Dairying is often portrayed as a very difficult career to get into for young, beginning producers. And, it is often said there is no money in dairying; dairying is too much work; dairying takes too much capital; you can’t graze dairy cows profitably; one can’t be profitable with 16,000 to 18,000 pounds of milk per cow; earning $25 to $50 per labor hour milking cows is not possible. The list goes on… Granted, 2009 was a very difficult year for dairy profits with the high feed costs and low milk prices. Yet, there are dairy producers in the Midwest who are making money without too much work and with lower capital requirements, even in years like 2009. Moreover, they are often earning greater than $25 per labor hour with below average milk production.

( Be sure to check out the below. )

In order to better understand this reality, Iowa State University (ISU) Extension embarked on a Millionaire Model Dairy Farm project, supported by the Leopold Center at ISU.

In 1993, I devised a model dairy farm that could assist young dairy producers to become very successful milking 80 cows on 80 acres.

Over a 25-year time period using the model, producers aimed to use a combination of labor efficiency, cow comfort, low cost facility, rotational grazing and financial management to garner a $1 million net worth.

The base plan

A feed plan was developed using 16,000 pounds of milk per cow with an estimated cow weight of 1,300 pounds and an average heifer weight of 650 pounds resulting in daily dry matter intakes of 42.60 pounds and 16.25 pounds respectively.

With a feed wastage rate of 20 percent and a herd cull rate of 20 percent, the cow and replacement needed 10.75 tons of dry matter annually.

The model uses 80 acres of a legume/grass mixture for grazing/ haying with a yield of 4 ton of dry matter per acre; 20 acres of purchased corn silage with a yield of 7.5 ton of dry matter; 150 tons of purchased hay; and 292 ton of protein and grain supplements.

Financing

The Millionaire Model Farm Plan started from bare bones investment levels. However, the investment levels started with in 2003 may not be realistic for obtaining a loan after 2009. This was the modelâs Summary and Loan Request to borrow $110,000 for:

a) Cows, 80 at $1,500 or $120,000

b) Machinery:

- Tractor $4,300

- Skid Steer $3,600

- Manure Spreader $3,000

- 4 Wheeler $1,200

- Rake $500

- Haybine $2,400

Total Machinery $15,000

c) Capital Improvements $5,000 to a rented farm

Total Capital Needed $140,000

d) Capital on Hand $30,000

Goal < 80% Borrowed

Millionaire Model growth and performance

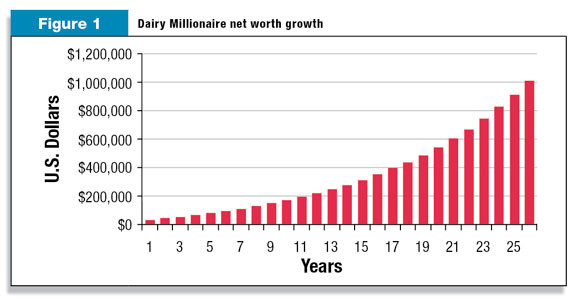

The millionaire model budget showed a beginning net worth of $30,000. The budgeted return on equity was 15 percent, which gives a 5 percent (or $1,500) higher return than the 10 percent return on net worth used in Figure 1 .

The budgeted rate of return on assets was 13 percent. With interest costs at 8 percent, and additional 5 percent ($5,500) is returned.

Adding these two together gives an addition $7,000 deposit to put towards net worth growth of 10 percent.

The growth depicted in Figure 1 is after family living and farm expenses but before taxes. Growth starts slow but the net worth grows.

Five dairy producers in Northeast Iowa and Southwest Wisconsin participated in ISU Extensionâs Millionaire Model Dairy Farm Project, several as long as 1993. These five farms were analyzed financially in 2002, 2004, 2007 and 2009.

Each of these farms grew bigger than the model over the years and thus their profitability is shown to be much higher than the 80-cow model as well. Four of the five producers achieved millionaire status within 17 years. The fifth, a dairy producer beginning in 2003, had achieved more than $300,000 of net worth in seven years.

To show the range in profit levels, 2007 data is used for each of the five farms and then compared with the 2009 average data. Over the years, the five model dairy producers made good profits in their operations. ( To see budget information for these years, click here . )

The 2007 net farm income adjusted for inventory averaged $287,759 with one farm achieving an adjusted net farm income of $410,673.

After an equity charge of 6 percent for owned capital employed on the farm, the return to labor averaged $218,629 per farm with the highest farm earning $301,013 return to labor. These farms were all operated by a husband-wife or father-son management and labor teams.

In 2007, these five model farms averaged $20.42 per hundredweight for milk sold with a cost of production of $14.05. For the purpose of comparison, the 2009 average milk price was $13.81 per hundredweight with a per hundredweight cost of production of $13.95.

It is very interesting to note that the cost of milk production on these model farms was higher in 2007 than it was in 2009, which I suspect was not true for the majority of dairy farms.

Net farm incomes in 2009, adjusted for inventory, averaged $112,278 but already paid $44,433 in labor hired. To compare this to 2007 data, all the labor costs were entered in the unpaid category. This also impacts the labor earnings per hour by approximately $1.26 for 2009, which only averaged $14.30 per hour.

After an equity charge in 2009, return to all labor would have averaged $84,789 per farm, but subtracting out the $44,433 in paid labor gives a return to unpaid labor of $40,356. With an opportunity cost of $40,000 for unpaid labor, these dairies in 2009 essentially broke even with all labor, equity and interest costs paid.

The average return to labor and management was $41.35 per hour with a range of $28.31 to $48.14 per hour for these farms in 2007. Labor efficiency is a key to success for these farms.

Each full-time equivalent of labor (FTE) is 3,000 hours. With this in mind, the average number of cows per FTE was 77 cows in 2007. Farm #3 was a rented farm with only 70 acres, which increased feed purchase expense and decreased labor costs per cow.

A very key measure is hundredweights of milk sold per FTE and these farms all sold more than 1 million pounds of milk per FTE laborer with an average for the farms selling 1.3 million pounds of milk per FTE and Farm #3 achieving 1.46 million pounds of milk per FTE in 2007.

On a per cow basis, milk per cow averaged 16,679 on these crossbred herds with a Holstein-Jersey base. The milk per cow efficiencies illustrate a profitable level that is considered poor from conventional standards.

The productive crop acres per cow average 1.56; the capital costs (depreciation and interest) averaged $598 per cow; the labor costs per cow averaged $389; the fixed costs per cow averaged $770 per cow; and the capital invested per cow averaged $7,472.

The net farm income per productive crop acre averaged $1,510 but in 2009 it was only $435 per acre. The pounds of milk produced per crop acre averaged 12,323 in 2007 and 12,437 in 2009. These per crop acre efficiencies, in addition to the FTE labor and per cow efficiencies show a highly efficient group of farms.

Financially, the rate of return on assets average 23.68 percent in 2007 but only 3.4 percent in 2009. In 2007, the operating profit margin averaged 43.21 percent and only 13.62 percent in 2009. The asset turnover ratio averaged 58.20 percent in 2007 but only 39.38 percent in 2009.

In sum, these farms showed superb profitability with 2007 milk prices but barely broke-even in 2009. They showed great profitability with milk estimated at $14 per hundredweight.

Dairy producers are encouraged to use these numbers for budgeting new or transitioning grazing operations, but remember the costs of the learning curve. Current producers aspiring to higher levels of profit can use these numbers for benchmarking their operations and goals. PD

:

Tables 1 & 2: Comparison of Individual 2007 Data and Comparison of 2007 and 2009 Average . (Click on link to download pdf.)

Case study: Millionaire Model Dairy Farm in Dubuque, Iowa (Click to open article in a new window.)

What makes a Millionaire Model Dairy Farm successful? (Click to open article in a new window.)

âExcerpts from Iowa State University Extension publication by Dr. Larry Tranel, Extension Dairy Specialist, Iowa State University

-

Larry Tranel

- Extension Dairy Specialist

- Iowa State University

- Email Larry Tranel