In the past year, two areas nutritionist investigations (and in some cases veterinary diagnoses) should better consider are starch digestion and feed hygiene.

In the feed hygiene area, one particular case with a dairy I have advised for several years comes to mind. The ramifications and outcomes in this case can provide valuable lessons for us. In the minds of many, the next several months to years in animal nutrition will play out with an increased emphasis on “clean feed” in order to improve dairy farm feed efficiency and profitability.

Unfortunately, because there may not be visual signs relating to feed hygiene issues, the impact and economic opportunities often go unrecognized if clinical symptoms (i.e., digestive upset) aren’t recognized on-farm. However, the following case study is an example of what could potentially be at play for your herd.

The dairy in this case study annually harvested corn for silage mid- to late August, then packed the fresh forage into a bunker and also bagged some forage for carryover feed the following harvest season. The bagged corn silage from the year prior was fed out during the following harvest season when the bunker was being refilled. This plan of attack is sound and valuable: to continually feed fermented corn silage for optimal starch digestibility and performance year-round.

However, the dairy habitually experienced rodent and bird damage with stored bags. The dairy management team recognized holes in the bags and aggressively disposed of visually spoiled feed, sorting through and feeding only “normal-looking” feed. This practice seemed to be adequate, as the herd did not experience dramatic changes in intake or with clinical digestive upset signs feeding out the bagged silage. Yet when reflecting on the bulk tank and, more importantly feed conversion, the situation looked decidedly different and costly.

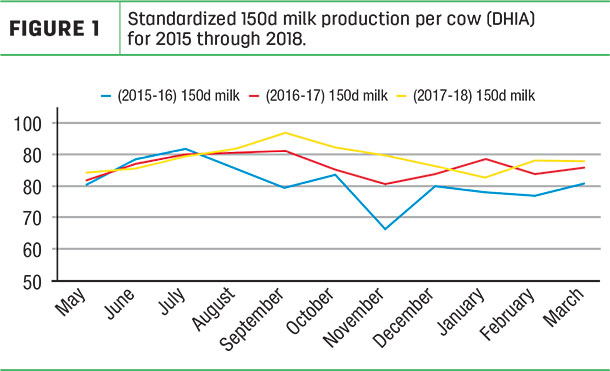

In Figures 1 and 2, three herd production years are shown graphically. In Figure 1, it’s clear herd performance (150-day standardized milk; DHIA calculation) trended down starting around August for 2015-16 and 2016-17, most notably in 2015-16.

This period corresponded to when the dairy began feeding bagged forage that had been damaged by vermin. Think of this like the gopher wreaking havoc in your favorite golf movie, as the drop-off in performance ranged from 5 to 20 pounds of 150-day standardized milk per cow.

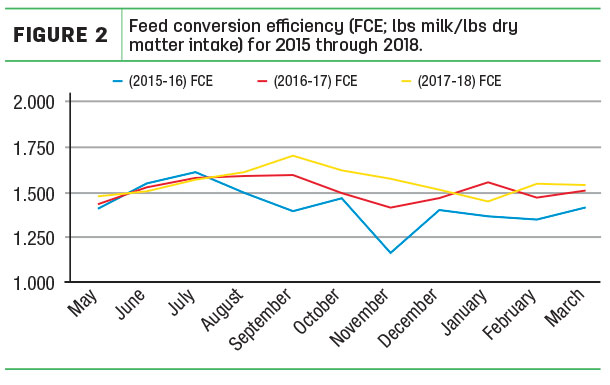

Beyond milk per cow, dairy management and advisory teams should also be tracking production efficiency metrics with today’s economic climate. Reason being, more milk per cow does not guarantee profitability if feed intake and costs associated are not accounted for. For example, there are dairies out there producing greater than 100 pounds per cow, yet they are under extreme financial stress. Feed conversion metrics, such as feed conversion efficiency (FCE; pounds of milk per pounds of dry matter intake) or feed costs per hundredweight (cwt) energy-corrected milk, better relate to dairy business profitability.

On this note, Figure 2 showcases feed conversion efficiency impact while feeding the compromised bag forage.

What does this mean economically? It’s clear FCE was hampered after July in two consecutive years. To translate this into economic impact, a 0.25-unit change in FCE corresponds to $1 in feed costs to produce the same cwt energy-corrected milk (at roughly 10 cents per pound of TMR).

No veterinary diagnosis was clear as to what caused the drop in feed conversion to milk. However, one could speculate that the dairy cattle’s rumens were dysfunctional and digestion hampered, there was a subclinical immune response diverting energy from production – or both.

Eventually, we recognized the opportunity, and the dairy management team purchased protective netting to provide a physical barrier between rodents and the forage. The bag damage and holes were eliminated, and more consistent performance and feed conversion followed. Note in both Figure 1 and 2 that, in 2017-18, performance and feed conversion did not drop around September.

Recapping the case now several years after the fact, the details of the story are vivid. The images of the rodent damage are clear in my mind like that of a gopher popping up through a fairway. Learn from our experience. Ensure your feeder and management team scout for plastic damage on bags, bunkers and piles.

Seal holes immediately if evident. To quantify potential opportunities, now we have better feed hygiene measures, such as fungal (mold and yeast) and enterobacteria counts that can help us benchmark feed deterioration. Review this case with your nutritionist and veterinarian, and benchmark your forages. Look for synergies between this case and your farm, then consider the unseen feed conversion and profitable opportunities that might be possible. ![]()

John Goeser earned a Ph.D. in animal nutrition from the University of Wisconsin – Madison where he currently serves as an adjunct professor in the dairy science department. He also directs animal nutrition, research and innovation efforts at Rock River Lab Inc. based in Watertown, Wisconsin.

-

John Goeser

- Director of Nutrition, Research and Innovation

- Rock River Laboratory Inc.

- Email John Goeser