Last year, the world dairy market came back strong. U.S. suppliers enjoyed record export volumes, continuing a long-term trend that’s added up to 14 percent compound annual growth since 2003. The importance of the export market to the health of the U.S. dairy industry is undeniable; one of every eight tankers of milk that rolls out of your driveway is turned into a dairy product that’s consumed overseas. When I travel around the world, customers from Guadalajara to Guangzhou tell me they want to buy from the United States. I travel around America’s farm country and most folks here “get it” too.

But farmers always ask tough questions. Here are some of the inquiries I’ve received lately. Maybe you’re having the same discussions at the coffee shop as well.

Export growth sounds great, but how does that help me and my farm?

Exports enable the entire U.S. dairy industry to grow. The domestic market grows 1 to 2 percent per year.

We can meet that with gains in productivity on the farm. So if farmers want to expand – to add cows or bring the next generation into the business – there have to be markets for that additional milk.

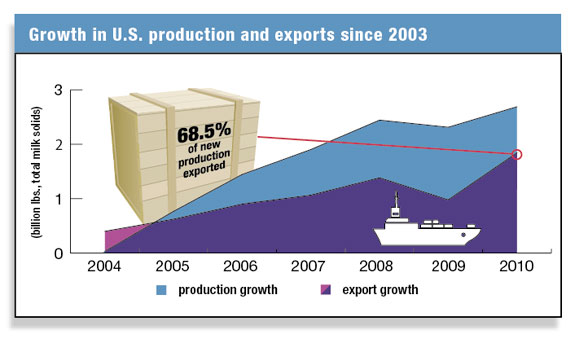

The overseas market has billions of potential customers. Since 2003, U.S. milk production has increased 13 percent, and more than two-thirds of the incremental supply has been sold overseas, according to analysis by the U.S. Dairy Export Council and National Milk Producers Federation. (See chart on page 22).

Why should U.S. producers pursue world markets when global dairy commodity prices historically lag behind U.S. prices?

The perception that overseas consumers can’t afford Western products at Western prices hasn’t been true in years. During the 2007-2010 period, world commodity prices were roughly double what they were from 2001-2006.

As a result, benchmark world prices have been, on average, 15 to 20 percent higher than U.S. commodity prices over the last four years. Exports can and do provide a profitable outlet for a growing U.S. milk supply.

How can we compete with low-cost suppliers?

Demand is outstripping the capacity of the lowest-cost suppliers. Therefore, dairy prices have increased to cover the costs of other suppliers needed to satisfy demand, such as the United States. We have a “low enough” cost of production to be in a position to capture more of this growing demand.

In addition, the United States has a relatively low marginal cost of increased milk production (compared with, say, New Zealand, which will lose its low-cost advantage if it seeks to escape its limits on available land by moving beyond its traditional pasture system to mixed rations).

Isn’t recent export growth mostly attributable to the weak dollar, which is out of our control?

The U.S. dollar’s relative strength is an important factor, but our analysis shows that actual dairy product prices – driven by underlying supply and demand factors – are far more important.

It’s true that the dollar strength/weakness is a major factor when comparing two-way trade between direct competitors, such as the United States and the EU. But in trade between third countries, its impact is felt more in affecting the purchasing power for almost all imported dairy products and does not give U.S. suppliers a competitive advantage.

That’s because dairy trade is done in U.S. dollars, so a weaker U.S. dollar makes all dairy imports relatively less expensive to the importing country, and a stronger U.S. dollar makes all dairy imports relatively more expensive.

The U.S. market is bigger and more secure – why do we even have to bother with exports?

Of course, the domestic market is our most important market, and probably always will be. But doing nothing, maintaining the status quo or ignoring the consequences of globalization will erode our competitiveness. Dairy is a global business that competes with other foods and beverages and with other supply sources for share of stomach.

Therefore, failure to develop a customer-focused competitive advantage leaves the U.S. dairy industry lagging in innovation, exposes the internal market to more imports and encourages more ingredient substitution by food manufacturers.

But if we ramp up production to serve export markets, aren’t we more vulnerable to boom-and- bust cycles, like what happened in 2007-2009 when our exports slowed?

Exporting more or less would not have prevented the wide price swings we’ve endured the last four years. The U.S. dairy business is already exposed to global forces as a result of long-term trends in motion for decades.

Changes in technology, logistics, living standards and dietary habits have altered the market dynamics for dairy worldwide.

In addition, government support programs in the United States and Europe historically had a mitigating effect on volatility. Use of those measures peaked in the 1980s and has been significantly reduced ever since, making global dairy markets more susceptible to shocks like weather, the economy and shifts in policy.

So you’re saying we’re stuck in this boom-bust cycle?

Volatility is probably here to stay, but addressing some of our industry practices in this context can help us cope and even thrive. The painful crash that U.S. dairy farmers endured in 2009 is partly a function of the U.S. being a supplier of last resort on the world market.

Our existing dairy policies, price support in particular, make us the first out and the last in when market conditions turn, and that makes us especially vulnerable.

Becoming a more consistent supplier by closer attention to customer needs and a more diverse product mix, especially in various dairy proteins, will reduce the dramatic cycling in and out of the international market that contributes to the periodic misalignment of supply and demand in our home market.

Some of the programs the industry is addressing are: improving use of risk management tools, enhancing our quality and traceability systems and developing a product portfolio that better meets buyer requirements.

Industry organizations also are looking at modifications to our milk and commodity pricing systems and safety nets that currently act as a disincentive to making the products global buyers want. PD

Tom Suber

President

U.S. Dairy

Export Council

info@usdec.org