According to the paper written by Dr. Amy Hazel, Dr. Brad Heins and Dr. Les Hansen at the University of Minnesota, daily profit was 13% higher for the two-breed crossbreds (Viking Red × Holstein and Montbeliarde × Holstein) and 9% higher for the three-breed crossbreds (Holstein, Viking Red and Montbeliarde) than their Holstein herdmates.

This extensive study, initiated in 2008 and continued through 2017, included seven Minnesota herds. It started with at least 250 foundation Holstein females in each herd. As researchers strategically mated these animals, a portion were selected to continue to produce Holstein descendants, while the others would produce ProCROSS offspring in the generations that followed. (Note: The ProCROSS is a planned rotation of the Holstein, Montbeliarde and Viking Red breeds.) The goal of the study was to compare the profitability of crossbreds and their Holstein herdmates with special interest in differences for health treatment costs and other input costs.

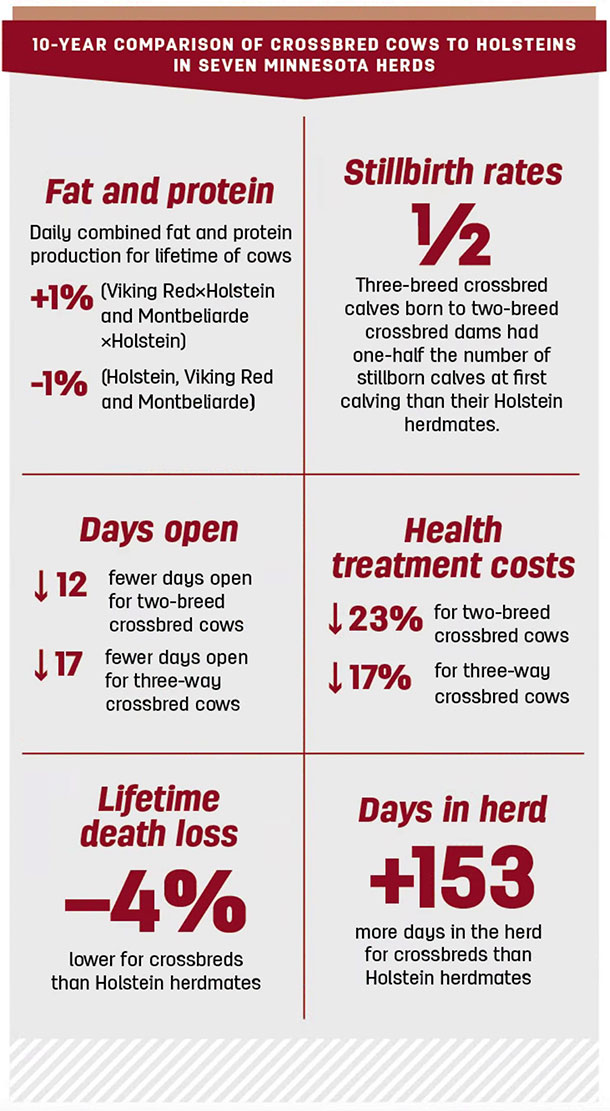

Key findings from the study include the following:

-

Fat and protein: Daily combined fat and protein production for lifetimes of cows was 1% higher for two-breed crossbreds (Viking Red × Holstein and Montbeliarde × Holstein) and was 1% lower for three-breed crossbreds than their Holstein herdmates.

-

Stillbirth rates: All generations of the crossbred cows had lower stillbirth rates, and the three-breed crossbred calves born to two-breed crossbred dams had one-half the number of stillborn calves at first calving than their Holstein herdmates.

-

Days open: The two-breed crossbreds had 12 fewer days open, and the three-breed crossbreds had 17 fewer days open than their Holstein herdmates.

-

Treatments: Health treatment cost was 23% lower for the two-breed crossbreds and 17% lower for three-breed crossbreds than their Holstein herdmates.

-

Death loss: Lifetime death loss was 4% lower for both the two-breed crossbreds and the three-breed crossbreds than their Holstein herdmates.

- Replacement costs: The combined two-breed and three-breed crossbreds had 153 more days in the herd than their Holstein herdmates. Therefore, replacement cost was substantially lower for both the two-breed and three-breed crossbreds than their Holstein herdmates.

What the expert says

As the researcher leading this decade-long study, Hansen himself says he was surprised by some of the stones turned over while digging through 10 years of data from the seven Minnesota herds. Among them, the profit potential itself.

“The spectacular results for the profitability of Montbeliarde crossbreds compared to their Holstein herdmates were a bit of a surprise,” Hansen says, pointing out he anticipated the favorable results seen with the Viking Red breed, which is based mostly on the Ayrshire.

He was also pleased with the milk components comparison. Though earlier results from a California study suggested these crossbred cows may have about 2% lower production of milk solids, the results of this study indicated no loss of fat (kilograms) plus protein (kilograms) production across generations for the crossbreds compared to their Holstein herdmates.

The health advantages resulting from hybrid vigor served to sweeten the pot. “The huge advantage of the [crossbred] cows over their Holstein herdmates for reduced health treatment cost was even larger than we would have anticipated,” Hansen says. “Perhaps that is why all other farm animals have taken advantage of crossbreeding for commercial production for more than 30 years.”

Mike Osmundson, founder of California-based Creative Genetics, an A.I. company, sees additional noteworthy points within the data. A little more than 20 years ago, he recognized developing concerns among local dairy producers with their purebred cattle and introduced the strategic mating of Holstein, Viking Red and Montbeliarde to a handful of dairies. Since then, he’s observed improvements in profitability of many of these herds, in part due to the vigor and health of calves from day one, that carries on into adulthood.

“Because of the crossbreeding, many more things were improved than expected, such as: More calves born alive, more calves still alive per 100 born after 60 days of age, greatly improved body condition, reduced dry matter intake among growing heifers with cheaper feedstuffs and less incidents of pneumonia,” Osmundson says. “After entering the milking herd, we noticed stronger cows with better body conditions, higher pregnancy rates and less sick days spent in the hospital.”

A way around inbreeding

Beyond production and performance, both Hansen and Osmundson see a bigger picture for how crossbreeding could shift the genetic potential of the national dairy cattle population by eliminating the potential for inbreeding depression that is experienced within purebred animals.

With the average inbreeding coefficient among U.S. Holstein females born in 2019 over 8% – and continuing to climb year-over-year – Hansen believes the crossbred sire stack is a way around the potentially detrimental effects of pedigrees with common parentage.

“Crossbreeding eliminates concern about inbreeding depression and, instead, provides for enhanced performance and profitability due to hybrid vigor,” he explains. “Commercial pig, beef cattle, chicken and turkey producers all fully embrace hybrid vigor to enhance the profitability of commercial animal production.”

What is the driver behind the inbreeding dilemma? Hansen points a finger at the rapid reduction in pedigree variety since the onset of genomic selection over the past decade. He adds, “The average inbreeding into the future of pure Holstein and pure Jersey matings will be extremely high. It will be critical for dairy producers who wish to remain with pure Holstein or Jersey herds of cows to carefully match bulls with individual cows and heifers to avoid extraordinary high doses of inbreeding in individual matings.”

Osmundson reiterates those concerns, noting, “In the future, inbreeding will ruin some breeds if certain precautions are not taken to slow the rate of inbreeding depression.” He predicts crossbreeding will become the norm; however, he believes the most successful results will only be possible with a deliberate strategy.

“Some crossbreeding of dairy cows has been based on hearsay, half-truths and fantasies, and that has failed miserably,” Osmundson says. “A good crossbreeding program needs three unrelated breeds that complement each other in the rotation to maximize the hybrid vigor at its highest level possible.”

The future of crossbreeding

Osmundson believes these results from “real dairies with real facts,” published by a scientific, peer-reviewed journal, will provide dairy farmers with valid information for making major herd decisions that may be out of the norm from what they have chosen in the past.

“Today’s dairymen have to make great decisions based on facts, not emotions toward a certain breed of cows or a certain comfort,” Osmundson says, adding it’s no longer about the breed that “got us here.”

Hansen further notes the adoption of crossbreeding on a global scale. He adds, “A very large number of dairy producers around the world have moved to crossbreeding programs for the cows in their dairies.”

It is feedback and questions from dairy producers that drives continued crossbreeding research at the University of Minnesota. A current project compares how the ProCROSS and Holstein cows in the campus dairy herd respond to two alternative rations: One ration is a traditional Midwestern TMR based on corn silage; the other is a TMR with higher fiber but lower starch. Hansen explains, “The justification for this current study is: Many dairy producers who are milking ProCROSS cows believe [they] may outperform Holstein cows to an even greater extent if they are provided a TMR with more fiber and less starch.”

With 10 years of sound science under its belt, the three-way crossbred cow is proving its economic value in real dairy herds, opening the barn doors wide open for where this strategic breeding program may go from here. ![]()

-

Peggy Coffeen

- Editor

- Progressive Dairy

- Email Peggy Coffeen