Most pastures in the Upper Midwest consist of perennial cool-season species. These grasses and legumes grow well in Midwestern soils and climate, and are considered high-quality forage options that provide adequate nutrition for grazing dairy cows. The decreased feed availability in pastures because of slower growth of these forages may lead to decreased milk production. In addition, farmers may have to feed stored forages, which can increase their feed costs. Incorporating warm-season annual grasses into pasture systems has been suggested as a solution, as these grasses will experience their fastest growth rates at the time cool-season perennials may have delayed growth. Some farmers may be hesitant to implement this solution, as it is generally believed warm-season annuals have lower forage quality than cool-season perennials.

An approach to increasing diversity in a farm’s forage base is to combine annual and perennial crops in separate pastures. An example for the northern U.S. would be to use cool-season grasses and legumes for forage in spring and early fall, and warm-season annuals like teff and sudangrass for forage in summer. Grazing systems using these different approaches to achieve diversity require biological, environmental and economic analysis.

Warm-season summer annual grasses

Researchers at the University of Minnesota West Central Research and Outreach Center have been studying BMR (brown mid-rib) sorghum-sudangrass and teff grass, as grazing dairy farmers in Minnesota are beginning to incorporate these grasses in their grazing programs and are interested in learning more about them. We wanted to determine how the forage quality of annual warm-season grasses compare to perennial cool-season pasture mixtures, as well as how they influence milk production and health parameters in grazing dairy cows.

For our study, 90 organic dairy cows were used to compare two different pasture systems at the West Central Research and Outreach Center in Morris, Minnesota. The first system (cool system, System 1) included a diverse mix of cool-season perennial grasses and legumes such as perennial ryegrass, white clover, red clover, chicory, meadow bromegrass, orchardgrass, meadow fescue and alfalfa. The second pasture system (warm system, System 2) was a combination of the cool-season perennial mixtures and warm-season annuals BMR sorghum-sudangrass and teff grass. Perennial pastures were established in 2012. Warm-season annuals BMR sorghum-sudangrass and teff grass were planted in individual paddocks during the third week of May of each year.

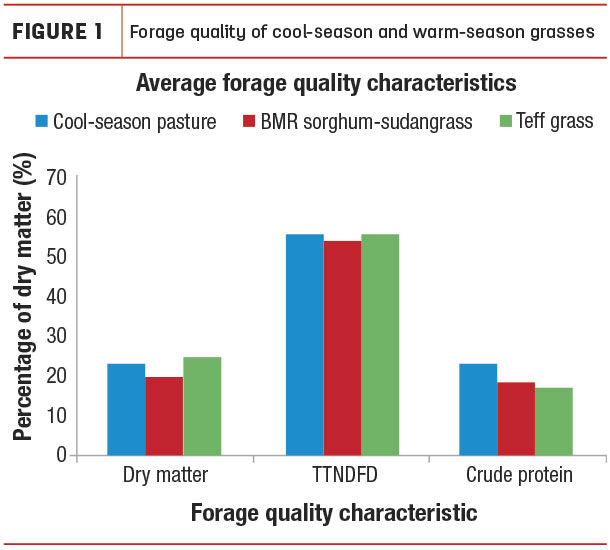

Forage samples were collected daily throughout the grazing seasons of 2013 through 2015. Dry matter was analyzed immediately after sample collection. Forage samples were tested at Rock River Labs in Watertown, Wisconsin, for the forage quality characteristics neutral detergent fiber (NDF), total tract NDF digestibility (TTNDFD), crude protein (CP) and mineral content.

Forage quality was similar between cool-season perennial pasture grasses and the warm-season species evaluated in this study (Figure 1). Cool-season pasture had higher average crude protein (23 percent) than the warm-season grasses, but BMR sorghum-sudangrass and teff grass still had adequate levels of protein for lactating cow diets (18.5 and 17.5 percent, respectively). Dry matter was higher in cool-season pasture (23 percent) and teff grass (24 percent) than BMR sorghum-sudangrass (20 percent). TTNDFD was similar between all types of forage. Mineral composition varied between the different grasses.

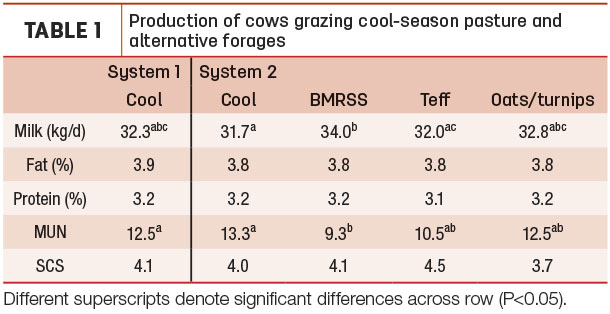

There were no differences in milk production, components or somatic cell score between cows grazing only cool-season pastures and cows in a system that incorporated warm-season annuals. Average milk production was 32.3 pounds for the cool system and 32.5 pounds for the warm system. When cows switched from grazing cool-season pasture to BMR sorghum-sudangrass, production significantly increased by 2 pounds per cow per day (Table 1). There was also no difference in body condition score, bodyweight or activity between systems. Cows in both systems followed similar trends in production, including decreased production during times of high temperature and humidity.

During the first year of the study, cows in the cool-season system needed to be supplemented with stored feed in a TMR due to a shortage of forage biomass in pasture, while cows in the system incorporating warm-season grasses were still able to graze. The following year, there were no differences between pasture systems. Therefore, warm-season annuals in grazing systems for dairy cattle may be beneficial in certain years to compensate for weather that affects pasture production. Warm-season grasses like BMR sorghum-sudangrass and teff grass may be incorporated into a pasture system for grazing organic dairy cattle without sacrificing forage quality. Milk quality and production can also be maintained when warm-season grasses are incorporated in a grazing system for organic dairy cattle.

Grazing systems using these different approaches to achieve diversity require biological, environmental and economic analysis. Pasture management and forage species selection within a farm can influence the forage quality of pasture forage for grazing dairy animals. ![]()

Kathryn Ritz is a research associate at the University of Minnesota.

-

Bradley J. Heins

- Associate Professor

- Organic Dairy Management

- West Central Research and Outreach Center

- University of Minnesota

- Email Bradley J. Heins