According to recent national surveys, it is one of the most common causes of morbidity in adult dairy cows, affecting 99% of U.S. herds. With yearly prevention costs ranging between $70 to $100 per cow, and a variable estimated cost to an American farmer of up to $420 to $450 per case, the economic impact of this disease is evident.

Good indicators of udder health are bulk tank somatic cell count (SCC) and the rate of mastitis incidence. Somatic cells are natural immune cells that are always present in milk. They are mostly made of white blood cells, which concentration increases in response to infections by mastitis-causing bacteria. Through consistent efforts, farmers have improved udder health of their herds, reaching an average milk-weighted bulk tank SCC of 194,000 cells per milliliter in 2015, 25% lower than 10 years prior. However, despite advances in treatment and prevention, mastitis incidence increased from 13% to 25% in the same time frame (mostly due to better detection). This means that, on average, 25 out of 100 cows have a case of clinical mastitis in the current lactation.

Cows with stronger immune systems do better job of fighting off mastitis-causing pathogens

Multiple factors contribute to mastitis rates, such as environment and facilities management, milking parlor equipment and maintenance, milking procedures and herd genetics. Diet is often overlooked as a contributing factor, but many nutrients play a role in maintaining and boosting dairy cows’ immune systems. Although poor nutrition alone doesn’t necessarily cause mastitis, it can make it easier for bacteria to break through cows’ immune defenses and establish themselves in the udder, resulting in more cases.

The immune system has numerous different components, both pathogen-specific and nonspecific, which can reduce or eliminate bacterial invasion of the mammary gland. Nutrition can impact these components in a variety of ways, resulting in either suboptimal or boosted immune function. First, immune cells require specific nutrients, and when cows are fed a diet lacking them this can impair their defenses, all the while still providing proper nourishment for other important functions, such as milk and components production. So while a diet might support substantial milk production, at the same time, the risk of mastitis can increase due to deficient immune function. Second, proper nutrition can reduce the occurrence of metabolic conditions (e.g., fat cow syndrome, ketosis, hypocalcemia) that suppress immunity, helping reduce the risk of mastitis. Finally, nutrition can go beyond meeting requirements and boost immune function beyond average.

Nutrition can play significant role in bolstering the cow’s immune system

Up to three-quarters of all clinical mastitis cases occur in early lactation, with the majority of these being diagnosed in the first few weeks postpartum. This is in part due to the high incidence of metabolic disorders, which not only negatively impact production performances but also negatively affect cows’ immune functions. Late-lactation and dry cow diets should be formulated with the right levels of energy to avoid under- (body condition score less than 2.75) or overconditioning (body condition score greater than 3.5) animals approaching parturition. Both these scenarios have been linked to a failed transition into lactation and an increased risk for immune-suppressing conditions. Non-optimally conditioned cows will then face transition with a higher risk of contracting mastitis.

Calcium balance should also be a focus of transition diets, as cows that develop milk fever have a much higher risk of developing mastitis. Lack of calcium affects the udder both directly and indirectly. Immune cells need calcium to properly functionl; so do the muscles of the teat-end sphincter, the physical barrier that prevents bacteria from entering the udder. Affected cows tend to also spend more time lying down, increasing udder exposure to pathogens, and have greater plasma levels of cortisol, a stress hormone capable of suppressing immune functions. Formulating dry cow diets to provide proper amounts of calcium, phosphorus and magnesium, and to contain the correct cation-anion balance, can reduce the incidence of mastitis via improved calcium status.

Out of all the nutrients that affect immunity and prevent mastitis from occurring, trace minerals like selenium, copper, zinc and vitamins like vitamin A/beta-carotene, vitamin D and vitamin E are among the most researched and those with the greatest effects on udder health. As building blocks in the cow’s antioxidant system, they help prevent damage to cells throughout the animal body, including the mammary gland tissue and the immune cells. Most of the time, formulating diets to include an adequate amount of these micronutrients and meet their recommended requirements will allow you to maintain proper immune function. Increased doses of vitamin E and selenium beyond NRC requirements have been proven effective in lowering SCC and mastitis incidence, while all other mentioned vitamins and minerals have shown inconsistent results when fed beyond the requirement.

Although vitamins and minerals play an important role in the functionality of the immune system, be careful and well aware about feeding too much of the latter, as this can be harmful. It’s all a balancing act. As updated requirements have been published in late 2021, it’s now a good time to work with your nutritionist to ensure your diets meet the new guidelines.

Research shows that postbiotics can have a positive impact on reducing mastitis

At the end of the day, the goal is to feed the immune system in a way that helps maintain udder health. Incorporating these key micronutrients is crucial and impactful. However, we can go a step beyond and incorporate feed additives as supplements to get additional beneficial effects. Nutritional interventions that emphasize the immune system and prevention, rather than curing mastitis, have been of great interest to researchers, feed companies and producers, especially with the objective of reducing antibiotic use in dairy operations. This is where a natural postbiotic feed additive comes in. Research has shown the direct benefits of feeding a postbiotic feed additive to dairy cows on their udder health.

2021 University of Illinois trial

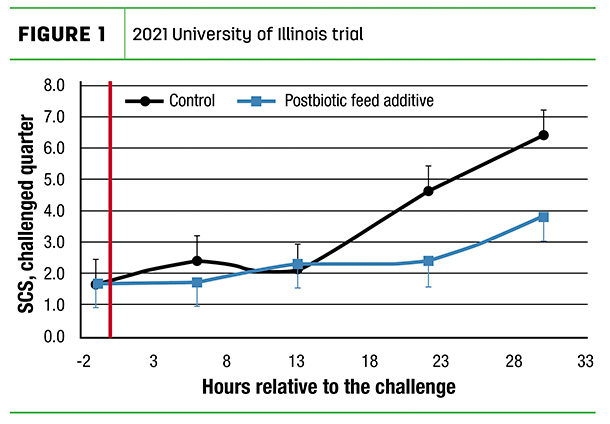

Promising results concerning the positive effects on udder health (e.g., reduced mastitis incidence and somatic cell scores) of postbiotic feed additives, specifically a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product (SCFP), were first reported by Dr. Jim Ferguson (U Penn Vet School) in 2018. To better understand their mechanism of action, Dr. Juan Loor (University of Illinois) conducted a study to evaluate the impact of SCFP postbiotic, during a case of clinical mastitis. Cows were either fed a control diet or a diet supplemented with a SCFP postbiotic additive. They were then infected in the right rear quarter with 2,500 cells of Streptococcus uberis, a common environmental mastitis pathogen. After 36 hours, udder tissue samples were collected and antibiotic treatment started. At the end of the challenge (36 hours post-infection), the SCC of the infected quarter was fourfold greater in control cows compared to those that consumed the postbiotic feed additive (Figure 1).

This was due to greater pathogen-killing capacities of their immune cells and an increased resistance to damage of their udder tissue compared to control cows. These boosted defenses allowed postbiotic-fed cows to maintain higher feed intake and milk yield both during the challenge and in the month following it.

2020 Iowa State University trial

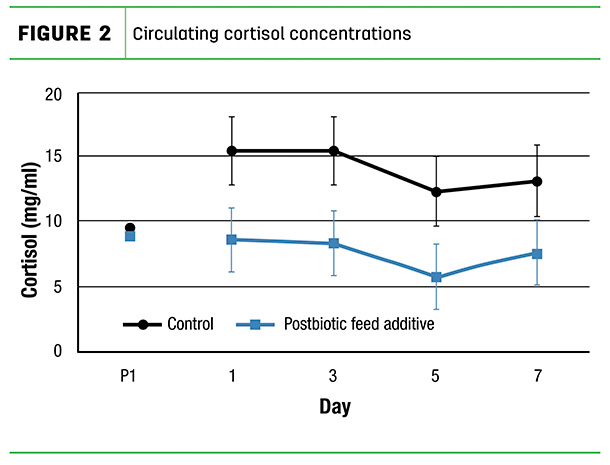

Heat stress can also compromise the reproduction, productivity and health of a dairy cow. Among these negative effects, the decreased milk production and increased bulk milk SCC during summer are the most recognized and directly related to udder health. For example, Dr. Lance Baumgard’s lab (Iowa State University) included an SCFP postbiotic feed additive in dairy cows’ diet and then subjected them to a weeklong heat stress challenge via electric heat blankets. Compared to control cows not fed the postbiotic additive and also subjected to heat stress, SCFP-fed cows had almost 50% lower plasma cortisol, the stress-related and immune-suppressant hormone, and higher amounts of immune cells (9% to 26% more) in their blood (Figure 2).

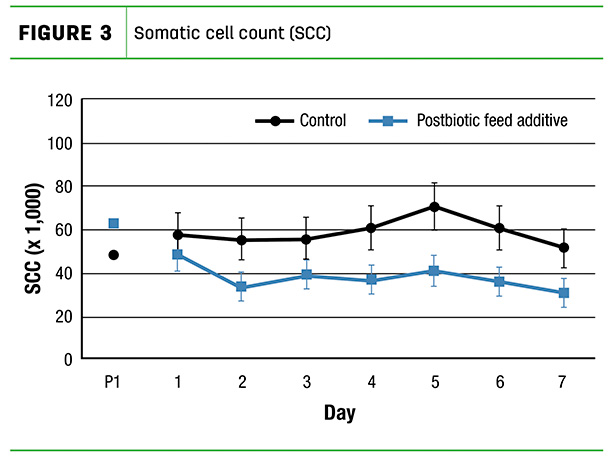

So it is no surprise that postbiotic-fed cows had a 36% lower SCC during the intense heat stress challenge (Figure 3).

Nutritional prevention is a key element to udder health

Nutrition plays a vital role in the functionality of a cow’s immune system. It works synergically with the cow’s physiology to maintain its overall health and optimal immune strength. Deficiencies in key nutrients will greatly reduce dairy cows’ immune defenses. So feeding to requirements without cutting corners must be the basis of every dairy operation. However, new research shows that targeted supplementation can boost immune function beyond what is considered normal or average. This allows herds to better tolerate common production stresses and udder challenges for overall health and performance.

As the immune system does not solely focus on defending the mammary gland, nutritional strategies to boost udder health, such as incorporating a postbiotic feed additive, will have great effects on all other systems. And generate returning benefits in reproduction, gut, feet and respiratory health. ![]()

Staff photo.

-

Mario P.E. Vailati Riboni

- Technical Service Specialist

- Diamond V

- Email Mario P.E. Vailati Riboni