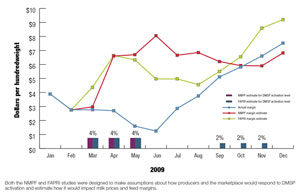

Though dairy producers would like to forget 2009, it’s still the center of attention when talking about reforming dairy policy. The severity of depressed milk prices and feed margins in 2009 makes it the extreme case study to test just how intrusive a proposed supply management program would be for U.S. producers. Since the beginning of the year, three different reports have been released analyzing the effect of the Dairy Market Stabilization Program (DMSP) on producers in 2009. DMSP would establish a temporary milk production base when the margin between milk price and feed cost narrows. Click here or on the image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

The base would kick in when the price of milk minus feed cost is less than $6 for two consecutive months. The program is included in National Milk Producer Federation’s proposal for dairy reform and is opposed by the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA).

The chart at right and the analysis that follows attempts to explain the differences between the three published studies. Click here or on the image to view it at full size in a new window.

The studies are identified throughout the remainder of this article as the Informa study, published in January by the agribusiness consulting firm Informa Economics and funded by IDFA, with Informa economist Nate Donnay as project leader; the NMPF study, published in March and designed by Peter Vitaliano, an NMPF staff economist; and the FAPRI study, published in March and completed by economist Scott Brown of the University of Missouri’s Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute.

Types of economic analysis

The Informa study is the most different of the three DMSP studies published this year. It does not attempt to estimate how milk prices or milk-feed margins would have changed under the proposed guidelines for DMSP implementation.

Instead, the study aimed to quantify the total value of milk production that producers may not have received if DMSP was activated. The report calls out the difference between the historical milk production value and value producers would have received minus DMSP withholdings.

“What we wanted to avoid with our study is arguments about model design and assumptions,” Donnay says.

Both the NMPF and FAPRI studies were designed to make assumptions about how producers and the marketplace would respond to DMSP activation and estimate how it would impact milk prices and feed margins.

“Our models are certainly similar but not identical,” Brown says of his study and the NMPF study.

Duration of the program’s effect

A consistent difference among all of the published studies is the estimated duration of DMSP activation. In general, DMSP would be activated if the difference between milk price and feed cost was below $6 for two consecutive months. This would trigger the calculation of a producer’s base (either a three-month rolling average or a year-over-year change).

Milk marketings would be paid at 98 percent of the producer’s base or 94 percent of current marketings, whichever is greater. In 2009, the milk price-feed cost margin was below $6 for nine months of the year, by far the longest consecutive period of below-$6 margins in the past decade.

The Informa study shortened the estimated activation period for DMSP by 30 percent to six months, anticipating some level of producer response in the face of overbase marketings. However, the study did not estimate how this producer response would have changed milk prices or feed cost margins from month to month in 2009.

The remainder of the Informa study’s evaluation method has little in common with the NMPF and FAPRI studies.

Calculating overbase marketings

The FAPRI study assumed that 50 percent of all producers (24 aggregated state milk-production averages each representing a “producer”) in its model would reduce overbase milk marketings for as long as DMSP was active.

The NMPF study’s model treated all producers as the average U.S. dairy farm, both in milk production and herd size, and categorized overbase producers into one of three segments during the 2009 DMSP activation period – reducing milk production, remaining the same and increasing milk production.

Vitaliano says most producers in his model were either reducing production or maintaining it. He estimated only a few would expand production during a DMSP activation period.

He says California’s co-op-imposed milk marketing caps or “quotas” are a good reference point for how producers respond to an overbase situation. The response in milk production, he says, is significant and rapid.

“Producers do pretty quickly realize what the new rules are and adjust to them,” Vitaliano says.

Because the 2009 low margin period began in January and persisted through the spring, Vitaliano says his model shows at least 50 percent of producers cutting back overbase production and as many as 70 percent during that time period.

“I saw there was a fairly substantial cost for not complying,” Vitaliano says. “My analysis showed there would be a high level of producers complying, which showed up pretty quickly as an increase in margin.”

Buying cheese and its impact on price

Under DMSP, overbase milk marketing value is collected and spent to purchase cheese from the market and donate it to food banks or other noncommercial uses. Both the NMPF and FAPRI studies attempted to estimate how this would impact milk prices and duration of DMSP implementation.

Both programs estimated that cheese purchases would remove the annual milk production equivalent of more than 35,000 cows. Scott Brown says his model assumed inelastic demand for dairy products, meaning when there is a change in the amount of supply, there is a more significant change in price. FAPRI’s analysis showed that for every dollar spent on cheese purchases, producers returned $3 in value.

“Consumers don’t substitute away from dairy products very easily,” Brown says. “I say this because many people probably don’t realize that demand might be causing more of what we see in this analysis than the actual implementation of the program may be causing.”

Brown says his stricter inelastic demand is the same reason why his study’s margins may have narrowed more quickly in the summer of 2009, causing DMSP to reactivate.

On the other hand, Vitaliano says his model showed the impact from the demand side would lag compared to producers’ response to reduce supply. He calls DMSP’s total package robust and flexible.

“If producers react to DMSP implementation by substantially cutting back their marketings, there will be relatively few collections, but a significant impact on supply,” he says. “However, if producers continue to market and do not react on the supply side, there will be a substantial amount of milk for which payment is redirected to the purchase of non-commercial cheese donations. That will have a huge effect.”

Vitaliano says most producers understand the basic concepts of NMPF’s dairy reform.

“There are many producers for whom this is a key piece of dairy reform,” he says.

Brown advised producers to look beyond DMSP’s role in milk pricing in 2009 to thoroughly evaluate the program.

“I like to remind people that 2009 was an extremely difficult time for the dairy industry,” Brown says. “I’m not of the belief that we will find many times ahead of us in which we will experience the kinds of low margins that we experienced in 2009.” PD

-

Walt Cooley

- Editor

- Email Walt Cooley