Of the approximately 9 million cows in the U.S., 16.4% were treated for this disease, or about 1.5 million mastitis cases treated annually.

In a Canadian study, intramammary administration of antimicrobials (IMM) accounted for 35% of all antimicrobial use on dairy farms, which was lower than systemic administration (38%). However, the amount of systemic drugs used to treat mastitis was not recorded, and systemic drug use included calves. Although antimicrobial therapy improves animal health and well-being, economic losses from additional labor and discarded milk can be considerable. Culled dairy cows account for 67% of residue violations among all marketed livestock in the U.S., and 83% of the residues in culled dairy cows were antimicrobial drugs.

To date, the risk of emerging antimicrobial resistance among bovine mastitis pathogens has been low, particularly for drugs with high therapeutic value in human medicine. Nonetheless, prudent use of antimicrobials is good for the farm and good for the public. Thus, it is important to know the basics of mastitis therapy.

Milk culture to identify the enemy

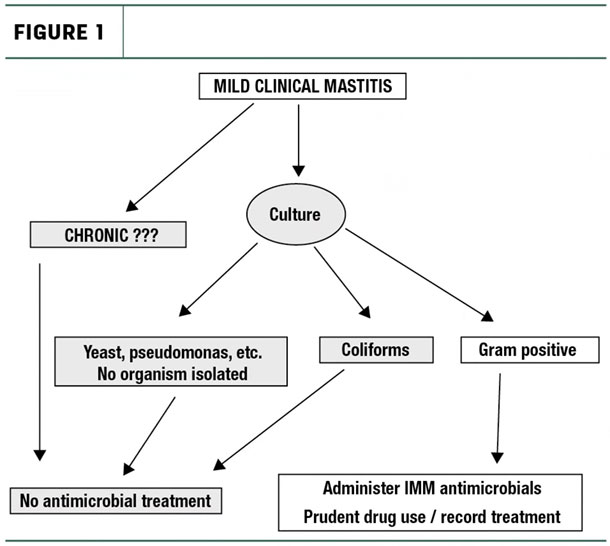

Microbial culture of milk is a practical tool to identify mastitis-causing bacteria. On-farm culture of milk before treatment of mild clinical mastitis cases reduces the percent of treated cows by 70% to 80%. This works because only cows that have cases caused by bacteria likely to respond to antimicrobials are treated. Typically, treatment is not given for 24 hours until results of milk culture are known.

Cows that do not yield a bacteria on culture or have a pathogen resistant to treatment (e.g., coliforms, gram-negatives, yeasts) are not treated. Not only does the 24-hour delay reduce antimicrobial use, but also this “wait and see” approach doesn’t cause any difference in long-term milk production, somatic cell count (SCC) or likelihood of a repeat case of clinical mastitis compared to cows treated without waiting for culture.

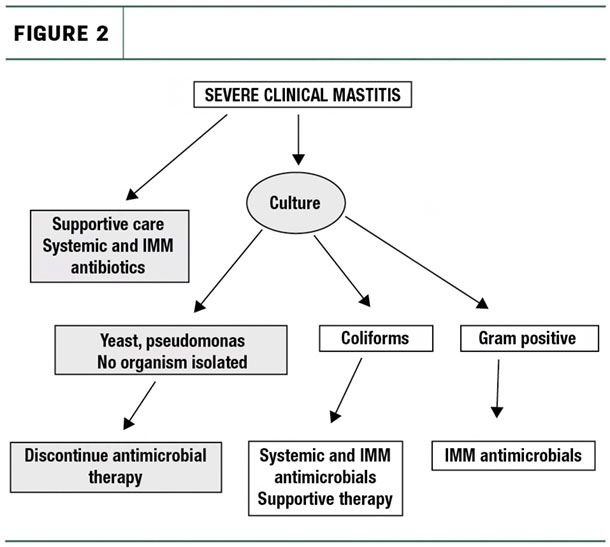

At the very least, milk samples should be regularly collected from a portion of clinical mastitis cases in a dairy herd to help guide therapy and also to target management for prevention. Examples of how to use milk culture in therapy decisions are shown in the flowcharts in Figures 1 and 2.

While culture of severe clinical mastitis cases should also be done when possible, therapy should be given immediately (not wait for culture results), along with supportive care, such as fluids.

Don’t treat repeat offenders (chronic mastitis cows)

Staying on course with a mastitis treatment protocol prevents any “cowside” biases in treatment decisions. That is, the protocol should limit the treatment of repeat offenders or identify those cows who are not likely to respond to therapy. Producers should “stay on the game plan” and not get creative with either repeat treatments or different drugs for that favorite cow. And yet, the majority of dairy producers report not having a written protocol, and extra-label drug use for the treatment of mastitis is common.

The efficacy of mastitis decreases for older cows, cows with high SCC and cows with chronic infections. Particularly, chronic infections are likely to have poor therapeutic outcomes and should be avoided. The best way to reduce the treatment of chronic mastitis is to maintain records of all cases that occur, including treated and untreated cases.

In the U.S., the majority of dairy herds only rarely culture milk samples from clinical mastitis cases. A Wisconsin study found that over half of clinical mastitis cases treated with IMM antimicrobials were caused by Escherichia coli or cases where no organism was isolated. Also, the majority of U.S. dairy herds do not maintain treatment records, or maintain only partially complete records. In Canada, treatment records were found to under-report antimicrobial use when compared to inventories of discarded vials and tubes. Thus, as in the U.S., records were incomplete on many Canadian herds.

Taken as a whole, the majority of farms across the U.S. and Canada may not consistently follow the practices that are critical for prudent antimicrobial use for mastitis therapy. Farms were as likely to use oxytocin or organic/natural formulations (15% to 20%) for clinical mastitis as they were to use bacteriology in treatment decisions.

The questions that should be answered before treating a cow with clinical mastitis are:

1. How severe is the mastitis case? A cow with systemic signs (septic/toxic), such as off feed, fever, dehydrated, decreased milk production, etc., will require immediate treatment that includes systemic antibiotic therapy, IMM therapy, supportive fluids and close monitoring – compared to a cow with mild clinical signs that are limited to the udder and milk.

2. Is this a new case of mastitis or a relapse? Repeated treatment of a recurrent case of mastitis is frequently unrewarding. If the recurring case of mastitis is to be treated, the therapeutic regimen might need to be extended beyond that of the previous treatment. However, no repeat case should be treated without the results of a milk culture from the affected quarter.

3. How many quarters are affected? The expense and the likelihood of treatment failure increases as the number of affected quarters increases. A cow with three or four clinical quarters may have immune system deficiencies, teat canal problems or an infection with an especially virulent or persistent bacterial strain – this is common for mycoplasma, for example.

4. Has the cow had a history of high SCC? Cows with a history of having a high SCC for three months or more are more likely to not respond to therapy, even if the clinical case is “new.”

5. Does the cow have other health problems? Other health problems such as metabolic stress (transition cow diseases), heat stress and hypocalcemia impair immune responses. The likelihood of successful mastitis therapy may be reduced in cows with concurrent illnesses. ![]()

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Ronald J. Erskine

- Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences

- Michigan State University

- Email Ronald J. Erskine

Barnyard pharmacology: Top 7 rules for more effective antimicrobial therapy

1. Clean teat ends completely before infusing mastitis tubes – otherwise you increase the risk for new infections.

2. Limit the volume of IM (intramuscular) injections to 10 milliliters – larger volumes alter drug distribution in the body and increase the risks for residues.

3. Don’t change the labeled route of administration – same reason as above.

4. More is not better; for most antimicrobials used in dairy cows, increasing the labeled dose will not increase efficacy.

5. If the label says shake well before use, do it.

6. Drugs do not distribute to all parts of the body equally. This is especially true for systemic drug use for mild mastitis. Most antimicrobial drugs labeled for dairy cows do not reach effective concentrations in the udder.

7. Follow a written protocol in consultation with your veterinarian.