One of the unique disadvantages for the U.S. dairy industry in international dairy markets is the standard for milk quality. The specific standard allowed for somatic cell count (SCC) is a barrier for U.S. dairy sales to some countries and a marketing disadvantage in others.

This article will inspect these differences between the U.S. standard and the international standard for allowable SCC in some detail.

The often-cited SCC difference is that the U.S. allows milk with up to 750,000 somatic cells per milliliter where the other major global dairy exporters limit the count to 400,000 cells per milliliter. On a simplistic basis, U.S. milk appears to be of lower quality.

However, the details of how the systems are calculated narrow that difference. In both systems, the analysis is done from bulk tank milk, which includes milk from many cows.

Somatic cells primarily represent the “dead” white blood cells fighting infection. Typically, mastitis is the culprit for the high white blood cells as the cow’s body fights the infection. One of the important factors to recognize is the volatility of the somatic cell count.

When mastitis flares up in a herd – often during hot weather – and the infection spreads from cow to cow, a brief period of high counts occurs. With good management, flare-ups can be minimized and, when they occur, they can quickly be brought back under control.

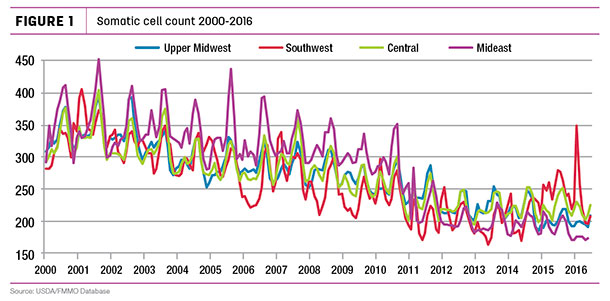

Figure 1 graphically shows how U.S. producers have lowered somatic cell count since the year 2000. The data used for Figure 1 is from the Federal Milk Marketing Order database for the four orders that pay (or penalize) for somatic cell count levels. These numbers demonstrate two things.

Somatic cell count has decreased over the 16 years this data has been collected, and second, that on average, somatic cell count is well below the 400,000-cells-per-milliliter level.

In the U.S. system, a single bad test can make a producer lose his Grade A rating. In Europe, there are two caveats that help reduce the risk of a single bad test.

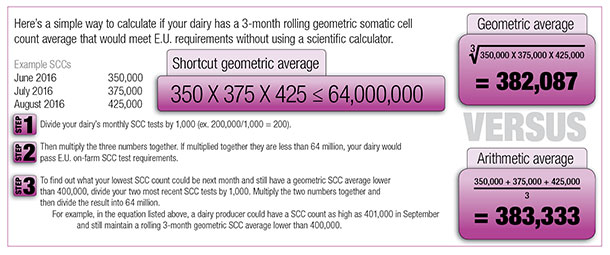

The European system uses a “geometric” average instead of an athematic average and always averages three monthly tests. The geometric average and the three-month average minimize the impact of short-term “flare-ups.”

What is a geometric average? In mathematical terms, you multiply three monthly data points together and then take the cube root of that number. This mathematical process tends to smooth the data, reducing the impact of a single high number and providing an average that is less than a simple arithmetic average.

The frequency of inspection is also different between the U.S. and Europe. For example, in the U.S., if three out of five consecutive monthly tests are above 750,000 cells per milliliter, the herd is “noncompliant.” However, in the EU, a herd must be above 400,000 cells per milliliter in four consecutive three-month geometric averages.

While a change from 750,000 to 400,000 sounds huge, geometric averaging and three-month rolling averages significantly reduce the severity of the change.

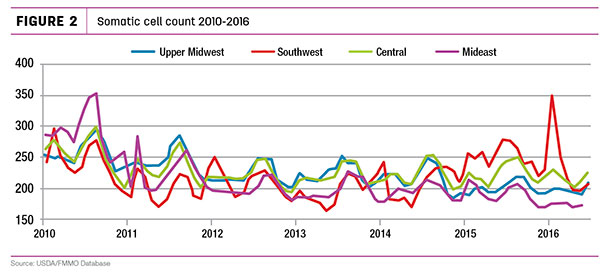

How ready is the U.S. dairy industry for a lower SCC standard? Reducing the long-term chart shown in Figure 1 to a shorter time frame does raise some concerns about the U.S. readiness for tightening standards. The last five years of data show no further improvement in lowering SCC, and there is a concerning increase with some flare-ups in the Southwest order (Figure 2).

The change in the milk quality trend is roughly consistent with the timing of the defeat of prior attempts to lower SCC standards. It’s been proven that a lower SCC can be achieved through improved management practices. Implementing these improved management practices is a matter of priorities in the busy and complicated life of a dairy producer.

The argument for not decreasing the 750,000-cells-per-milliliter standard is that somatic cells do not present a health risk. However, a higher SCC can influence shelf life, taste and cheese yield. The latter, cheese yield, is the main reason the four federal orders pay a premium for a lower somatic cell count. It has also been shown that a lower SCC will increase milk volume.

There are many processors who have already adopted the 400,000 SCC limit in order to compete on international sales and to meet domestic private label requirements. These processors and their producers have already made the transition and changed their processes to meet the international standard.

Click here or on the image above to view it at full size in a new window.

It would certainly be a major transition for all producers to meet this standard, but it would probably not be practical or acceptable to use a more demanding standard for export while maintaining a lower quality standard for U.S. consumers.

While the 400,000-cells-per- milliliter standard is often referred to as the “European” standard, it is in use by the other major dairy-exporting countries like New Zealand and Australia. No other countries have adapted the U.S. testing methods and analytical processes as their standards.

Therefore, the “European” standard has become the de facto international standard. It has spread throughout the EU as new member countries have been admitted to the EU, and dairy producers have had to change their practices to meet these standards.

The maximum SCC standards discussed above are published by the U.S. Public Health Service/FDA. There are separate standards and formulas for SCC payment in the federal milk order system. These maximum SCC standards, or any changes to them, do not influence the SCC payment system in place in the four Federal Milk Marketing Orders, which have an SCC incentive in their component payment calculations.

While there is a great deal of controversy over expanded free trade agreements, there is no doubt that the geographical boundaries for dairy products will continue to expand. To level the playing field, the U.S. must have a plan to convert to international standards so U.S. dairy products can compete in the international markets.

While any change is difficult, if the change is inevitable, it is better to have a long-term transition plan for all to the European standard than to wait for a crisis and try to deal with a double standard domestically. ![]()

-

John Geuss

- John Geuss Consulting

- Email John Geuss