Corn silage is often the main feed source for dairy production systems. However, annual cool-season forages can be a viable option for merging forage production and nutrient management during the “off season.”

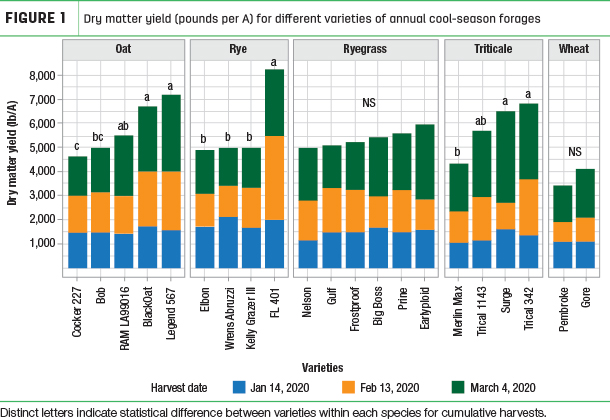

The mild winters and long growing season of the southeastern U.S. offer an opportunity for double (or even triple) cropping, and those winter forages can be a perfect fit to complement forage production and serve as cover crop for land and waste management. Cool-season forages can be highly productive under high fertility and irrigated land (Figure 1 ).

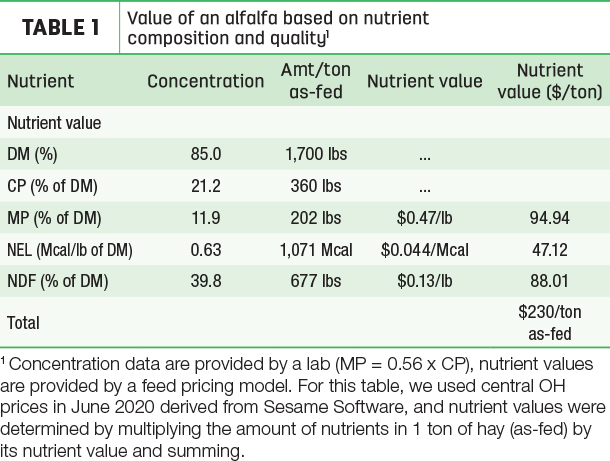

The high-quality forage (Table 1) can be used for greenchop, silage, hay or grazing.

From a nutrient management perspective, managing a crop during the winter means greater nutrient exporting capacity. For example, consider a back-of-the-envelope calculation of an average of 7,000 pounds dry matter per acre production and an average 2.61% nitrogen (16.3% crude protein) and 0.36% phosphorus; this represents 183 pounds nitrogen per acre and 25 pounds phosphorus per acre (or 58 pounds P2O5) exported from the field. Feed-wise, this equates to nearly 9 tons of silage or 4 tons of hay.

What performs best?

What to consider when choosing cool-season species and variety to plant? Although cool-season forages can have excellent performance, given adequate conditions, there can be large performance variations among forage species and varieties. To better address the question, each winter the UF/IFAS Extension forage team develops a variety trial taken to multiple dairies in the region, in order to evaluate both commercial and experimental cool-season forage performance in real dairy production systems. Results from the 2019-20 trial are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Trials were planted at four locations in north Florida, between Nov. 20 and Nov. 22, 2019, and harvested at three dates (Jan. 14, Feb. 13 and March 4, 2020). Small grains (oat, triticale, rye) performed best over a short (about 105 days) season, while all ryegrass varieties put on most of their growth later in the season, particularly by the time of the final harvest. Across species, Legend 567 oat, FL 401 rye and Trical 342 triticale were among the best performers within each of their groups, due to good genetic potential (including disease tolerance) and relatively early maturity. Maturity also reflects on the nutritive value (Table 1), where early maturity cultivars (e.g., Legend 567 oat and FL401 rye) will tend to decline in crude protein, digestibility and increase the fiber content toward flowering stage.

When deciding upon what to plant, begin with varieties known to grow well in your region. Then define your purpose: grazing, greenchop or silage, or hay. Grazing typically relies on a longer season, where a mixture of varieties (i.e., small grains + ryegrass) might be the best choice, whereas for silage, productivity at boot stage might be your criteria. Hay might focus on late season or early season production.

Furthermore, consider timing, where some varieties (regardless of species) are earlier maturing, while others mature later (longer season). This is especially critical when planning for the subsequent summer silage crop. Ryegrass, for example, did not show much difference in production among varieties up to the March harvest. However, it is a later-maturing species compared to some of the early oat and rye varieties. When mixing rye and ryegrass or oat and ryegrass, it is possible to benefit from the early production of the small grains and the longer season of the ryegrass. If planting corn early, like in the Southern Coastal Plain (March-April), then ryegrass might not fit your operation, and early maturity small grains will be a better option.

It is well worth repeating that forage breeding programs focus on developing materials adapted to your location and conditions (productivity, maturity, disease and pest tolerances), so select from what is recommended for your region. Invest in high-quality certified seed, which should ensure you get good germination and performance and will greatly reduce the possibility of importing weed seed and seed-borne pathogens into your fields. The few extra dollars per bag is a good investment. For example, in 2019, a 50-pound bag of Legend 567 oat was averaging about $29, while common Coker 227 oat was about $21. This means a $16 difference per acre on planting costs, but 3,500 pounds dry matter per acre productivity gain with Legend 567.

Notes on harvest and grazing

When used for grazing, avoid grazing too early, before the stand reaches full ground cover and is at least 10-inch canopy height for small grains or 8-inch canopy height for ryegrass. Also, avoid letting small grains start to head (or boot stage) when plant growth shifts from vegetative to reproductive and start producing seeds. Small grains will not recover well after a grazing event if plants are already in the reproductive stage. When grazing, leave at least 4 inches of stubble for ryegrass and 6 inches for small grains, so plants can recover. That residual leaf after grazing is essential for a fast regrowth period.

Regarding harvesting, the main challenge is the very low dry matter content of those forages, commonly under 20%, at least until heading. If harvesting for silage or hay, most producers will choose to wait for the first seedheads to appear, indicating the maximum yield potential without much loss in forage quality. Later harvesting can reduce forage quality and increase incidence of disease, lodging and related issues.

For ensiling, dry matter content should be above 35% to avoid clostridial (butyric) fermentation but no drier than 60% dry matter (40% moisture). Inoculant is recommended to help promote lactic acid-producing bacteria which, along with the high water-soluble sugar content, proliferate fast and decrease pH quickly. When baling hay, it will require a longer drying period, so aim for dry matter content greater than 85% (less than 15% moisture). In both cases, a mower conditioner is highly recommended to reduce drying time.

Ann Blount is a forage breeder with the University of Florida.

More resources

For more information on recommended varieties, please check our “Cool-Season Forage Variety Recommendations for Florida” and join us on a virtual tour of last year’s trial (2019-2020 UF/IFAS Cool-season forages variety updates). More information on regional variety trials can be found at Species & varieties-Forage variety trial information.