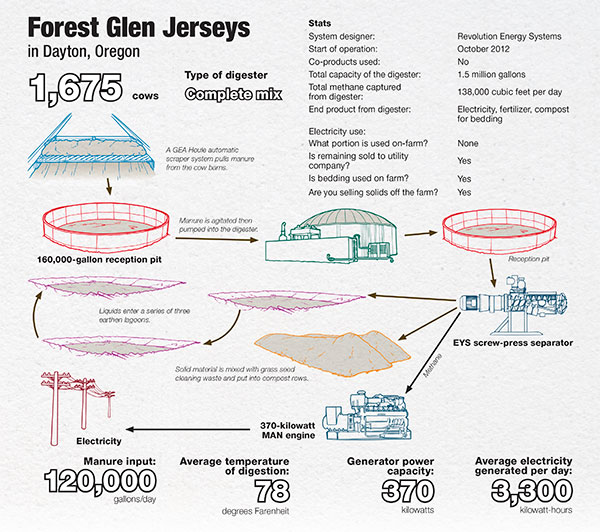

Rising conspicuously smack-dab in the middle of Oregon’s wine country near Dayton are two large, blue manure-slurry holding tanks with expandable tops – methane digesters – erected in 2012 at Forest Glen Jerseys. It’s a $2.4 million facility.

Robert Kircher, co-owner of Forest Glen Jerseys, says, “We did not pay for a penny of that. The contract is that we get the manure from our barn into a reception pit.

From there, it’s their Revolution Energy Systems’ responsibility to get it out of the reception pit and run it through the digester system.” The dairy invested in an automatic manure pen scraper to supply the ongoing manure requirement. Other than that, their only requirement was to set aside a piece of ground for the company to legally use.

Kircher explains that the methane from the digester is ultimately burned through an engine generator to produce electricity, which is pushed into the general electrical grid system to the tune of 370 kilowatts per hour, which potentially provides electricity for 300 homes per year. A small percentage of income generated from the power returns to the farm.

As the solid material is expelled into a dairy-owned tank, it passes through a screw-press separator. The liquids flow into lagoons and are later applied to pastures.

The solids are mixed with grass seed cleaning waste, which helps remove the remainder of the moisture. When the mixture reaches 150ºF, it creates a sterile product that is then used for cow bedding. Kircher says, “Another benefit we’ve noticed with using the compost is we have fewer incidents of mastitis.”

Excess solids are sold to many different biodynamic vineyards around the local area.

Pastures, vineyards, blueberry farms and hazelnut orchards now surround Forest Glen Jerseys’ cows – 1,400 at the home place and another 275 cows at a nearby farm.

“The digester virtually reduces odor to nothing, making our neighbors happy,” Kircher says. “Having a digester on the farm really seems to impress the public, letting them know we are producing power from our cows.”

Robert Kircher was about 11 years old when he was first exposed to dairying. His father, a local brew pub owner, needed someplace to go with his brewery mash, and that’s how they found Dan Bansen and his small Jersey dairy. Kircher’s father sold the mash to Bansen, who used it in the mixed ration to help grains adhere to the forages.

Thereafter, Kircher and his brothers worked for Bansen in the summers and during school vacations, and Kircher was quickly hooked. He loved the cows, loved the dairy and loved the responsibility.

After Kircher earned an ag and dairy science degree from Oregon State University, Bansen offered Kircher a management position and subsequently a partnership in the dairy. When Kircher came to the dairy, there was one flat-barn style parlor, milking 200 cows. The dairy now uses four cow barns and one double-24 parlor.

In 1997, the dairy converted to certified organic which, among other things, meant reducing the 3X milking to 2X. As an organic dairy, the cows are required to ingest 30 percent dry matter from pasture a minimum of 120 days per year. Forest Glen pastures much longer, from March through mid-October.

Grazing for that length of time requires 52 paddocks with an average 25-day to 30-day rotation. The paddocks are bordered with solid set fencing. Kircher says, “We have six different lactating groups that go out every day.

I made a pasture map and laminated it. We have one full-time guy that all he does is put the cows out and records their grazing location and times. We do strip grazing, and he manages the whole grazing operation.”

The readily available nutrients in the compost off the digester have greatly improved their pastures. “Having a digester on our farm is not only a green-energy benefit but a system that has shown to improve our manure nutrient breakdown, making those nutrients more plant-ready after going through the digestion process,” he says.

The pastures blend predominantly clover, orchardgrass and ryegrass varieties, using silage corn as a rotation crop irrigated with single-gun sets and K-line sets.

Kircher says the benefit of having all the pasture ground means they’ve been able to cut the normal ration up to 45 percent, “... and so the feed just piles up here and that saves a lot of money at the end of the day.”

Kircher says they can get five to six cuttings of alfalfa on the home place, but it isn’t first-quality hay. They also have a farm in Fort Rock, Oregon, where they get three cuttings of better-quality hay.

Some silage and haylage is stored in bags using BioMax O inoculant. They purchased a Claas shredlage processor and used it for the first time in the 2013 harvest.

The Forest Glen herd has gained a nationwide reputation for superior genetics, with a rolling herd average of 50 to 51 pounds per cow. Kircher believes a large portion of this success is due to the organic factor.

Kircher explains, “Being organic and not using antibiotics, we feel like our cows have a much stronger immune system. It’s the same way with people – if you have a healthy diet and get exercise.

Our cows get exercise walking up and down the hills and being outside on pasture, and they get grass in their ration. Most dairies are using 3X milkings, and we use 2X milkings, which are way less stress and the cows are less likely to get sick.”

In an effort to promote hoof health, Forest Glen Jerseys uses slag rock from a local steel mill on all cow lanes. The fine rock is round and doesn’t hurt the cows’ feet, as does normal regularly processed rock that sports a lot of sharp edges.

In an area quickly expanding into the blueberry and hazelnut markets, and with CAFO regulations limiting expansion, Kircher says the dairy is currently size-capped. Their goal now is to find more land to be able to grow more of their own feeds and become more sustainable.

Kircher highly praises his full-time employee crew of 36 as a key to their success, stating many of the employees have been with the dairy 10 to 20 years or more. Luis Castillo, for instance, began in 1991 as a milker.

He advanced in responsibility into managing herd health and finally taking charge of the breeding program, performing all A.I. processes. Kircher says, “You can have people who are yellers or screamers, and sometimes that’s needed, but a lot of times it doesn’t work out that great.

Luis is calm. He just lays out the plans instead of going in there and screaming. Dairies commonly have problems with milkers, but Luis takes care of that and does a good job of it.”

Luis’s wife, Christina, is in charge of the calves, regularly filling and caring for 476 hutches. Kircher claims her care and “mothering” is responsible for the low mortality rate.

Kircher says Trino Botello was another lucky find for the dairy when he and his wife came about 12 years ago. Trino started as a full-time feeder, and with training, picked up the responsibility quickly.

“To have a feeder like that – we’re very lucky, because if that’s not done right then nothing goes right. We trained this guy, and he picked it up. He’s organized, he’s quick, he’s clean and he gets the job done.”

Part of Trino’s feed ration still includes brewery yeast water. “In Portland, there are a couple of breweries, and we get the yeast water from them. It provides another source of protein. We grind all of our grain, so we buy whole grains directly from farmers.

We’ll run it through a hammer-mill grain grinder and then add the yeast on top of there while pre-mixing, which gets the bits of grain to stick to the forages – Jerseys are experts at sorting feed to get to the grain – so this way we can deter them from that,” Kircher explains.

Since brewery yeast was the product that introduced Kircher to the dairy industry, it’s only fitting that it be a part of the operation today. PD

-

Lynn Jaynes

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Lynn Jaynes

.jpg?t=1687979285&width=640)