Mastitis is one of the most common diseases affecting dairy operations as a detriment to cow comfort and, ultimately, profitability. Traditionally, dairymen have relied on a five-point plan to control the disease that focuses primarily on sanitation and proper treatment of the herd. But Dr. Stephen C. Nickerson, head of the Animal and Dairy Science Department at the University of Georgia, thinks there is one area that deserves greater consideration.

“One potential mastitis management practice that has been overlooked is fly control,” said Nickerson.

“And with the new somatic cell count (SCC) legal limit of 400,000 cells per milliliter looming in the very near future, every attempt to reduce animal stress and the development of new intramammary infections is warranted, especially during the hot summer months when fly populations are at their peak.”

Horn flies are a leading cause of intramammary infections in cows as they bite the animals to feast on their blood.

When a heifer’s teats have been bitten, they will develop many scabs containing bacteria that can develop into disease, most commonly mastitis.

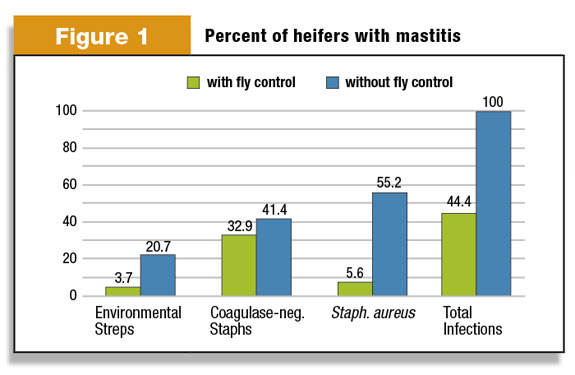

Supporting his case for fly control, Nickerson cites a survey performed by Louisiana State University. The survey found that dairy herds using fly control produced significantly lower numbers of mastitis infections than similar dairies applying no fly control.

The discrepancy was greatest with the Staphylococcus aureus bacterial species, the most common cause of mastitis, which was found in 55.2 percent of untreated cows but only 5.6 percent of those in treated herds.

According to Nickerson, dairies that combine various fly control methods with a proper integrated pest management (IPM) program can see a significant reduction in cases of mastitis. IPM is a pest control strategy that uses an array of complementary methods including natural predators and parasites, cultural practices, biological controls, various physical techniques and insecticides.

Proper sanitation practices, such as cleaning up spilled feed and preventing manure buildup around barns and fences, will eliminate breeding sites for these flies. Adult flies can also migrate from other areas and may require the use of on-animal and premise insecticide applications and/or the use of traps and baits to control them.

Feed-through insect growth regulators are relatively new to the market and have become a highly recommended component of any IPM program to be used in conjunction with insecticides. These feed supplements can prevent house, stable, face and horn flies from developing in and emerging from the manure of treated cattle.

Unlike conventional insecticides that attack the nervous system of insects, feed-through regulators can interrupt the fly’s life cycle, rather than through direct toxicity. When mixed into cattle feed, they pass through the digestive system and into the manure.

With only very small concentrations, they can disrupt the normal molting process of the fly larvae, disrupting the production of a substance called chitin, a key component of an insect’s exoskeleton that is not found in mammals. Without a properly formed exoskeleton, the immature fly cannot survive to adulthood.

The best way to address a specific fly problem is to identify the exact species affecting one’s herd and understand the various life cycles. Biting and non-biting flies alike can be responsible for intramammary diseases like mastitis, and all flies can act as a nuisance to a dairy’s employees and cattle. The most common species found among dairy cows include:

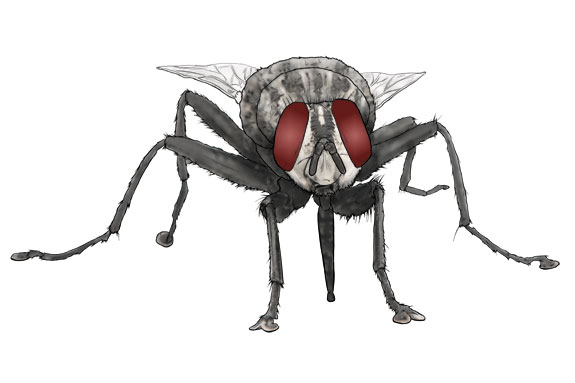

House fly

• Nonmetallic, dull grayish-colored flies, approximately six to seven millimeters in length with four distinct stripes on their thorax

• The abdomen is usually a pale color with yellowish sides and underside

• Female house flies lay one-millimeter long, slightly curved, whitish-colored eggs that are normally deposited in batches of approximately 150 eggs in manure, wet organic matter, spilled feed, compost piles, decaying fruit and various other potential larval development areas

• The white larvae hatch within 24 hours and feed on waste, eventually migrating from the food source to pupate in drier areas

• The pupal stage lasts anywhere from three to 10 days, with the emerging adults beginning feeding within 24 hours

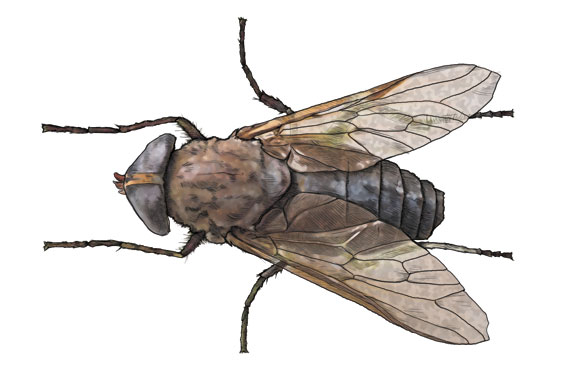

Stable fly

• Close in size to the house fly with similar stripes on their thorax, but with a distinct “checkerboard” pattern on the abdomen

• Approximately one millimeter in length with distinct piercing mouthparts to pierce the host animal’s skin

• They are usually laid in masses of up to 50 eggs, hatching within one to three days

• Larvae prefer fecal material that has been mixed with soil, straw, bedding material, silage or grain, but will also develop in wet grass clippings, silage and poorly managed compost piles, migrating to drier areas to pupate

• New adults will emerge within six to 26 days, with the entire life cycle taking three to four weeks

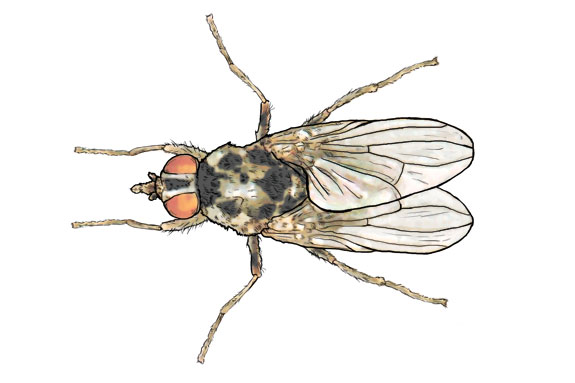

Face fly

• Face flies resemble the house fly, but may be slightly larger and grayish in color

• They have four stripes on the thorax and sponging-type mouthparts like the house fly for feeding on secretions around the eyes, nose and mouth of cattle

• Males have abdomens that are yellowish-orange in color

• They lay eggs only on fresh, undisturbed cattle manure and are primarily considered a pastured cattle pest

• Larvae hatch from the eggs and feed under the dung crust, dispersing in surrounding soil to pupate once fully developed

• In the fall, newly emerged adults go into diapause to delay reproduction until the following spring; often found in large numbers in attics of buildings

Horn fly

• Small, biting flies about half the size of house and stable flies

• Grayish in color with two stripes on their thorax and usually found congregating on the backs of cattle

• They have piercing-type mouthparts and can take up to 40 blood meals per day

• They lay their reddish-brown eggs in freshly deposited cow pats, which then hatch and feed in the manure pat and pupate underneath or in the surrounding soil around the pat

• Pupae are brown and require six to eight days to pupate

Each fly presents a unique set of problems for a dairy operation, but a proper control effort can significantly lessen the impact. By identifying the pests affecting the dairy and implementing a complete IPM program, dairy operators can help keep cows comfortable, healthy and profitable. PD

Mark Taylor is the business manager for the Professional Agriculture Division of Central Life Sciences. Click here to contact him for more information.

PHOTOS

TOP RIGHT: A healthy udder

MIDDLE RIGHT: ComparIson to an udder with scabs at high risk for mastitis. Photos courtesy of Mark Taylor.

Mark Taylor

Business Manager

Central Life Sciences