Every case of mastitis is costly to the dairy producer. It may be in terms of decreased milk production, treatment expense, lower milk quality premiums and possible culling or death of the affected animal. Indirectly, it takes extra time during milking to properly identify a treated cow and discard her milk, and there is always the risk of antibiotic residues if a treated cow is accidently milked into the tank.

One frustrating aspect of mastitis treatment is repeatedly re-treating a cow that relapses with an infection in the same quarter multiple times. These “subclinical” infections result when a producer discontinues antibiotic treatment because the milk looks normal, but the hard-to-kill mastitis organisms are still alive in the gland and waiting for their opportunity to attack again.

Extended-duration intramammary therapy (“extended therapy”) increases the chance of complete bacteriological cure of mastitis in which all of the bacteria in the gland causing the infection are killed. Complete cure often prevents relapses and will help prevent further damage to the mammary tissue, lower somatic cell count and sustain future milk production.

The bacteria that commonly cause mastitis are classified into contagious organisms transmitted cow-to-cow during milking and environmental organisms acquired from the cow’s environment.

Historically, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae, both considered contagious organisms, were the most common causes of mastitis in dairy cows and responsible for nearly 90 percent of infections. Consequently, most drug therapies were targeted to kill only those two organisms.

However, within the last 10 years, the predominant problems have shifted to environmental bacteria because dairies have successfully corrected the contagious mastitis problems through better milking procedures in the parlor.

Currently, the most commonly cultured organisms from mastitis milk include Escherichia coli, Streptococcus uberis, Streptococcus dysgalactiae and coagulase-negative staphylococci – all considered environmental “bugs.” These bacteria require different antibiotic therapy than the contagious organisms to achieve complete cure.

It is important to realize that mastitis-causing bacteria will change on a farm over time. For example, changes occur between seasons, when new cows are added to the milking string or as a result of mastitis control strategies implemented during milking.

Therefore, routine culturing of milk from mastitis cases will help to identify the current disease-causing bacteria and to make the crucial changes necessary for effective treatment and prevention of new cases.

An extended-therapy protocol or extended duration of therapy is one of the most effective treatments against the environmental organisms frequently encountered in mastitis cases today. It is also one of the few effective treatments against Staphylococcus aureus mastitis that is often the culprit in stubborn cases with an extremely high SCC.

Simply defined, extended therapy is administering intramammary treatment (mastitis tubes used in the quarter) for two to eight days consecutively. Only two products on the market (Spectramast and Pirsue) are labeled for and demonstrated effective with extended therapy.

Both products are available by prescription only, so a valid veterinary-client-patient relationship must exist to obtain these medications. However, extended therapy is not “extra-label” – in other words, a producer can follow the label directions on the box instead of the veterinarian needing to write special or alternate directions for use.

Spectramast LC (ceftiofur hydrochloride) is labeled for treatment of clinical mastitis due to three environmental organisms: coagulase-negative staphylococci, Streptococcus dysgalactiae and Escherichia coli. “For extended-duration therapy,” the label reads, “once-daily treatment may be repeated for up to eight consecutive days.”

Pirsue (pirlimycin hydrochloride) is labeled for clinical and subclinical mastitis due to the contagious organisms Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae, and the environmental organisms Streptococcus dysgalactiae and Streptococcus uberis.

The extended therapy directions state to infuse one syringe into each affected quarter and daily treatment may be repeated at 24-hour intervals for up to eight consecutive days.

When pirlimycin is used daily for up to eight days, it is important to use it only in the quarters known to be infected and not treat uninfected low-SCC quarters of the same cow.

The product insert specifically warns that even with adequate teat-end preparation and sanitation, extended therapy can sometimes result in elevated somatic cell counts or clinical mastitis that is most often due to infection with gram-negative environmental organisms.

If acute clinical mastitis (visibly abnormal milk) or other clinical signs of illness (fever, redness, swelling of the quarter) develop during extended therapy with pirlimycin, discontinue therapy immediately and contact your veterinarian.

Residue warnings for milk taken from animals during treatment and for 36 hours after the last treatment must not be used for food. Pre-slaughter withdrawal is nine days if infused only twice in a 24-hour interval but is 21 days if extended therapy is used.

Recently, a systematic review of all of the relevant individual studies performed worldwide was undertaken to help veterinarians and producers choose the best antibiotic therapy to use during lactation against Staphylococcus aureus.

Based on this review and all available data, the best option was found to be extended intramammary therapy for five to eight days with pirlimycin. There was no evidence to support the use of injectable antibiotics at the same time as intramammary therapy (mastitis tubes used in the quarter) to increase cure rates.

Work with your veterinarian to determine which cows would benefit from extended therapy and how many days of treatment are recommended to achieve complete cure.

In summary, the benefits of extended therapy include:

- Higher proportion of bacteriological cure caused by common mastitis organisms

- Reduced chance of relapse and treatment failure

- Decreased SCC

- Less risk of spread of contagious organisms, especially Staphylococcus aureus

- Improved marketability of milk

The drawbacks of extended therapy include:

- Price of the medication (antibiotic tubes)

- Loss of milk due to long treatment duration

- Risk of residues in milk and meat

- Potential to develop more mastitis due to repeated infusions – this is especially true with extended use of pirlimycin.

It is crucial to work with your veterinarian to first determine what organism is causing mastitis in order to choose the most appropriate drug and duration of antibiotic therapy.

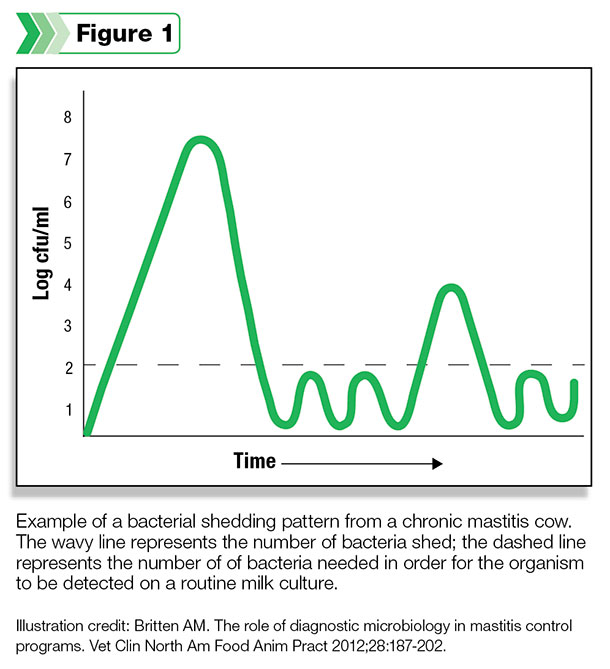

A milk culture may be performed to grow and identify the organism in a laboratory and determine the most appropriate antibiotic for treatment. Unfortunately, for the culture to detect a mastitis organism, there must be a minimum number of bacteria present in the sample.

Shedding rates vary widely, and S. aureus is one bacteria that frequently shows low or intermittent shedding rates (below the detection limit). A “no growth” laboratory result could mean the cow has recovered, or she may be shedding bacteria below the detection limit but still has the disease (Figure 1).

One tactic to compensate for this problem is simply to repeat the culture, especially in cows with persistently elevated somatic cell counts.

Although this may seem like a waste of money and time, ultimately culture results are invaluable to identify the important contagious mastitis organisms, including S. aureus, S. agalactiae and Mycoplasma. Healthy cows must be protected from exposure to contagious mastitis pathogens or they risk new infections, high somatic cell counts and further spread of disease.

Working with your veterinarian to determine what type of mastitis you are dealing with combined with the knowledge of the individual cow age, lactation status, treatment history, SCC, length of infection and overall health status will ultimately lead to the best treatment decisions on your farm.

Extended therapy may prove very helpful in eliminating bacteria that are difficult to cure through traditional treatment protocols and preserve milk production in valuable cows. Ultimately, antibiotic therapy should be reserved for cases most likely to benefit from it.

Cows late in lactation and not pregnant, sick, chronically lame or not producing much milk should be considered potential culls rather than treatment candidates.

—Excerpts from Kentucky Dairy Notes and Southeast Milk Quality Initiative newsletter