Success begins with an end in mind. Think trajectory. Think reverse engineering. If you want age at first calving (AFC) to be 21 or 22 months old, you better have an “end” weight and frame modeled into your growth system.

I’m talking the proper nutrition, facilities and management to achieve the desired weight and height before calving: 95 percent of mature bodyweight and 96 percent of mature hip height. Many believe the ideal AFC goal is 22 months – and for some dairies, it is. However, for many dairies, it is not.

When I ask dairy farmers why their AFC goal is 22 months, many of them reference industry data instead of their own data.

Most dairies already have the data they need to discover their farm’s “sweet spot” for AFC. By sweet spot, I mean the most profitable age animals should enter their milking herd. You can define profitability a few ways: energy-corrected milk, component yield, component efficiency, etc. For sure, we want replacement animals to be higher profit centers than the animals they are replacing.

Calving animals at an earlier age is no guarantee they’ll make you more money. Yes, you can save feed input cost because you get them into the milking string sooner. You just better make sure the milk output more than pays for the feed savings. Don’t get me wrong – AFC can be 21 or 22 months; for some dairies, though, they are better off at 23 or 24.

Lactation curves or summit milk might be a good place to begin the investigation. For example, do heifers with an AFC of 21 to 22 months achieve equal or greater summit milk than older heifers? Or pick a test day and compare lactation curves across AFC.

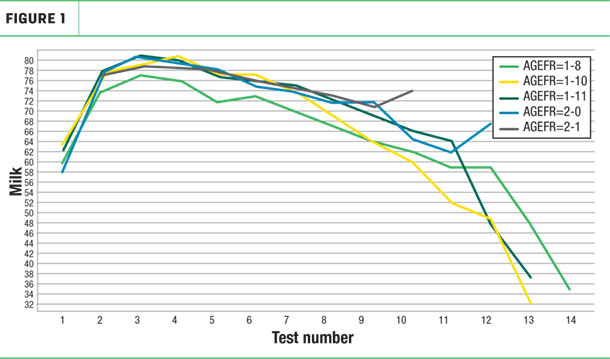

In Figure 1, animals that calved at 21 months (green line) and 22 months (yellow line) did not achieve or sustain the same levels of milk production as the animals that calved at 23 and 24 months old (dark and light blue lines).

The animals that calved at 22 months old had high milk on test number 4, but persistency was poor, as these animals ended their lactation significantly lower than heifers with an AFC of 23 and 24 months. Visual appraisal of these animals would confirm poor body condition and an inability to meet lactation demands through nutrient intake.

A thorough review of your growth system will help determine the AFC sweet spot. Because so many factors – nutrition, facilities, labor, management, forages – factor into the profitability equation, aligning these variables with the breeding program becomes crucial. Any bottleneck, in any of these areas, could preclude an early AFC.

Meaning, if 95 percent of mature bodyweight before calving cannot be achieved by 22 months, the system will not deliver, and you’ll end up with 22-month-old heifers without proper body size. Matching the growth system to the AFC sweet spot can often reap rewards of 10 pounds of milk or more in first-lactation performance.

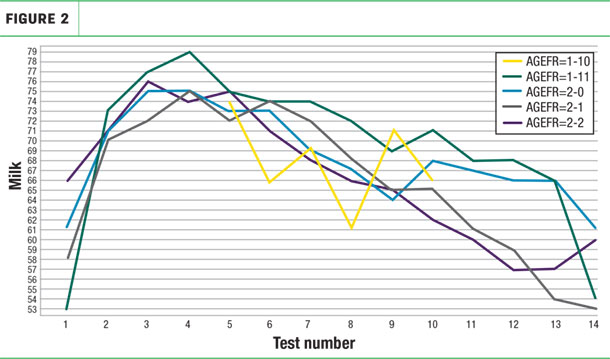

Let’s look at another herd (Figure 2) and see a huge disparity in milk production for the varying AFC. In this chart, the sweet spot for AFC would be 23 months (AGEFR 1-11) for this herd.

These animals were likely more physically mature, meeting the required 95 percent mature bodyweight before calving.

Of the utmost importance is: Each dairy, being unique in their facilities, forages, managements, etc., reviews their entire growth system to identify the AFC goal that is most profitable. Analyzing the data from a range of AFCs is a great place to begin the discussion.

Do desired AFC goals match up with current nutrition or facilities? Is the management team willing to make changes and monitor animals to achieve the desired AFC goal? I’m not convinced one AFC goal is best for all dairies; too many variables exist across dairy farms.

One could divide the growth system into five bodyweight (pounds) segments: 300 to 500, 500 to 700, 800 to 900 (breeding), 900 to 1,100 and 1,100 to 1,300.

Consider these calculations:

- Mature bodyweight: 1,450 pounds (This is determined in fourth-lactation cows at 140 days in milk.)

- 95 percent mature bodyweight (before calving) = 1,377 pounds

- Breeding weight (55 percent mature bodyweight) = 798 pounds

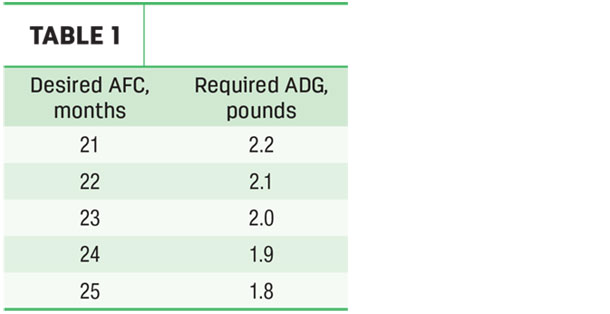

A dairy with an AFC goal of 21 or 22 months will need 2.2 pounds or 2.1 pounds of average daily gain, respectively (Table 1).

These gains require a higher plane of nutrition and associated management from start to finish. Are you weighing and measuring height of heifers throughout the growth system? If not, you are not fully informed as to what your AFC should be.

And you don’t have enough information to change your system to meet a new, more aggressive AFC goal. I love seeing intake data because it makes it easier to formulate metabolizable energy and protein (amino acid) levels for the diet.

One of the common mistakes I see is a lack of weight and height measurements during the final two growth phases. On many dairies, once heifers are bred, we get complacent and assume growth will continue and stay on track.

But unless these animals are carefully managed and fed the nutrients they need, it can be easy for them to regress and fall short of the required mature bodyweight after calving. This will ultimately limit their lifetime performance and profitability.

Today, we have access to advanced ration models and management software to better model the growth system for heifers. Honestly, there really is no reason to not have weight and height data; advisers are guessing to some degree trying to match AFC with average daily gain without this data.

Whether we modify nutrient intake, labor, facilities or management, we must keep the end in mind. I know, it’s a lot to consider. Then again, there’s nothing more important to your profitability than the productivity of your heifers.

We make the most profitable decisions around AFC when we analyze the entire growth system and identify the sweet spot for each farm. Don’t like your current sweet spot? Change it – but do it with a plan and lots of data. ![]()

-

Christopher J. Canale

- Technology Manager

- Cargill Animal Nutrition

- Email Christopher J. Canale