CompaniesNeogen – Pat Frasco, Director of Milling and GrainLallemand Animal Nutrition – Tony Hall, Technical Services – RuminantBiomin America Inc. – Paige Gott, Ruminant Technical ManagerAlltech – Max Hawkins, Alltech Mycotoxin Management Nutritionist

1. What mycotoxin trends did you observe in 2017, and which strains were more prevalent?

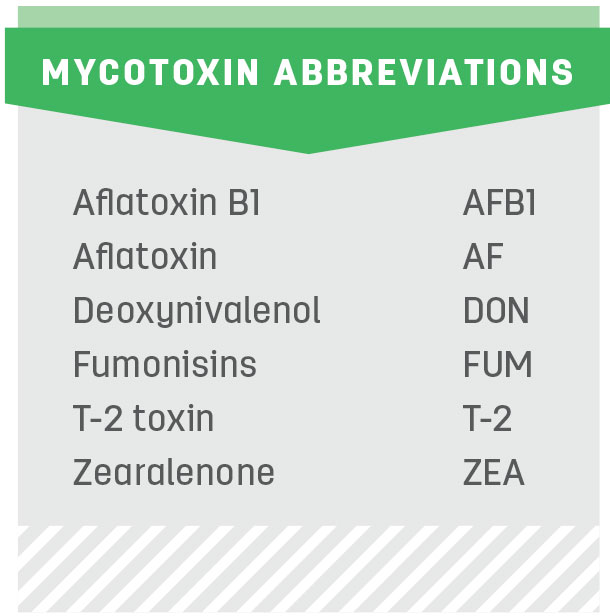

Frasco: The 2017 U.S. growing season, with its record rainfalls and persistent areas of drought, will go down as one of the oddest in history. All things considered, 2017 was a fairly normal year for mycotoxin production, with pockets of vomitoxin or deoxynivalenol (DON) reported in wheat and barley, and numerous isolated reports of aflatoxin (AF), DON and other mycotoxins mainly in corn, corn silage and corn-feed products.

Hall: The vast majority of samples observed by Lallemand were corn silage, high-moisture shell corn, earlage, snaplage and dry shelled corn samples. The ensiled corn products were often contaminated with spoilage yeasts and molds.

The most prevalent mycotoxin observed this year was DON, followed by zearalenone (ZEA) and fumonisins (FUM). The ZEA and FUM results were much less prevalent than DON but still very important to note. T-2 toxin was occasionally detected, especially when moisture was variable throughout the growth stages and again at harvest. These mycotoxins are all derived Fusarium mold species and were likely formed on the crops while standing in the field.

Gott: Our corn survey included corn grain, fermented feeds and corn byproducts. The type B trichothecenes (family that includes DON) have been the most frequently detected mycotoxin group in our survey since 2014. This holds true again in 2017, with 75 percent of the samples testing positive for type B trichothecenes. FUM and ZEA were also prevalent in our 2017 survey.

The prevalence of all three mycotoxin groups is back to what was seen in the 2015 harvest. Similarly, co-occurrence, or the presence of more than one mycotoxin at 47 percent, is back to 2015 levels.

Hawkins: The 2017 crop showed higher levels DON, FUM, ZEA and Penicillium than the previous two years. Samples with aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) were more prevalent at harvest.

2. What mycotoxin levels did you see in grain and forage samples, and what areas of the country had the most difficulty?

Frasco: Through a combination of working with our mycotoxin testing customers and information from other sources, we received reports of DON in wheat throughout the rain-soaked Gulf and Southern states and the Northern Plains. In corn, corn silage and corn-feed products, we received confirmed reports for a wide variety of toxins found above concern levels.

These reports included AF in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Alabama, Georgia, Iowa and North Dakota; DON in Texas, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Iowa, South Dakota, New York, Wisconsin, Kansas and Nebraska; FUM in Texas, Missouri, North Carolina, Kansas, Alabama, Tennessee, Oklahoma, New York, South Dakota and California; ZEA in New York, Iowa and Mississippi; and T-2/HT-2 in Texas, Wisconsin, New York and South Dakota. Note that, although I mention entire states, growing conditions and mycotoxin production can vary widely within a state.

Hall: It was not unusual to find DON levels in ensiled corn products ranging from 2 parts per million (ppm) up to 12 ppm all across the country. While some of the mycotoxin levels would not always be considered high on their own accord (ZEA less than 0.4 ppm, FUM less than 2 ppm and T-2 less than 0.1 ppm), they should really be evaluated as the “total load” being fed through the TMR.

Gott: The majority of samples in our survey originated from Midwestern states. High levels of type B trichothecenes were more common in Midwestern samples, while higher levels of FUM as well as AF were more prevalent in samples sourced from Southern states. High FUM contamination also extended into several Midwest and Great Plains states. The prevalence of the various mycotoxins is similar to levels seen in 2015, with average contamination levels that can negatively impact the health and productivity of dairy cows and calves.

Hawkins: Corn silage samples had average values for DON, FUM, fusaric acid and Penicillium at 2 ppm, 23.2 ppm, 1 ppm and 0.087 ppm, respectively. AFB1 averaged 0.004 ppm, but the high level was at 0.125 ppm. Corn and high-moisture corn samples averaged 0.983 ppm, 4.1 ppm and 0.088 ppm for DON, FUM and ZEA, respectively. The highest level for DON was at 17.2 ppm and 65.5 ppm for FUM. AFB1 averaged 0.003 ppm with a high value of 0.606 ppm.

3. What conditions influenced the prevalence of mycotoxins this past year?

Frasco: As mentioned, it’s hard to think of a stranger growing season than what we experienced in 2017. August brought two devastating hurricanes, which dumped massive amounts of flood-causing rain on the Gulf States and elevated rainfall levels throughout the South.

And yet drought-like conditions lingered in Iowa and South Dakota. Nationally, temperatures in the first six months of the year were 3.4ºF above the rolling 30-year average; precipitation was 17 percent above average. In June, we had very dry conditions in Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado and the Southern states, and parts of the upper Great Lakes regions experienced above-normal moisture.

July brought dry conditions to the western Corn Belt and the Northern Plains. Temperatures were near normal in most areas, although the plains and western U.S. saw well-above-average temperatures.

Hall: Last season, the eastern U.S. had a wet start to spring, stressing plants during early growth stages, followed by relatively good weather and ending with a lack of moisture through summer. Around harvest, damp weather allowed almost perfect conditions for field-borne mycotoxin production from FUM and Gibberella mold species, along with massive increases in spoilage yeast infestations.

These conditions allowed mycotoxins such as DON, ZEA and FUM to be present and resulted in higher levels than typical in ensiled feeds.

Gott: The main mycotoxin challenges seen in our survey – type B trichothecenes, FUM and ZEA – are mycotoxins produced by various Fusarium molds which are associated with production in the field in the presence of excessive moisture before harvest. Hurricanes during the late growing season are believed to have contributed to high levels of FUM in Southern crops.

Unfortunately, weather conditions are beyond our control, but proper management practices can help reduce stress to the plant and, in turn, may limit mycotoxin production. Proper storage conditions are also important to limit additional mycotoxin production post-harvest.

Hawkins: The risk is the result of a delayed spring planting and wet weather prior to and through harvest. The Southwest had drier weather and then, as harvest approached, the hurricane brought excessive rain. This resulted in extremely high levels of FUM.

4. What advice would you give for 2018 mycotoxin management programs?

Frasco: I encourage grain producers and processors to review their food safety plans on at least an annual basis to judge how their plans assess their risk from mycotoxins. These plans should be specifically tailored to their operations, which vary by region of the country and products handled and produced.

We post weekly reports in our Monday Mycotoxin Crop Report during the growing season and harvest to help awareness of mycotoxins known to be of concern. Another helpful resource is a webinar with Dr. Cassie Jones of Kansas State University that addresses mycotoxin risk management and the Food Safety Modernization Act.

Hall: My checklist for minimizing mycotoxins.

In-field and harvest:

- Plant insect- and disease-resistant hybrids.

- Review tillage practices or crop rotation.

- Harvest at the correct moisture and maturity.

- Be aware mycotoxins may have formed in the field pre-harvest.

- Use a proven combination inoculant containing both homolactic bacteria and L. buchneri at the FDA-reviewed rate.

- Isolate damaged crops (drought, hail, etc.).

- Ensure proper packing and storage to minimize oxygen infiltration into the pile or bunker.

Feedout:

- Avoid excessive air infiltration during feedout.

- Always discard visibly spoiled material.

- Optimize rumen function of animals fed contaminated feed.

- Use a research-proven active dry yeast probiotic along with yeast cell wall products or clay products to combat the compromised rumen function.

Gott: A comprehensive mycotoxin risk management system as outlined should be put in place as a year-round strategy to counter mycotoxins:

- Monitor feed for mycotoxin contamination by analyzing it periodically through commercial laboratories to identify risk levels.

- Adjust the ration and limit mycotoxin exposure in the herd.

- Use an anti-mycotoxin product that serves scientifically proven multi-pronged approach to detoxify the adsorbable, as well as non-adsorbable mycotoxins, while also helping the liver and immune system to recuperate from the negative effects of mycotoxins.

Hawkins: Rotating crops, doing more tillage to incorporate crop residue will certainly help lower risk. Avoid delayed plantings, and control insects as much as possible. In preparing for harvest, continually check plant moisture levels to achieve a more ideal silage for feeding and packing.

Corn grain should be harvested without excessive field exposure and dried to 14 percent moisture. ![]()

-

Audrey Schmitz

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Audrey Schmitz