The best investments you can make on your dairy often pay dividends in higher yields and intakes, less waste, healthier animals, and, ultimately, greater convenience, efficiency, and profits. That’s why it’s critical to invest in the right inoculant from the start. This article will explain the basic types of inoculants, which crops to use them on, and, finally, how to make specific choices based on the dozens of products competing for your inoculant investment dollars.

Skipping inoculation

Silage can be made without adding bacterial inoculant, but fermentation needs bacteria. If you don’t inoculate with the specific bacteria found in a quality product, you’re at the mercy of what’s naturally found on the crop in the field, and that’s not always a pretty sight.

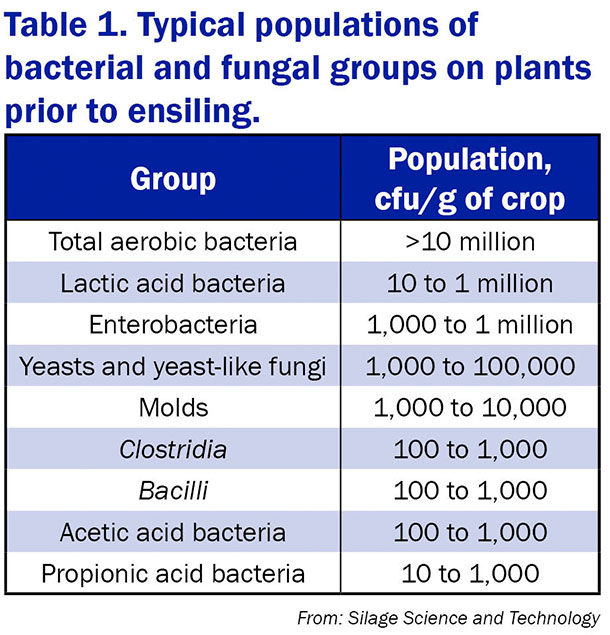

Millions of bacterial colonies are on every gram of feed in the field. One study from Silage Science and Technology (2003) showed more than 10 million colony forming units (cfu) of bacteria and fungi are found on each gram of forage. The alarming part is less than 10 percent of those organisms are the type that enhance an efficient, lactic acid-based fermentation. The “bad guys” typically outnumbered the “good guys.” In fact, the most prevalent bacteria in this sampling were enterobacteria, which can be pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli and other disease-causing bacteria.

Dr. Andy Beardsmore, one of the early leading proponents of bacterial inoculation, expressed this concept clearly.

He said, “There is a huge variation in the numbers of epiphytic (naturally occurring) lactic acid bacteria from crop to crop. Quite often, the naturally occurring bacteria are not high enough in numbers or are of the wrong species to achieve a lactic acid fermentation. Inoculation with a live culture should help direct the fermentation toward lactic acid production.”

Two basic inoculant types: Upfront fermenters and aerobic stability enhancers

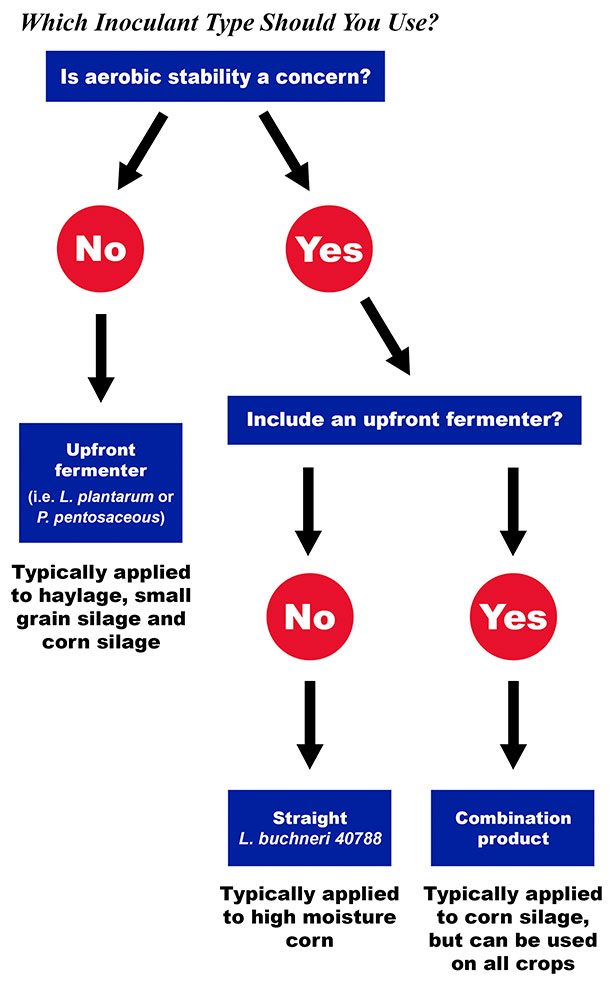

Which should you use? To answer this question, you need to determine if you encounter problems with spoilage or if a simple upfront fermenter will do the job.

For many years, inoculants were only used to drop pH quickly for a fast fermentation via lactic acid production. A rapid production of lactic acid minimizes dry matter losses and maximizes silage quality. Once the pH drops and the silage is not exposed to oxygen, feed quality can be maintained in storage for a long period of time.

If your feed is consistently put up at the ideal maturity, particle size, moisture and storage density, covered well, and feedout occurs without spoilage or heating, a simple upfront fermenter will suffice. This may seem like a tall order, but a fairly high percentage of feeds, including haylages, corn silage, grass silage and high moisture grains, are treated with a simple upfront fermenter very successfully.

Lactobacillus plantarum and Pediococcus pentosaceous are examples of bacteria you’ll find on an upfront fermenter label. Research has definitively shown that not all specific strains of bacteria are equally as effective. For example, L. plantarum MTD/1 is the specific species and strain Vita Plus uses in its Crop-N-Rich® inoculant. Trial data pertaining to this specific species/strain is not applicable to bacteria with similar names in other inoculants.

In summary, you might want to use a simple upfront fermenter if you have not typically seen signs of spoilage at feedout, which include heating, visible mold, high yeast or mold counts, or a “funky” smell at feedout.

Need some help with aerobic stability?

Lactobacillus buchneri-based bacterial inoculants extend aerobic stability by producing acetic acid, an antifungal compound. Although this class of inoculants has been around for a couple of decades already, their uses and advantages have only been studied more recently, especially in high-value feeds that may be fed off slowly, like high moisture corn.

Corn silage and high moisture corn (HMC) are high in starch and carbohydrates, which act as food for spoilage microorganisms (yeast and mold). Therefore, it makes sense that these crops seem to benefit significantly from the slightly higher acetic acid production and the resulting aerobic stability. By slightly elevating acetic acid in fermented feeds, spoilage organisms, such as yeasts and molds, can be prevented and aerobic stability enhanced.

L. buchneri thrives on previously produced lactic acid to create acetic acid. Thus, L. buchneri is often coupled with a lactic acid-producing upfront fermenter in a combination product, like Crop-N-Rich Stage 2 inoculant offered by Vita Plus, which uses a combination of the lactic acid-producing P. pentosaceous and the specific acetic acid-producing strain L. buchneri 40788.

L. buchneri can also stand alone, especially when applied to HMC, since the primary goal of treating HMC with L. buchneri is to limit spoilage. In addition, because HMC is drier than forage silage, the crop is more prone to spoilage and more inoculant bacteria are required, often one and a half times greater than the normal forage rate.

The flow chart below can help you decide which inoculant strategy is right for you.

This article has covered the two basic inoculation strategies: upfront fermentation and limiting spoilage. However, no additive will substitute good management. Do your best to harvest at the correct maturity, moisture and particle size, treat with a well-proven and well-researched inoculant, aggressively pack the feed into a sound storage structure, cover it with high-quality oxygen barrier plastic, maintain the storage structure integrity through the season, and manage the feedout face to minimize oxygen exposure. This investment greatly increases your chances of feeding high-quality forages and protecting your bottom line. ![]()

For more tips, visit the Vita Plus website.