While that seems like common sense, an objective look at drinking opportunities for cattle may lead to discovering ways to bring about better water utilization and, incrementally, more milk in the tank.

Adequate access, at the right time

According to Trevor DeVries, professor, University of Guelph, Ontario, cows will drink all times of the day, but the largest and most concentrated drinking events occur after milking and during major eating bouts. They will walk away from a meal to get a drink, but the entire group is eating at the same time and, consequently, drinking at the same time.

Just as humans may gather around the water cooler, cows may stand near the tank, waiting for a chance to drink. Social structure within the group may cause a timid cow to forgo a drinking opportunity in the presence of dominant cows.

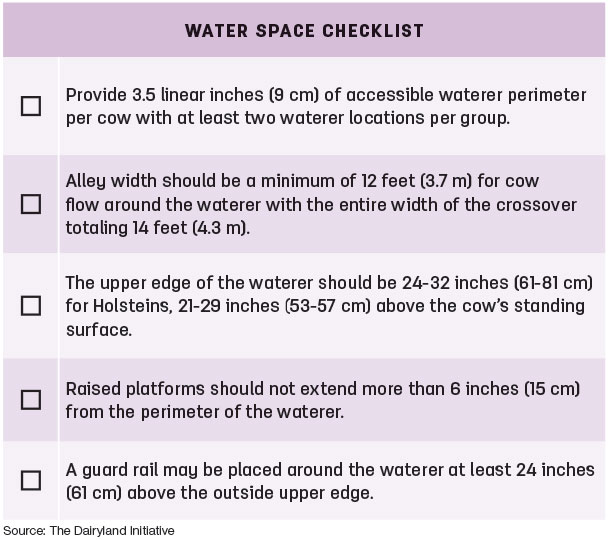

“Because a cow’s daily activities (milking, eating, drinking) are synchronized with other cows, water consumption becomes synchronized as well,” DeVries says. “She may only spend 10 or 15 minutes of the day drinking, but all the other cows are doing the same thing at the same time.” Cows will also spend about 30 minutes daily congregated in the alleys and crossovers surrounding waterers. At least two waterers at opposite ends of each group is the minimum standard, regardless of group size. Adequate space at each waterer is paramount (see Water Space Checklist).

In a field study of Canadian dairy herds, the average linear space was 2.8 inches per cow (range of 1.5 to 4.6 inches). According to DeVries, milk production increased by 1.5 pounds per cow, per day for every additional inch of linear space at the water trough.

“We could predict about a 4.5-pound-per-day difference in milk production between herds with low and high water space availability based on given water space availability,” he says.

Water intake expectations

DeVries says water consumption patterns in milking cows generally follow the lactation curve. In dry cows and especially close-up cows, adequate space and drinking opportunity becomes more important so cattle can continue to ingest and digest enough feed to keep transitions into lactation as smooth as possible.

Heat stress causes cows to decrease water intake, one factor in decreased milk production during heat stress. Decreased water consumption can also cause harm to both the calf and close-up cow upon calving.

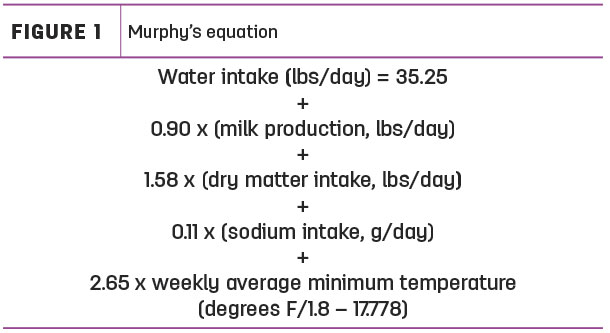

Water intake needs required during various lactation stages are determined using the industry-standard Murphy Equation (Figure 1).

The formula adjusts for dry matter intake (DMI), stage of lactation, sodium intake and daily temperature.

Water quality – cleaning and testing

Water quality is another location where management might fall short.

“We have come a long way in keeping waterers clean and without slime,” Dr. Luciano Caixeta, DVM, University of Minnesota, says. “Regular maintenance and cleaning is just common sense. You wouldn’t want to drink brown, bad-smelling water. A professor used to challenge us to keep the water tanks clean enough to drink out of them ourselves.”

Water quality and composition within the groundwater supply can impact flavor and even cow health, and it should be tested to obtain a baseline documentation of elements or potential water contaminants.

Mike Socha, research and product development leader, Zinpro Corporation of Eden Prairie, Minnesota, says at a minimum, a water quality test should determine levels of calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, chloride, manganese, iron, sulfur, copper, potassium, bacteria, total dissolved solids and pH. This test will cost $50 to $70.

“If there is any type of mining in the area or proximity to old orchards, or if you have had a leaking fuel tank or any type of pesticide spill, have sandy soils or a high water table, then invest the extra money into a comprehensive test that checks for fluoride, lead, herbicides, pesticides and arsenic,” Socha says. “Especially if you are in a mining area, even if they are mining for sand, they may stir up ground or have some sort of spillage. Then do routine (every six months) water sampling and spend the extra money. Then you have documentation and have ground to stand on if you would ever end up in court.” A comprehensive sample Socha described generally costs $400 per sample.

“My understanding is: Cows have a fairly sensitive taste system,” Socha says. “My experience is: High levels of sulfate, iron or manganese in the water – those tend to give the water a bitter taste. Copper would be another. I haven’t had much trouble with calcium, but when magnesium is high, we tend to see cows just aren’t milking well, production is down a little bit, and they seem to have a lot of health issues.”

Rotten egg smell – hydrogen sulfide – is lost before it can be lab-tested and must be tested at the wellhead using test strips. He warns that correct calibration is necessary when chlorinating or treating with hydrogen peroxide because overtreating can cause imbalanced rumens.

Socha encourages the more thorough sampling in the following scenarios: Water color is off due to tannins (which cause a faint yellow or tea-like color) or turbidity (large number of particles causing cloudiness), shallow groundwater or if ponds are used for watering.

“Based on my experience, there is equipment that works great and equipment that doesn’t work at all to filtrate water,” Socha says. “When sulfate or chloride is the problem, reverse-osmosis systems are needed; if iron or manganese are the issue, oxidation or chlorination treatment followed up with a filter works. You can get some really nice improvements in animal health with the right equipment on the farm to treat the water, but one piece of equipment is not going to work for every situation. You have to have the right treatment.” ![]()

PHOTO: Don’t let water be the limiting factor in achieving milk production goals. Provide access to water at peak consumption times and routinely test for minerals, bacteria and pH to encourage drinking. Photo by Mike Dixon.

Bev Berens is a freelance writer in Holland, Michigan.