Lactobacillus this … Pediococcus that … Enterococcus another thing … Sounds to me like a repeat of the old Abbott and Costello baseball routine, “Who’s On First?” Remember, “Who’s on first? What’s on second? I don’t know … third base.”

In the world of both disease-causing (pathogenic) and beneficial bacteria, the nomenclature can become very confusing extremely quickly, so much so that we can easily say like Abbott and Costello, “I don’t know … third base.”

A simple review of the taxonomy of the micro-organisms, specifically bacteria that we deal with on a daily basis, is probably in order. Genus, species, sub-species, strain – this is the way it was presented and the way we learned it back in middle school or junior high school.

Lactobacillus, Pediococcus and Enterococcus are genera (plural of genus) of bacteria. Taken one step further, not all Lactobacillus are of the same species, as there are buchneri, plantarum and the most easily recognized, acidophilus.

But this only serves to delineate these organisms at the level of species. Can we further separate them in a more meaningful manner?

Taken another step further, not all Lactobacillus acidophilus are the same, just like not all Lactococcus lactis are the same. Sometimes there are subspecies designations that help us to separate species into more homogeneous groupings of subspecies.

A nearly perfect example of subspecies designations can be found in the dairy industry’s experience with Johne’s disease, more specifically Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis.

In several instances, a particular genus and species of bacteria does not have or warrant a subspecies designation, but that doesn’t mean that strains don’t matter. Bacteria strains matter.

Maybe an example outside the microbiological realm would serve as a good example of the concept of strains. Let’s look at this concept in the world of cattle.

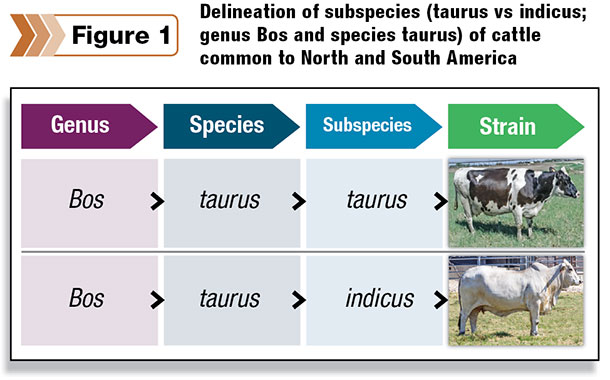

Figure 1 shows the genus, species and subspecies of two common cattle breeds. Both breeds are of the genus Bos and the species taurus, but they differ in their subspecies, taurus versus indicus.

At the subspecies level, would you rather have a milking string of Holsteins or Nellore? Obviously, differences at the subspecies level matter.

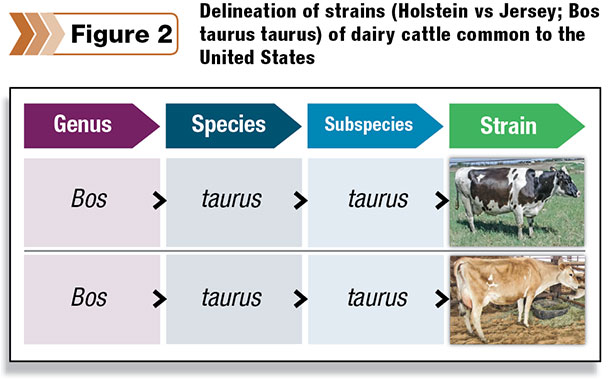

That’s a fairly extreme example of subspecies differences, but what about strain differences? Staying with the cattle theme, Figure 2 shows a more realistic example of a strain difference. Both Holsteins and Jerseys are quite popular in the U.S. and around the world for a variety of reasons.

These breeds belong to the genus Bos, species taurus and subspecies taurus. Just like our formal designation for Johne’s disease, Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis, classical dairy breeds can be designated, Bos taurus ssp. taurus. We could argue this next question for the next 100 years, but would you rather milk Holsteins or Jerseys?

These breeds belong to the genus Bos, species taurus and subspecies taurus. Just like our formal designation for Johne’s disease, Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis, classical dairy breeds can be designated, Bos taurus ssp. taurus. We could argue this next question for the next 100 years, but would you rather milk Holsteins or Jerseys?

Same genus, species and subspecies – but significantly different strains. Dairy cattle strains matter, why wouldn’t bacteria strains matter? The answer is: clearly, they do.

Think about disease-causing bacteria like E. coli. There are five broad classifications of E. coli, and only some of the classifications cause disease. There are numerous E. coli in your digestive tract right now, and unless you are currently experiencing digestive distress or a mild digestive upset, then they are not the disease-causing strains.

The most obvious example of a disease-causing strain of E. coli is O157:H7. This strain generally occurs as some sort of food poisoning, leading to digestive distress, diarrhea and possibly even death. Do bacteria strains matter? Absolutely.

The cattle and E. coli examples of strain differences only serve to strengthen our next point. In the realm of bacterial silage inoculants and probiotics (direct-fed microbials) that are often used in a dairy operation, strains matter. Not all Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus buchneri, Pediococcus pentosaceus and Enterococcus faecium are the same.

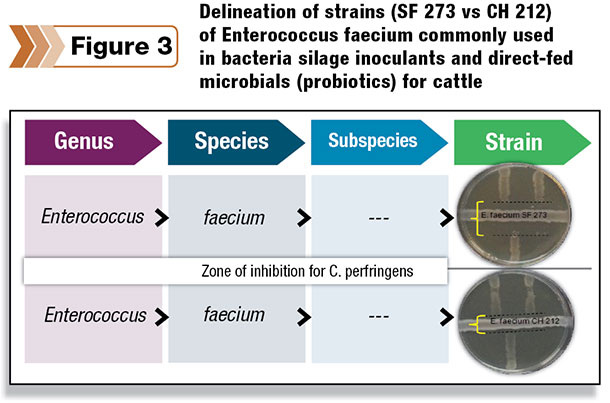

Figure 3 shows a very simple example of strain differences within the species Enterococcus faecium and their ability to inhibit a pathogen.

The pathogen, Clostridium perfringens, can cause a variety of digestive disturbances, like overeating disease in sheep, and has been implicated in hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle.

Two different strains of E. faecium (SF273 top and CH212 bottom) were streaked through the middle of a petri dish with Clostridium perfringens plated in perpendicular streaks.

In rather simple terms, the zone of inhibition (indicated by the yellow brackets) is different for the two strains; specifically, SF273 (DSM 16567) is better at inhibiting C. perfringens than is CH212 (DSM 16573).

They are both Enterococcus faecium, but they are different strains, as noted by their unique deposit numbers (within the international DSM depository), performing different tasks with differing efficiency and effectiveness.

Bacteria strains can differ significantly in traits such as tolerance to oxygen, salt and bile, optimum and terminal pH, range of temperature for optimum growth, oxygen scavenging – and the list goes on.

As discussed in the previous examples, they may differ in their fermentation outputs – for instance, acids, enzymes and expression of peptides inhibitory to other micro-organisms. These and many other traits are extremely important when selecting organisms for use in silage inoculants and as probiotics.

Once the organisms (bacteria) are selected, they are deposited in central strain banks. Strain banks are independent depositories that hold bacteria strains for “safe keeping.”

They are integral for preserving the original strain and maintaining identification and purity. These strain banks also serve a vital function when it comes to a company’s need to support registration and regulatory requirements for various countries or regions globally.

Dairymen are naturally informed skeptics when it comes to purchasing and using bacteria products, like silage inoculants and probiotics, and have become more discerning in their analysis of the economics and research data provided by manufacturers and distributors.

But just as important as the question of “Can I see your research data?” are the questions of “Can I see your research data on your specific strains of bacteria?” and “How are your strains of a particular species of bacteria superior to your competitors’ strains?”

Although Abbott and Costello didn’t know who’s on first or what’s on second and concluded, “I don’t know … third base,” we now know that bacteria strains matter, just like the breeds of dairy cattle we choose to milk daily. PD

Keith A. Bryan is a global technical portfolio manager of silage inoculants and cattle probiotics for Chr. Hansen Animal Health and Nutrition Commercial Development.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Chris J. Rhoden

- Sr. National Accounts Manager

- Chr. Hansen Animal Health and Nutrition

- Email Chris J. Rhoden