For decades we have been sending sick or special-needs cows to the hospital pen, assuming this is a safe place for them. But how much of this is true? Are we actually helping these animals or making their life worse and riskier? How is this long dairy recession affecting the health of our animals? I will share my experience about the actual situation for hundreds of different herds in the U.S. It will show you how with little or no money at all, common sense and employee training in basic equipment maintenance and sanitation, you can make the hospital pen a healthier place for your cows to be.

The situation

I was invited to a dairy farm in southwestern Idaho because they had an unusually high number of cows in the hospital. After asking a few questions and doing some laboratory testing, we confirmed that Mycoplasma was the cause of this mastitis outbreak. We know that this pathogen (and other contagious bacteria) move among lactating animals in the herd, primarily during the milking process.

As part of a plan to act on the disease, I scheduled a hospital management and sanitation assessment to check on the hospital parlor, the milkers and their procedures. What I saw during my assessment is not different from what I’ve seen in many other parlors in different parts of the U.S. Even the best-managed hospitals will benefit from a periodic evaluation and a review training session to fine-tune the process of managing these hospital cows and facilities. Most of the basic sanitation and maintenance principles that we use in the hospital should also be applied to the regular milking barn.

Many factors affect mastitis rate on a farm. When I walk into a parlor, I focus on the milking machine, operators, milking routine and their interaction with the cows. Some publications attribute up to 20 percent of new intra-mammary infections to milking equipment factors. I suspect in many of the facilities where I have worked, this percentage is even higher.

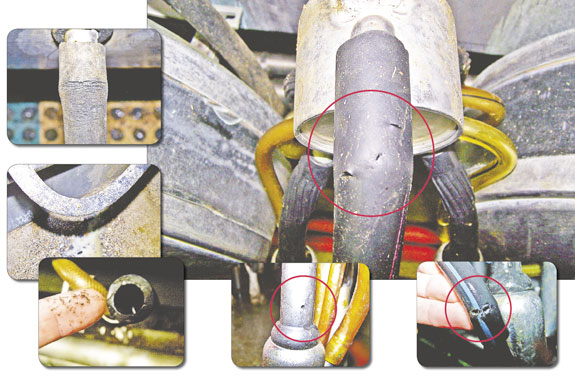

When I inspect the machine, the most frequent problem I see is the deterioration of rubber parts. With time and the action of washing and sanitizing chemicals, the surface of the rubber turns from shiny and smooth to rough and cracked. These cracked surfaces are hard to clean and can harbor mastitis-causing bacteria, increasing cow exposure to mastitis pathogens. I find holes in the rubber goods in almost every barn I visit.

Short-air tubes and liners are the most commonly affected, followed closely by the milking hoses. I like to visually inspect and feel the twin air hose with my hand to make sure the pulsators are working. Milk or water moving up and down the twin hose with each pulsation cycle is an indication of a problem. Usually a broken liner or twin hoses that are too loose is the cause.

The ear test is simple and quick to perform on a daily basis by the milkers and can give very important information about pulsator function and air leaks without using an electronic vacuum recorder. With the pulsators on, the operator listens for two to three seconds through the mouthpiece of two liners in each claw, comparing side to side or back to front, depending on the system. This test should complement but never replace the pulsator checks performed by a qualified technician with a vacuum recorder.

Holes in the rubber may cause vacuum fluctuation and inappropriate liner movement during milking, which leads to incomplete milking, inadequate massage to the teat with consequent teat edema and possible damage, therefore increasing the chances of mastitis. If you are using vented liners, make sure all the liners have their vents. A quick check at the beginning of each shift and during milking is required because the air admitted in the claw by the bigger hole when the vent is not in its place is much higher, and can reduce claw vacuum and generate turbulence in the claw during milking. Clean or unplug regularly the holes in the vented claws to allow correct milk flow.

I like to listen to the milkers’ opinion on how the system is working and how the cows are milking. Very few of them mention they’ve received any training on how to care for the machine. Most of them don’t believe it’s their responsibility at all.

The plan

I proposed to the owner that he make every employee at the farm a Mycoplasma expert. We added some quick and easy machine checks to their milking routine, just like you check the oil and gas in your car before a long road trip. We designated a lead person in charge of that shift’s equipment cleanliness and rubber maintenance.

The owner bought a cabinet for the break room where we stored the new rubber goods, accessible to everybody. We marked on the milkers’ requested days-off calendar, all the scheduled changes for hoses for the year for the main barn and hospital barn.

I met monthly with the producer and workers to review the new program’s progress. The new cases of Mycoplasma mastitis and transmission in the hospital cows were reduced dramatically after the first two milkers’ meetings. This reduction, coupled with milk culture and cow culling, was enough to stop the outbreak.

Quick basic maintenance and sanitation checkpoints for producers:

• Train your milkers to know their responsibilities in the parlor.

• Involve them in quick everyday machine maintenance – check rubbers, ear test.

• The milkers should keep the equipment clean and disinfected at all times to reduce cows’ exposure to bacteria. Pressure wash or scrub the system with soap and disinfectant at least once a day after milking.

• Producers should provide access to spare rubber parts as needed.

• Schedule with your regular service provider a change of all rubber goods that is appropriate for your farm.

• I like to see the milk hoses, jetter cups, duck bills, and twin air tubes changed every six months. The short pulsation tubes and liners should be changed after about 1,200 to 1,500 milkings (silicone liners last longer).

Independently from the economic situation the dairy is going through, some things seem to always be overlooked and never make it on dairyman’s priority list. These few quick maintenance checkpoints are just the first steps to move in the right direction if you decide to make the hospital in your dairy a better place for your cows to be.

As dairy farms grow bigger, you’ll have to delegate responsibilities and trust more in your employees to manage your cows safely and efficiently to improve your bottom line. They are your eyes in the field and investing a little money and time training them to do the right thing can make the difference and pay back enormously. PD

PHOTOS :

TOP RIGHT: We added some quick and easy machine checks to their milking routine just like you check the oil and gas in your car before a long road trip.

TOP LEFT: Even the best-managed hospitals will benefit from a periodic evaluation and a review training session to fine-tune the process of managing these hospital cows and facilities. Photos by Damian Lettieri .

-

Damian Lettieri

- Veterinarian

- Udder Health Systems

- Email Damian Lettieri