During the Spring quarter at UC – Davis, our dairy cattle production class of 40 students was on the road again doing weekly field trips to 10 dairy farms. We traveled all of California, as far north as Orland and as far south as Hilmar. The objectives were to meet with producers and talk about management practices and issues facing the industry, to meet with professionals in the field (nutritionists and veterinarians) and to look at facilities and animals.

The students heard a similar story at many field trip visits – there is too much milk in the industry and there are caps on milk production output at the farm level. Producers are limited on how much their creamery or co-op will accept above the dairy farmer’s established production base.

One common theme the class heard over and over again was that producers culled cows to lower milk production, but milk production actually increased.

One producer told the class that after culling between 70 and 80 cows in a week, milk production jumped to where the dairy was actually shipping more milk after cows were culled than prior to culling. Another producer told a similar story.

He culled cows and culled more cows to the point that he had no more cows on his list to cull, but he got a call from a representative at his co-op telling him that his milk production had been increasing steadily and that he had to reduce his milk shipped. The message was repeated many times: I culled cows but milk production increased with fewer cows.

Stocking density is often something not given much management consideration. Having a production string of lactating cows that is over 100 percent capacity was not uncommon on field trip visits over the past few years.

It was an excellent learning experience for the students because they often think that the number of cows in a pen equals the number of freestalls or lockups at the feed manger. That is often not the case. In fact, the effect of stocking density is rarely discussed with respect to either milk yield or cow health.

Because I do nutrition research on campus, stocking density is an important factor with respect to feeding. In our research studies, we feed each cow individually using electronic feed doors.

Our experimental treatment is usually given through the diet (TMR), so we cannot group feed because we are assigning the treatment to the cow.

Why feed each cow individually? Because cows will sort, particularly when in a group situation when stocking density (number of cows/number of lockups at the feed manger) is greater than 100 percent.

If we formulate a TMR to provide the proper nutrients and energy for milk production for a given feed intake to meet the genetic potential of the cows, then sorting defeats the purpose of feeding a TMR – it reduces the positive impact of a TMR. Last year, we published an article that discussed the impact of slug feeding on milk production and milk composition.

Stocking density with more cows than lockups at the feed manger does not allow all cows to eat at one time, and this scenario can create problems where cows will slug feed.

Feeding a TMR after milking with more cows than headlocks at the feed manger allows the first cows at the manger to sort the TMR. The next cows eating at the feed manger do not consume the same TMR with respect to energy and nutrients.

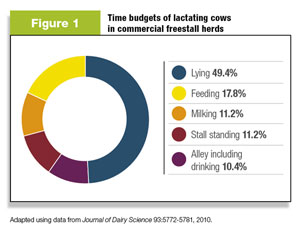

Time budgets of lactating cows in commercial freestall herds provides background information. ( See Figure 1 .)

Cows spent almost 50 percent of their time lying in freestalls and about 18 percent of the day feeding – 67 percent of the daily activity was resting and eating.

Stocking densities that have more cows than freestalls and headlocks at the feed manger will likely impact performance, since resting and feeding times will be reduced when stocking densities exceed 100 percent.

Recent research conducted at the Miner Institute in New York looked at stocking density.

The control stocking rate was 100 percent (1 cow per stall and per headlock).

The stocking rate was increased to 142 percent using three methods: by denying access to freestalls and headlocks, by denying access to freestalls as well as alley space and adding more cows. There were focal cows in each group that were used to record measurements.

Increasing stocking density to 142 percent decreased lying time from 13 hours per day for the 100 percent stocking rate to about 11.8 hours per day for the groups at 142 percent stocking rate. That might seem like a small difference in lying time, but small differences on dairy farms often make large differences in milk flow.

Feeding time of the focal cows was also reduced for two of the groups at 142 percent stocking density. Dry matter intake was not impacted significantly by stocking density, although numerically cows at 100 percent stocking density ate 55 pounds of dry matter while cows at 142 percent stocking rate ate 54 pounds of dry matter.

The authors suggested that cows in the 142 percent stocking density could have increased their feeding rate. Increased feeding rate might be similar to slug feeding. Regardless, group dry matter intake tells little about per-cow dry matter intake, because cows sort. Unfortunately, the authors did not report milk production.

A survey conducted by researchers in Spain, albeit with dairy farms with fewer cows than found on Western dairies, reported that number of freestalls and feedbunk management were important factors influencing milk production. It is difficult to separate these factors doing field work.

The researchers stated that overstocking may have had a negative effect on milk yield. The authors also speculated that with greater access to freestalls for longer resting times, cows will produce more milk.

The take-home message for the students in the dairy cattle production class was that stocking density impacts lactation performance.

Sure, it is a fine line and there are a lot of ifs and buts – however, there is adequate research information in the literature to say that stocking density impacts animal performance. There is also a bit of common sense.

Cows that have adequate space to rest and eat will likely produce more milk. Providing each cow with manger space and freestall space will have positive impacts on milk yield, cow health (feet and legs) and both profitability and sustainability of the dairy farm.

Providing cows with manger space and freestall space by reducing stocking density resulted in more milk production on the dairy farm – it was a common theme the dairy class heard this spring during their field-trip visits. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

DePeters is a professor in the University of California – Davis’ Department of Animal Science. Click here to contact him.