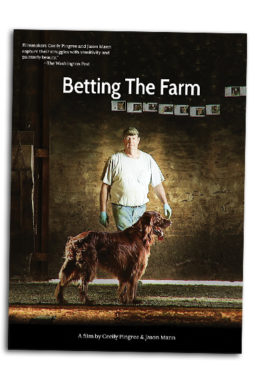

Watching a new documentary about the 2009 plight of a group of Maine dairy farmers was like eating a Tootsie Pop –I kept counting how many licks it would take before getting into the best part of it. "Betting the Farm" details the struggles of fluid milk processing co-op MOO Milk, short for Maine's Own Organic Milk. I saw the movie mentioned on a few blogs after its release earlier this year.

I ordered a copy of the movie online ($15, no shipping charge), but it's taken me some time to finally watch it. After one of our magazine columnists mentioned the movie in a recent issue, I thought I should finally watch it.

So in true movie-watching style, I munched on popcorn and sipped a Pepsi for the full 84-minute flick. No actual lollypops were consumed, or harmed, in the preparations for this review.

The movie explains how several dairy farm families lost their milk hauling contracts during 2009. Most of them are 600 miles away from the nearest Northeastern processing facility.

Click here to read author Kirk Kardashian's thoughts on this documentary.

So they decided they would process their milk and sell it as cartoned gallons themselves. They hired a CEO who promised them they could milk their cows while he set up and funded their co-op business.

Having been in several modern, commercially owned milk processing plants in the U.S. and abroad, I could quickly tell just how small-scale the co-op's processing operation was.

This was not more evident than when the CEO of the co-op, dressed in his jeans and sport jacket, sits on a milk crate and performs his own "drop test" to determine why the co-op's milk cartons were breaking open on the bottom and leaking, which was an obvious frustration to store owners stocking the co-op's milk in their dairy cases.

One of the most interesting lessons from the movie for any producer-handler is that you shouldn't honestly believe that if you milk it, people will automatically just buy it.

As one of the dairy farmers in the movie succinctly said, "It's not like you have a new product. You have milk. If yours ain't there, they buy someone else's, and you hope that people like yours better."

This past year, I had my own experience capturing what it's like for a producer-handler as I interviewed Todd Moore.

He reiterated the same thing the movie characters did and said milking his cows was the easiest part of his value-added business.

Getting the product to the consumer, securing shelf space and ensuring the freshness of the product that the store had stocked on its shelves were the hardest elements of being a producer-handler, he said.

In my opinion, the movie captured these challenges well. However, I was disappointed that the editing of the film made it appear that a dairy farming lifestyle is slow-paced with lots of time for reflection and monologues.

Most farmers I've met and interviewed are much more active. I would guess the movie's characters are too. I believe the filmmakers just didn't capture it.

However, they did accurately portray the emotions and wrenching decisions of a family who is dairying. The dairy farmer characters' elation at the offer of $30 per hundredweight (cwt) for their milk when the movie begins quickly subsides as they realize their management's challenges in securing a steady stream of weekly milk buyers.

About 3,500 customers, the co-op claims, would have to buy one gallon of milk per week in order to support their promised pay price. They never reached that goal throughout the movie.

The movie bounces back to a more upbeat note at the end, as the characters temper expectations about their co-op's producer pay price potential and the immediacy of the new brand's growth opportunities.

It seems betting the farm is still a long-term market position with a lot of short-term headaches. PD

Walt Cooley

Editor

Progressive Dairyman magazine