To record the fastest sprint in history, Bolt relied on an adaption in his body’s metabolism that generated the short burst of energy his muscles required. Amazingly, changes in Bolt’s metabolism when racing are also used by the dairy cow to meet her energy demands in early lactation. To appreciate this metabolic adaption, let’s first consider the remarkable changes in energy metabolism that occur in the dairy cow as she transitions from pregnancy to lactation.

How does a cow produce 8 pounds of glucose?

A dairy cow producing 100 pounds of milk needs around 8 pounds of glucose. To get this amount of glucose, the cow needs to produce it all by herself. Where most of the dietary carbohydrate we eat is absorbed into the bloodstream as glucose, under typical conditions the dairy cow has minimal glucose pass into the bloodstream from intestinal absorption because most carbohydrate is fermented in the rumen. Therefore, to get the glucose she needs to support maintenance, growth, reproduction and lactation, the dairy cow relies almost entirely on the liver to produce glucose.

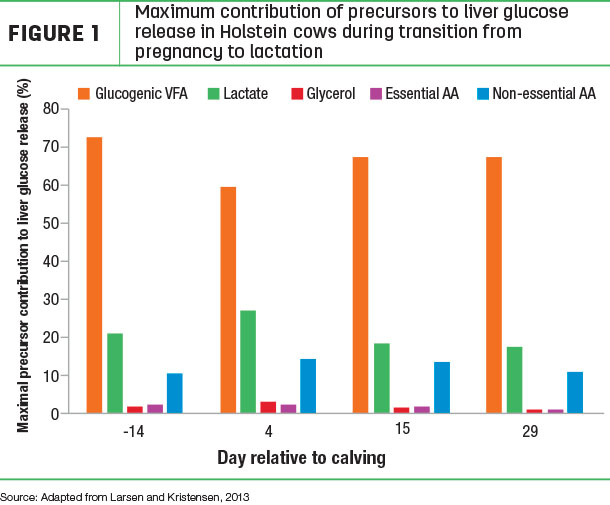

The liver builds glucose from volatile fatty acids (VFA) produced during the fermentation of feed ingredients in the rumen. Although propionate is the primary VFA that serves as a glucose precursor, contributing between 60% to 75% of glucose production, other VFA, namely isobutyrate and valerate, lactate, glycerol and amino acids are also glucose precursors (Figure 1).

As the second-most-important precursor, lactate can contribute to as much as a third of total glucose produced by the liver in an early lactation cow.

In early lactation, because of the high energy requirement to make milk, cows need to produce much more glucose. Unfortunately, the cow cannot increase fast enough the amount of glucose precursors coming from the rumen. When this occurs, glucose release from the liver becomes more dependent on lactate as its relative contribution increases, while for propionate it decreases (Figure 1). So if the cow is using so much lactate to make glucose, where is the lactate coming from, and what is the similarity in metabolism to Usain Bolt as he competes?

Like Usain Bolt, the cow generates its own lactate

Although lactate can be generated through rumen fermentation of feed ingredients, typically the amount of lactate produced is low. Therefore, to meet its need for lactate, the dairy cow generates its own lactate from glucose (stored as glycogen) in muscle and adipose tissue. This same process of breaking down glycogen to lactate is used by Usain Bolt’s muscles to generate the energy he needed to make him the fastest person alive.

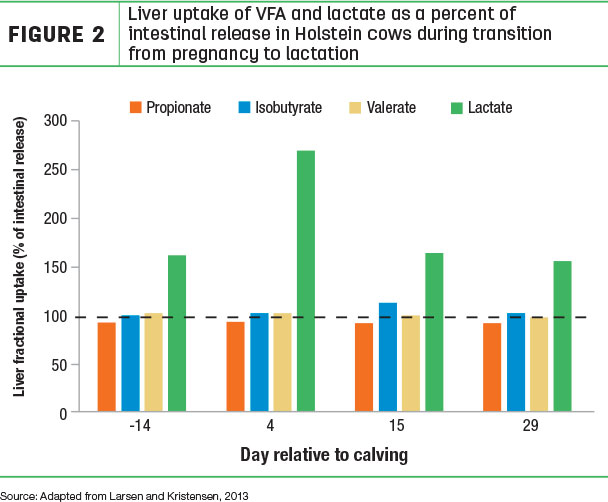

And like with Bolt, during the first 30 minutes after his race, the dairy cow takes up the lactate released into the blood and uses that as a precursor to make glucose. This is demonstrated in Figure 2, which shows that both before and after calving in the dairy cow, the liver takes up more lactate than is absorbed by the intestine.

This means at no point is lactate absorption enough to exceed the liver’s capacity to use lactate as a glucose precursor. In addition, immediately after calving, lactate uptake by the liver increases to nearly twofold above what is absorbed from the intestine, demonstrating the importance of lactate when cows are in negative energy balance. This raises the question: If dietary supply of lactate could be increased, would this improve glucose production and overall liver function in the early lactating dairy cow?

Finding a safe form of dietary lactate to meet the cow’s glucose needs

High levels of rumen lactate production can be generated in the dairy cow through a sharp increase in feeding highly fermentable carbohydrates. However, in this case, the fermentation-induced increase in rumen lactate can drive rumen pH down, and the resultant rumen acidosis can adversely impact the health status of the cow. Therefore, manipulating the feeding of traditional feed ingredients is not a viable option for increasing rumen lactate and its availability to the cow for glucose production at the liver. On the other hand, there is a feed ingredient that contains high levels of lactate as ammonium lactate, as well as bacterial and yeast culture, and can be fed without the risk of acidosis.

Ammonium lactate maintains rumen pH

Over 60 years ago, it was shown that the nitrogen in ammonium lactate influences rumen fermentation differently than other forms of non-protein nitrogen (NPN), with ammonium lactate bringing greater nitrogen utilization and carbohydrate digestion and lower ammonia in the rumen than a combination of urea and glucose. Recent data from Ohio State University also demonstrates how the ammonium lactate-based feed ingredient can bring beneficial changes in dual-flow continuous-culture rumen fermentation over a high-energy and -protein ingredient such as soybean meal (SBM).

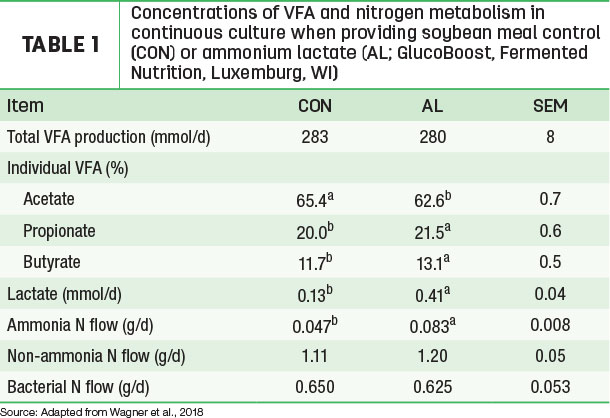

The experiment found that when the feed ingredient substituted some SBM to maintain the diet at the same level of nitrogen content, propionate production and concentration of lactate increased without adverse effects on rumen pH (Table 1).

This indicates that feeding ammonium lactate can increase the availability of the two key glucose precursors used by the cow. In addition, despite ammonium lactate substituting feed protein from SBM with NPN, non-ammonia nitrogen and bacterial nitrogen flow did not change (Table 1). This suggests the nitrogen in ammonium lactate can be efficiently incorporated into high-value microbial protein.

Improved feed efficiency and liver function with ammonium lactate

The importance of lactate for the early lactation cow and the improvements in rumen fermentation with an ammonium lactate-based feed ingredient that we have outlined provided a stimulus for a more detailed assessment of its effects on whole-animal metabolism. Recently, an early lactation dairy cow study was completed at the University of Wisconsin that evaluated the effect of the feed ingredient on rumen fermentation, liver energy metabolism and overall animal performance. In a follow-up article, we will describe the positive impact of ammonium lactate on feed efficiency in early lactation as well as improvements on liver glucose and fatty acid metabolism. ![]()

ILLUSTRATION: Illustration by Corey Lewis.

Heather White is an associate professor in the department of dairy science at the University of Wisconsin.

-

Michael de Veth

- Vice President of R&D

- Fermented Nutrition

- Email Michael de Veth