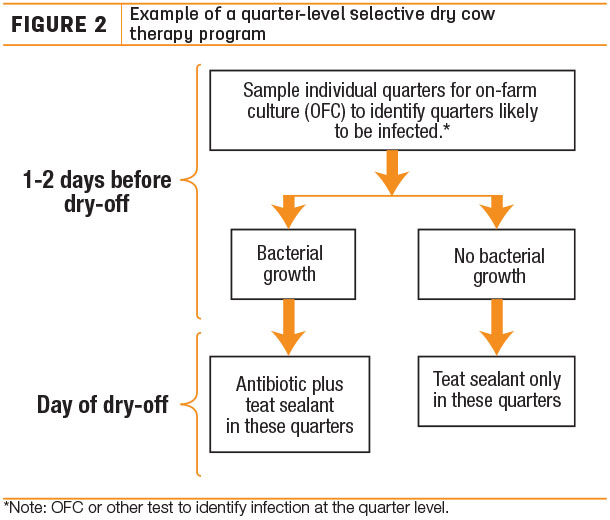

Under an SDCT program, all cows and quarters are tested at dry-off to detect IMIs. Antimicrobials are only infused into cows – or individual quarters – testing positive for an IMI. All cows or quarters – whether treated with an antibiotic or not – also receive an internal teat sealant to prevent new IMI during the dry period.

First attempts at SDCT met with limited success or, in some cases, udder health conditions worsened in subsequent lactations, Godden said. Likely factors may have been the use of imperfect on-farm screening methods or tests to identify cows or quarters requiring antimicrobial treatment at dry-off.

Indirect tests such as SCC or California Mastitis Treatment indicate the presence of inflammation but do not always indicate the actual infection status of a cow or quarter, Godden said. Using clinical mastitis history to identify infected cows or quarters requiring treatment may also miss infected udders.

New, more accurate on-farm tests, such as on-farm culturing, have higher sensitivity to identify infected cows or quarters, as compared to some of the previously mentioned tests (e.g., SCC history). Commercial rapid culture tests are available, and University of Minnesota researchers are refining the Minnesota Easy 4Sight plate, University of Minnesota, with early indications showing sensitivities over 90 percent.

A second factor contributing to early failure of SDCT programs may be a lack of tools to protect against new IMI during the dry period. Teat sealants, such as Orbeseal, are now more readily available to protect untreated quarters from new infections.

“We now have the necessary tools available for successful and economically viable SDCT programs that can significantly reduce the use of intramammary antimicrobials at dry-off, while maintaining the future udder health, production potential and well-being of the dairy cow,” Godden said.

Study results

Godden reported on two recent controlled SDCT studies, both of which successfully incorporated on-farm culturing and teat sealants. The studies reported a significant reduction in antimicrobial use while successfully maintaining the same udder health as the BDCT group.

The first, a 16-herd study in Atlantic Canada, applied SDCT at the cow level and used on-farm culturing of composite milk samples. Infected cows were treated with both a long-acting antibiotic and internal teat sealant in all quarters, while noninfected cows were infused only with the teat sealant in all quarters.

Cultures performed at dry-off and after calving revealed cows enrolled in the SDCT and BDCT programs were not different in bacteriological cures, new IMI, prevalence of IMI at calving or clinical mastitis risk in the first 120 days in milk.

A second pilot study, conducted at the University of Minnesota – St. Paul campus dairy, applied SDCT at the quarter level after using the Minnesota Easy 4Sight plate to identify individual infected quarters.

Infected quarters were infused with both antibiotic and internal teat sealant, while noninfected quarters were infused only with the teat sealant.

Cultures of all quarters at dry-off and after calving revealed that quarters enrolled into the SDCT and BDCT programs were statistically and numerically not different in bacteriological cures, new IMI and prevalence of IMI at calving. However, antimicrobial use was reduced by 48 percent in the SDCT program.

So far, economic data is limited. The University of Minnesota pilot study showed an increase in labor costs to catch and sample cows, plus the additional mastitis culture materials.

However, those costs were more than offset by reduced antimicrobial costs, yielding a net benefit of $2.62 per cow when implementing the SDCT program.

The economics won’t apply equally to all herds under all situations, and larger multi-herd studies are needed to examine the relative economic and biological success of different types of SDCT programs. However, even if SDCT programs just break even as compared to BDCT, it is important to know they can be at least economically viable.

Management challenges

Whether conducted at the cow or quarter level, SDCT success will depend on the strengths and weaknesses of your herd management team.

Depending on the test used, SDCT will require more intense labor, testing all cows – or all quarters of all cows – at dry-off to detect mastitis infections that will benefit from antibiotic therapy. More record-keeping will be necessary.

A critical decision will be what screening or diagnostic testing program will be used. If using an on-farm culture test, it will be necessary to sample the cow one to two days in advance of the intended day of dry-off.

A designated clean lab area, necessary equipment and supplies, and trained personnel to perform and interpret the results will be needed.

Infected cows (or quarters) must be correctly identified and matched to the correct treatment protocols. And staff will need training in proper, clean treatment techniques.

For herds unable or not willing to make that investment, the herd veterinarian, with the help of trained technicians, may be able to provide the service. This full-service model is already successfully being used in New Zealand to complete other routine tasks, Godden said.

As compared to low-SCC herds, high-SCC herds will have a smaller opportunity to reduce antimicrobial use in a SDCT program, since a greater proportion of cows/quarters will be infected and therefore require treatment at dry-off.

Godden suggests that it might be reasonable to consider SDCT programs in well-managed herds with a bulk tank SCC of less than 250,000 cells per milliliter.

“Farms with good udder health should consider working with their veterinarian to develop and implement a SDCT program,” Godden concluded. ![]()

-

Dave Natzke

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Dave Natzke