The loss of Alaska’s state-subsidized Matanuska Maid dairy at the end of 2007 devastated milk producers in the fertile Matanuska Valley, long the agricultural heart of Alaska. Now, more than three years later, the state’s milk production has recovered from a low of 2009 – when Alaska milk production dropped 17 percent – to rebound at the end of last year.

And 2011 first-quarter USDA stats indicate Alaska milk production is up some 20 percent. What gives? USDA statistics show an increase from 1.5 million pounds of milk produced in Alaska the first quarter of 2010 to 1.8 million pounds the first quarter of this year. The Matanuska Creamery in Wasilla can take much of the credit for that upswing, although the plight of the dairy farmers is still far from over.

Karen Olsen, CEO of the Matanuska Creamery in Wasilla, feels the pulse of dairy production in the Matanuska Valley.

“We’re still trying to bring more production on line. We’ve never really hit our optimum production, which is 1,800 gallons a day. But we have come up from what it was in late 2007 and early 2008.”

Olsen says the creamery has helped to fill the gap left after the state’s last fluid processor Mat Maid went out of business. That demise was blamed on an out-of-date business model, which relied on imported milk from out of state to meet retail demand.

But when Mat Maid went down, so did the processing equipment local producers needed for homogenization and pasteurization. The Matanuska Creamery stepped in to buy dairy product, but it was a long winter’s wait before the creamery came on line. Olsen says some of the local producers never recovered.

“It’s been a struggle since the farmers have been hit so hard by the loss of about six months worth of milk when Matanuska Maid went out, and they’ve lost a lot of, I guess, confidence in the future of agriculture in this state.”

The creamery produces aged cheddar, cheese curds and ice cream, but its mainstay item is milk, in gallons and half gallons, and it now furnishes half pints for the Matanuska Susitna Borough school district.

The creamery provides the school district 500 gallons of milk a day, Olsen says. The rest of the milk goes to retail sales. Olsen rues the fact that retail outlets could use about 3,000 gallons more milk a week.

“So there is definitely room to grow,” she says.

What’s needed now is a few more cows to boost production, Olsen says, because the creamery is struggling with less milk than it needs to break even for about seven months out of the year. The creamery hits the breakeven figure of 1,800 gallons a day only in summer months.

“I think that since we have been able to outsell our production this past winter, we’ll be able to attract a few more cows and get production up a little bit further. There is a good background of desire for local product ... that’s the key.”

Despite Olsen’s dismay at the dearth of Alaskan cows in production, the cows seem to be producing more milk.

Alaska milk production has shot up since the end of 2009. And stats for the first quarter of 2011 indicate a 20 percent jump over the first quarter of 2010.

Even the amount of milk produced by individual dairy cows in the state is up, according to federal statistics released in February.

What’s the reason for the increase? “That one’s easy,” says Lois Lintelman, who with her husband, Don Lintelman, runs the Northern Lights Dairy, a producer-handler near Delta Junction, Alaska.

“We had lots of heifers come into milk. They started calving in January,” they say.

She says they are currently milking 60 cows.

Conversely, Lois says, in October of last year, Northern Lights Dairy stopped bringing in milk from out of state to process, due to high freight prices.

Even though Northern Lights is gaining in milk production, Lois Lintelman says the dairy has had to cut back on supplying as many stores as it had before it stopped importing milk from out of state.

The Lintelmans are one of two dairy farmers in Alaska’s interior region near Fairbanks, Alaska’s second-largest city. Northern Lights is the last remaining dairy in the state’s interior. Twenty or so years ago, there were two.

Over at the Matanuska Creamery, Karen Olsen says milk production could be up because local markets opening up for milk helps farmers buy more feed, which in turn fosters more milk per cow.

But she cautions that any giddiness about tiny increases in milk production this year should be measured against the 33 million pounds of milk produced in the Matanuska Valley area during the later 1980s, when the state took over management of Mat Maid. Dairy farmers near Delta Junction produced another 3 to 4 million pounds in those years.

Now both areas are dramatically down in production, Olsen says. Alaska dairy farms supported five or six times the volume of milk they do now, when the state’s population was much smaller.

When the state of Alaska abruptly shut down the Mat Maid Dairy in December of 2007, the local dairy industry took such a hit that it is still reeling. Olsen says the creamery was set up quickly, to shorten the time the dairymen were forced to dump milk, and that there are still problems playing out from that desperate time.

“The industry has still not adjusted to producing for a real local market where they [the local dairy farmers] are the only suppliers. The creamery needs more milk to process and a more even milk supply.”

The creamery has state commercial loans, but no subsidy. A federal grant was used to start the creamery in 2008. The dairy farmers own stock in the creamery and have recently formed a cooperative within the creamery.

“If there had been any profits, they [the farmers] would have participated in them,” Olsen says.

She says the creamery pays the farmers a rate that was set when the federal grant came through, but she says the creamery is behind in its payments to the farmers and is now looking to lower overhead by finding a building with a more affordable lease.

“We are awaiting the summer grazing season to bring a spike in both calving and milk production. Then we should be satisfying local retail demand and selling well at farmers markets,” Olsen says.

That plan should boost revenues. But she says the milk supply has to come up too, and that means more cows.

Tell that to Wayne Brost, a Matanuska Valley dairy farmer who has weathered the ups and downs of Alaska’s dairy industry since the mid-90s. He says the creamery buys his milk now, but the future of dairy farming in Alaska looks pretty bleak.

“We are dinosaurs,” he says of his dairying colleagues.

“I’ve been out here dairying since 1995,” he says from his rambling log home in Point MacKenzie. “We don’t use any hormones, we use a grass-based forage which in turn gives you healthier omega-3 fatty acids in the milk.”

“It’s fresher by far, of course,” he says, quoting the old Mat Maid slogan, “and we use a low-heat pasteurization.”

Brost says, despite the creamery’s help, it’s getting harder and harder to produce milk and make ends meet.

The winter of 2007-2008, Brost, like other dairy farmers in the area, faced the possibility of slaughtering his herd because there was no place to sell milk. Now, Brost’s farm is one of three that provide milk for the creamery, but he says cost increases on his end have leveled any boost in income.

Brost can reel off the numbers ... fertilizer has jumped from $160 a ton to $700 a ton since he began dairying ... but the price farmers get for the milk product stays the same.

“I guess we’d have to get more money for our product. In light of the spiraling input costs, everything goes up but our end product stays the same. That doesn’t compute – that doesn’t work. The producers have to have more for their product, or they’re not going to stay liquid. That’s it.”

Brost says costs in Alaska make it more expensive to run a dairy farm in the state as opposed to say, California. And, Brost says, the creamery’s debt load prevents the creamery from paying dairy producers more for their fresh milk.

Brost and his wife have no health insurance, and they raise much of what they eat.

“I’m cooking a moose roast on a wood stove as we speak,” he said. And he worries that in six months he may have to quit dairying.

“I’m subsidizing this deal out here [his farm], and I’m not going to do it much longer. I’m not a wealthy man, so I can’t do it.”

Brost faults the state for not doing more to help agriculture. He says there were 40 dairy farms in Alaska 20 years ago. Now only three operate in the Matanuska Valley.

Olsen, as opposed to Brost, says there’s room for expansion. She says the creamery runs in the red when there is less milk available, so she sees growth as the answer. And she worries that the loss of one dairy farmer a couple of months ago has pushed Alaska’s dairy industry into a “grow or die” position.

“We needed about 40 or 50 more cows than we have in order to keep all the shelves in both Anchorage and the [Matanuska ] Valley full during the winter. We won’t have any trouble at all this summer, but we’re encouraging the farmers and prospective farmers to think about a few more cows for the wintertime.”

Brost says there’s no question that there is a market for the milk, and that what is needed is more production, but at this point, it is unlikely dairying will attract newcomers.

“Look,” he says, “there’s five of us dairying out of 710,000 Alaskans. What does that tell you?” PD

PHOTOS

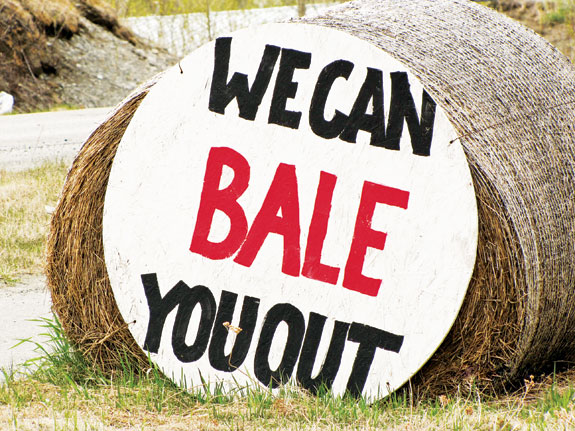

The Matanuska Creamery is struggling with less milk than it needs to break even for about seven months out of the year. Photos by Fidencio Romero.