On a recent Sunday, I was listening to a Packers game on the radio while driving home from a family wedding. The radio feed was from the local Green Bay broadcast and included local commercials that are not usually broadcast on national coverage. One of the commercials that aired was from the Wisconsin Corn Growers Association and related specifically to ethanol and its impacts on feed prices.

The ad from the corn growers was focused on convincing the listener that the use of corn for ethanol did not remove corn from the livestock industry for use as feed. I suspect that the majority of dairy producers would disagree with that analysis.

The corn growers’ commercial explained that ethanol production returned distillers grain from the refinery to the livestock industry, and while unstated, it also suggested that distillers grain was an equal substitute for the use of corn by livestock growers.

Distillers grain, although valuable in feeding of dairy cows, is an imperfect substitute for corn. Each bushel of corn used in the production of ethanol represents corn that is not available to the dairy producer for feeding to the herd.

What this commercial represents is the real tension between different segments of agriculture on a critical matter of national policy: Should the U.S. encourage the production of alternative fuels from raw products traditionally used in the food chain?

The answer to the question from any individual farmer or farm organization is predictably influenced by the economic benefits or detriments of producing alternative fuels.

From the aspect of the grain producer, the increased demand for ethanol has resulted in a significant economic boon. The combination of rising land values and increased grain prices correlates very closely with the production of ethanol.

From even a rudimentary economic perspective, it follows that increased demand results in higher prices for the commodity in demand. Conversely, the livestock industry sees the other side of these increased grain prices as the cost of production rises.

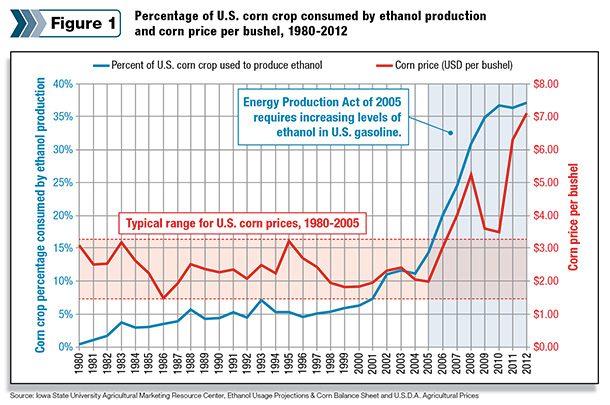

The following chart ( Figure 1 ) illustrates the cost of corn and the increased demand for ethanol.

These increased grain prices have driven the cost of producing milk to unsustainable levels. That is all too well-known among dairy farmers. Much of the economic hardship experienced by dairy producers over the past two years can be attributed to these high costs rather than low prices.

Over the past several months, I have spoken to several farmers who have related that, “We have a cost of production problem, not a milk price problem,” or “I would never have imagined that it would be difficult to be profitable with $19 milk.”

I think those same producers understand that the drought of 2012, which reduced the supply of corn and other grains to the market, had a substantial influence on the price of their feeds, and the changing global demands for grain also shifted the market for grain in a manner that raised prices.

Those producers also recognize that as available corn is diverted to ethanol production, those upward pricing pressures are further exacerbated.

What I also hear from producers is a growing frustration with ethanol production that I do not see directed toward the other economic factors affecting grain prices. I surmise that the reason for these attitudes is that, unlike drought and global demand, the demand for ethanol is not perceived to be a genuine market demand.

Droughts happen, and farmers of all stripes learn to cope and respond. Similarly, markets change and either increase or decrease the demand for farm products.

The market for ethanol is perceived quite differently. Rather than representing the natural and logical outgrowth of market and external forces, the use of corn for ethanol is perceived, almost exclusively, as a function of government policy.

Production and blending credits paid to ethanol producers and distillers, coupled with a government-mandated demand for ethanol, form the basis of a renewable fuel standard.

In August, The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced its 2013 standards for the quantity of ethanol required to be blended into the U.S. fuel supply. And here is the problem for this year: American consumers are not buying enough gasoline to suck up all of the ethanol that Congress and the EPA are scheduled to require.

Americans are consuming less gasoline and, in most cases, blending more than 10 percent of ethanol in gasoline poses problems in distribution and consumption. So what we have, in essence, is a governmental mandate that the unregulated market would not, in all likelihood, replicate and cannot be supported by the market in any event.

To the livestock producer, this must be maddening as the costs of feed continue to represent a bigger percentage of income than they did historically. It is true that the market prices for corn, soybeans and hay have been trending downward in recent months.

September corn prices reached their lowest levels since March 2011. But it is equally true that grains had been trending upward for nearly five years, and the June 2013 corn price was about 250 percent higher than the June 2006 corn price.

As a percentage of the national all-milk price, in June 2006, one bushel of corn was about 17 percent the value of one hundredweight (cwt) of milk. In June 2013, that percentage was nearly 36 percent.

What must be recognized is that what represents a financial albatross for the dairy farmer appears a great benefit to the grain farmer. For the farmer who dairies and also raises grain crops (especially the farmer who grows enough grain above the needs of his herd), the sword is truly double-edged.

And so on the policy front there are livestock groups pitted against corn growers in an attempt to influence decision-makers on what is best for national policy.

Those groups representing “agriculture” in general find their membership in conflict, and I suspect there are even some dairy cooperatives with a substantial portion of their members benefiting from national ethanol policy that are less vocal on the issue than might be expected.

From the perspective of the farm that produces only milk, it is difficult to see how the government endorsement and promotion of corn-based ethanol could be anything but a detriment to that farm’s financial strength.

But as the dairy community continues to react to current policy and seeks to shape policy going forward, it must recognize that the landscape includes more than a few “winners” in the ethanol story whose positions should not be discounted.

And while there may be legitimate disagreements over whether the costs to livestock producers are outweighed by the benefits to other farmers or to the general public, I am reminded of a lesson I learned early on when analyzing farm policy – once a government program results in a tangible benefit to an affected group (which is different from a government benefit program, I might add), alterations to that program that would reduce those benefits in an way are most difficult to adopt. PD

Ryan Miltner is an attorney with Miltner Law Firm LLC.

Ryan Miltner

Attorney

The Miltner Law Firm LLC