Grain corn, silage corn – you name it, there were problems. This wasn’t the only foliar disease of corn though; we also had to deal with northern corn leaf blight (NCLB), gray leaf spot (GLS) and various ear and stalk rots. It was a generally challenging season all around.

While I’ll spend most of my time here talking about tar spot, don’t forget about foliar diseases like NCLB and GLS. In the north-central U.S., NCLB and GLS have been more widespread and consistent pathogens over recent years compared to tar spot. Tar spot has a lot of people’s attention, but we can’t forget to consider and manage NCLB and GLS. These diseases can impact yield and silage quality significantly, and much is known about how to manage them.

Be sure to choose hybrids with resistance to the primary foliar disease you have on your farm, and plan your primary disease management plan around that disease of most importance. Don’t change everything for tar spot management. We know little about this disease, and it might not even be a significant player in 2019 – only time and weather will tell.

What causes tar spot?

Tar spot is caused by the fungal pathogen Phyllachora maydis. This pathogen was first confirmed in the U.S. in 2015 in Illinois and Indiana. In 2016 and 2017, it spread to other states including Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa, to name a few. Phyllachora maydis is well-known as a pathogen of corn in Latin America. In that environment, there is actually a second pathogen, Monographella maydis, which works in complex with P. maydis to cause damage on corn. Work across the Midwest U.S. in 2018 focused on trying to find Monographella maydis. However, it has never been identified from corn in the U.S. Thus, we believe P. maydis is the pathogen causing the damage we observed from tar spot in the Midwest.

Why was tar spot so bad in 2018?

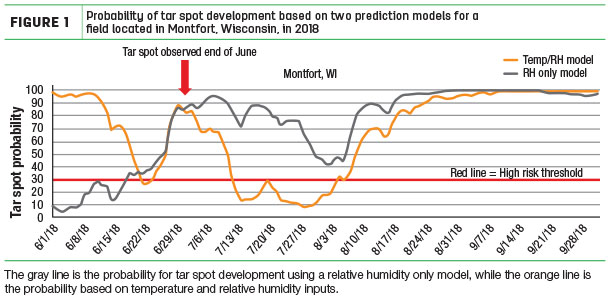

It was all about the weather. The 2018 field season was made up of long durations of optimal temperature and moisture, leading to the extensive epidemic we observed. Researchers in 1995 reported monthly average temperature between 63ºF and 72ºF, average monthly relative humidity of 75 percent, excessive leaf wetness at night, 10 to 20 foggy days per month and monthly rainfall totals of 6 inches or more were all contributors to increased risk of tar spot epidemics. In fact, based on this information, research in 2018 showed the Upper Midwest has a climate favorable for tar spot. We also performed our own modeling using relative humidity or temperature and relative humidity to describe the risk of tar spot development based on the epidemics of 2018.

In a field near the epicenter of the epidemic in Wisconsin (Montfort), our models demonstrated weather was favorable and risk elevated for a period of time in June and a second extended period in August (Figure 1).

These two “peaks” of extended risk show that the weather was very favorable for the pathogen for a large part of the field season. The early season risk coincided with the first observations of tar spot in the area, which is when the corn crop was generally very susceptible to yield loss and quality reductions from a foliar pathogen. In 2019, should periods of high humidity and rain coincide with cooler average temperatures, risk for tar spot development will be high.

What are the impacts of tar spot on silage corn?

Under severe epidemics of tar spot, it appears silage corn can be significantly affected. Anecdotal evidence from the 2018 epidemics showed substantial increases in nondigestible fiber components of silage corn could be the result of tar spot infection and early drydown. Even more significant was the issue of rapid drydown resulting in extremely poor moisture levels for making quality silage.

In many cases, silage hybrids hit hard by tar spot had suboptimum moisture. This issue, combined with delayed harvest due to rain, made this situation worse. Low moisture resulted in poor packing of bunkers, slow fermentation and slow drop in pH. Improper fermentation has subsequently led to increases in mold and other associated problems due to the lack of quality packing.

What should we do to manage tar spot in 2019?

Corn hybrids do vary in their resistance to tar spot. However, note that no hybrid seems immune. Take time to understand how susceptible the hybrid is that you planted in 2019. Should it be considered fairly susceptible, frequent scouting will be necessary to make a decision to potentially spray a fungicide. Paying attention to weather will also be critical in 2019. Should the weather become consistently wet with moderate temperatures, and you notice some tar spot showing up, a fungicide might be needed.

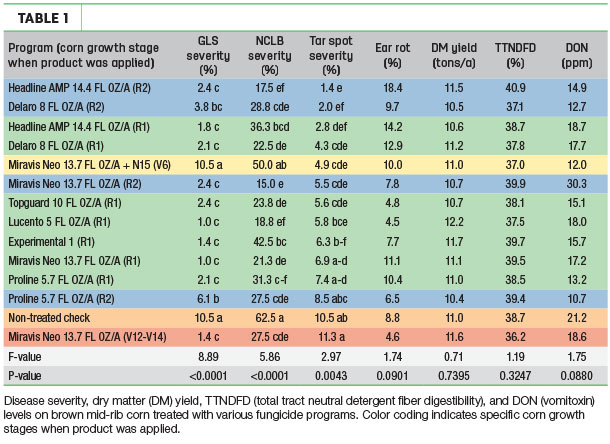

Spraying a fungicide early in an epidemic will be key to maximizing the benefits of spraying a fungicide. In 2018, we conducted a fungicide trial on BMR silage corn in Wisconsin. The results of the trial are in Table 1.

Most products resulted in some reduction in tar spot severity on ear leaves on the day the plots were chopped. However, maximal benefits were observed with application of fungicide with two or three modes of action combined with application timings around the silking (R1-R2) corn growth stage.

Summary

There will likely be tar spot in the Corn Belt of the U.S. Where and how much will depend on many factors. However, careful scouting and attention to weather can help you make in-season management decisions. Know your hybrids and their potential susceptibility to tar spot. Prioritize fields with susceptible hybrids for scouting and intervention. If you choose to use a fungicide, remember to use a mixed-mode-of-action product and apply early in the start of the epidemic. Once the epidemic is solidly underway, fungicides will have a very minimal effect. ![]()

PHOTO: Tar spot shows up as “fish-eye” spots on leaves of a corn plant. Photo provided by Damon Smith.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Damon Smith is an associate professor, in the department of plant pathology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Email Damon Smith.