For many dairy producers, it will soon be time to feed the newly ensiled corn silage. Working in conjunction with their nutritional consultants, producers should have already sent corn silage samples to a laboratory for detailed analysis. Even with accurate analysis, there may be surprises in store that could mean some herds may not transition as expected to the new crop.

This will especially be the case in regions that experienced weather challenges, such as hail damage or extreme levels of moisture, that can often lead to plant disease, weed infestation, uneven growth rates and lower yields.

The fungal content of corn

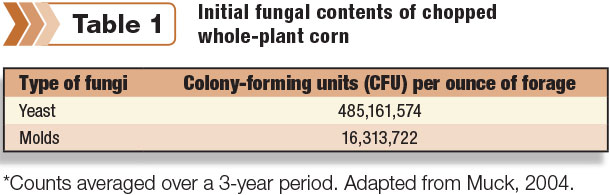

Naturally occurring fungi (yeasts and molds) are of interest in corn silage crops for various reasons. The whole corn plant in the field is not a sterile environment and is host to many different micro-organisms, even at the point of harvest (Table 1).

In the field pre-harvest, there are typically hundreds of millions of fungal colonies per ounce of corn silage. Assuming a cow eating 66 pounds per day of silage (fresh weight) containing 283.5 million colony-forming units (CFU) of fungi per ounce, she would have a concentration of approximately 2.5 million CFU of fungi per ml of rumen fluid.

These wild fungi could not only have an adverse effect on silage fermentation but also overall health and performance. This is another reason why good silage-making techniques, including the use of effective research-proven silage inoculants, is paramount to getting the most from your ensiled whole-plant corn silage.

The spoilage yeast challenge

Spoilage yeasts can multiply quickly, particularly when the silage is made or fed at warmer temperatures and especially without efficient silage-packing procedures, good face and feedout management and without using a silage inoculant proven to minimize the risks of yeast and mold.

High concentrations of spoilage yeasts in corn silage lead to an aerobically unstable crop, which is prone to heating in the initial stages of fermentation, during feedout and incorporation into a TMR.

The growth of spoilage yeasts also “steals” the most valuable and digestible energy and nutrients in the crop from the cow. Their presence in the silage fed can also have major negative effects in the rumen. Researchers have shown spoilage yeasts from feeding even relatively small amounts of challenged high-moisture shell corn mixed into a TMR significantly depressed milk yield.

Spoilage yeasts have also been linked to disruptions in ruminal volatile fatty acid production patterns and led to milkfat depression by interfering with the normal fatty acid bio-hydrogenation pathways. Recent in vitro studies showed the presence of spoilage yeasts from corn silage led to depressed neutral detergent fiber digestibility, which can negatively impact both dry matter intake and milk yield.

Therefore, there are potentially significant negative consequences on performance when a cow is fed corn silage compromised with high spoilage yeast concentrations.

The mold challenge

This past season, many growing areas experienced excessive moisture levels, which led to an increased presence of non-pathogenic rust and blight, particularly northern corn leaf blight. As the season continued, the newly formed corn ears on some stressed plants also showed signs of ear mold.

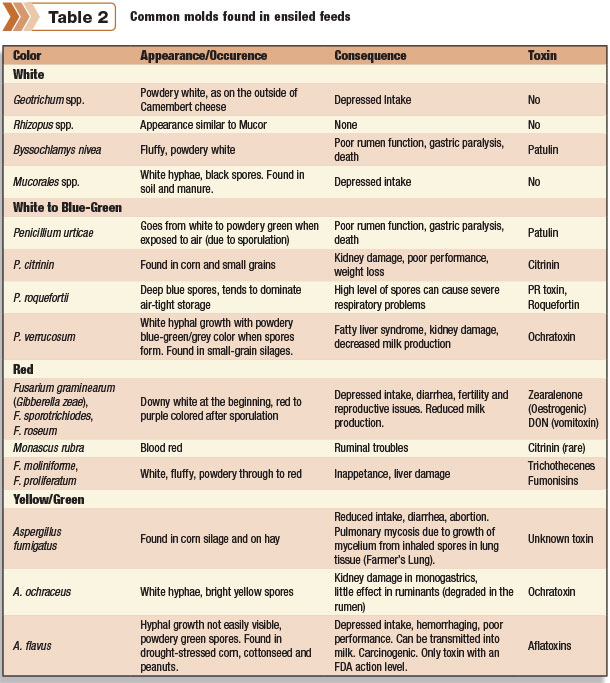

Table 2 shows some of the many types of molds that can potentially infest the ear of a corn plant, which may help identify the problem in the field. The significance of the presence of a particular mold in materials fed to dairy cows depends on the type of mold, the level of infestation and whether that particular mold is a known toxin-producer.

Even freshly chopped corn can contain high levels of mold, as shown in Table 1. Mold toxins are often referred to as mycotoxins and have many deleterious effects on animal health, fertility and productivity.

When taking representative corn silage samples for mold count, it is a good idea to ship the sample on ice. A mold count that comes back at less than 1 million CFU per gram (28.35 million CFU per ounce) should be safe to feed to dairy cows, assuming there is no mycotoxin challenge.

Between 1 million and 5 million CFU per gram of corn silage may require this particular silage to be diluted out with other forages with higher levels of hygiene in the ration to avoid the negative effects of depressed intake and fiber digestibility. The best defense is to apply good silage-making techniques and apply an effective inoculant with proven anti-fungal capabilities.

The recommendations above assume there are no issues due to mycotoxins. Whenever corn silage crops are known to have mold challenges, it is beneficial to analyze for mycotoxins. The absence of visible mold growth does not mean that mycotoxins cannot be present.

These potent, heat- and acid-stable toxins are likely to come in with the crop from the field and will not necessarily reduce in concentration during silage storage. In certain years, mold and mycotoxins can be regional (Aspergillus based in the south and Fusarium in the north).

Changing and unpredictable weather patterns across the U.S. have seen the widespread infestation of Fusarium and Gibberella spp. molds in 2015 corn silages, along with subsequent mycotoxins such as DON (vomitoxin), zearalenone and fumonisins.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

As with all forage crops, chopped corn will carry a load of naturally occurring fungi (wild yeast varieties, spoilage yeast varieties and mold varieties), typically in the millions of CFU per ounce.

Indeed, corn is harvested at a more mature stage than alfalfa or grasses for haylage – and so will carry a higher yeast and mold load than a typical haylage crop. This year’s corn silage crop was no exception, with many states experiencing early signs of non-pathogenic rust and blight followed by a significant infestation by ear corn molds during the growing season.

Steps taken to control and reduce the risk of the growth of these culprits at the time of ensiling include using a silage inoculant with proven anti-fungal properties, like the high-dose rate Lactobacillus buchneri 40788, and proper management of the silage during harvest and once in the storage structure.

Without these measures, 2015 silages may be prone to high fungal counts or mycotoxin content that can challenge cow health and performance.

If your herd performance is off-target this winter, consult with your nutritionist on whether spoilage yeasts, molds or mycotoxins are likely culprits and what potential mitigating steps are available. Plan now for the next season and use a research-proven silage inoculant to help minimize the risk of spoilage yeasts and molds for your next crop. PD

Tony Hall and Renato Schmidt are in technical services with Lallemand Animal Nutrition.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.