Lameness, tetracycline residues and common foot ailments were among the trending topics at the 2014 Hoof Health Conference. University experts, including Dr. Chuck Guard from Cornell University, Dr. Nigel Cook from University of Wisconsin – Madison and Dr. Gerard Cramer from University of Minnesota, shared their research and observations with an international audience of hoof health professionals gathered in Brookfield, Wisconsin, in July.

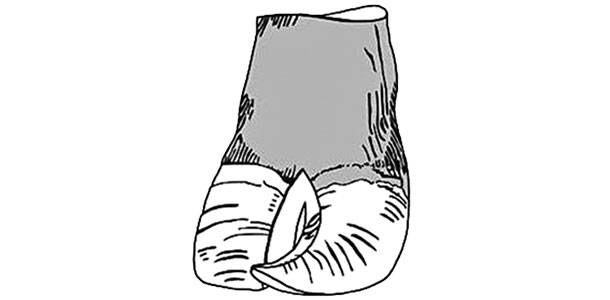

Return of the corkscrew claw

Dr. Chuck Guard led an open discussion with hoof trimmers regarding what they are seeing in the field. He noted that the corkscrew claw is making a comeback. Recalling his early days of veterinary practice, he would occasionally see cows with “twisted toes,” but that “kind of disappeared” until sometime in the last decade.

“[Corkscrew claws] are everywhere now,” Guard stated.

Another trimmer affirmed, saying, “It’s getting to be an epidemic. It doesn’t matter if they are registered or commercial herds.”

It is debated whether the increased incidence of corkscrew claw is genetic or environmental. Guard speculates that it is an inherited trait, particularly if it is found symmetrically in multiple toes. Through his cadaver feet studies, he has observed that cows with this condition simply have different pedal bone structures than normal cows. “It’s just the way they are made,” he said. “There is not necessarily damage to the corium or fat pad.”

Another phenomenon Guard has noticed are sole ulcers occurring farther back into the cow’s heel. Most commonly, he has seen this on the inside rear toe of cows that go out to pasture. He has yet to reach a rational mechanical explanation for this injury.

How high-producing herds handle lameness

According to Dr. Nigel Cook, achieving a high level of herd performance and controlling lameness go hand-in-hand.

“You cannot manage your herd successfully unless you manage lameness,” he said. “It undermines everything you try to do. It impacts the way the cow behaves, the way she walks, the way she eats, the way she rests. It impacts reproduction and increases the risk for early removal.”

In a survey of 22 intensively managed, high-producing commercial dairies, Cook compared lameness prevalence to that of cows kept primarily on pasture.

“They averaged 13 percent of cows walking with a limp,” he stated. “That’s on par with a lot of grazing herd surveys.”

These elite herds were taking similar strides to manage lameness:

- 70 percent used deep, loose sand bedding

- 58 percent trimmed at least twice per lactation

- 50 percent trimmed heifers prior to calving

- Average foot bath use: 4.5 times per week

- Each had a sufficient number of trained employees regularly observing cows for lameness

- Several offered pasture or dirt access for some period of time

The benefits of deep, loose bedding cannot be denied. Lame cows struggle with the transition from standing to lying, and vice versa. A stall surface like sand provides comfort and traction as the cow rises or lies down.

While great for cow comfort, sand can cause significant wear on the hooves, and that is something trimmers need to keep in mind.

“We have to adapt to the situation,” Cook explained. “If we do not recognize that and have excessive wear, and we come in with grinders and take off too much sole and shorten the toe even more, then it’s a disaster.”

In herds with excessive wear, he advises trimmers to not touch the inner claws. Likely, they are overworn. Instead, focus on shortening the toe when possible and balancing the claw. However, he warns, “If you balance an outer claw to an already worn inner claw, you just made things a whole lot worse, not better.”

Regular hoof trims timed with the cow’s stage of lactation also prevented lameness.

“Trimming at least twice per lactation or more is becoming commonplace,” Cook said. He has observed the mid-lactation trim occurring earlier, at 60 days in milk (DIM) instead of 150 DIM. Most cows are also trimmed at dry-off, but astute herds are identifying groups of cows that need one more trim prior to the end of their lactation.

Cook believes that some amount of pasture access is something freestall herds “need to build into their production systems.” Data indicates it is beneficial for lameness and can be done without a huge production hit.

Milk residues and tetracycline use

The “go-to treatment” for digital dermatitis could soon be regulated, noted Dr. Gerard Cramer.

The FDA added the drug tetracycline to its “highly important to human medicine” list. According to Cramer, “This likely means, but not guaranteed, that tetracycline is going to become a prescription-only drug.”

Because tetracycline is not presently labeled for the treatment of digital dermatitis, there is no specific dosage or milk or meat withholding time after a cow receives treatment. If it were to require a prescription, that means the dairy’s veterinarian assumes the risk when determining how much tetracycline the hoof trimmer can apply, how it can be applied and the withdrawal period.

The threat of tetracycline residues ending up in the bulk tank is one for dairy producers to take seriously. While the legal limit for the drug in milk is 300 ppb in the U.S. and 100 ppb in Canada, there are processors running tests that can detect as little as 10 to 30 ppb – and by some of their standards, that could mean rejecting a load of milk.

With these concerns in mind, Cramer conducted a research study to determine how much tetracycline trimmers are applying and whether or not it may be contaminating the milk from treated cows. His treatment groups included tetracycline applied with either wraps or paste and in the amounts of 2 g, 5 g and 25 g per foot.

Of 213 milk samples, 21 had detectable levels of tetracycline, with the highest being 63 ppb. Most of these occurred within eight to 27 hours after treatment. In the group receiving wraps with 25 g of tetracycline, every single cow treated had at least some residue in her milk at some point following the application, though these numbers were under the legal limit.

From this preliminary data, Cramer plans continued research to determine whether the residues are in the blood or on the teat surface that may have contacted the tetracycline.

In the meantime, Cramer advises trimmers to be cognizant of how much tetracycline they are applying. It is likely that some amount is absorbed into the cow’s system, thus he suggests minimizing tissue damage during trimming because an open wound increases the chance of absorption. Also, be aware that applying high doses increases the risk of triggering a screening test, especially within small herds. PD

Peggy Coffeen

Editor

Progressive Dairyman