By now most have heard the comparison made between a dairy cow and an Olympian. Many articles have described the cow as a bovine athlete, secreting high volumes of milk with an ever-increasing percentage of milk solids.

But can this metabolic marvel be encouraged to be more efficient? Are we able to get our cattle to perform on the level of some of the greatest athletes known? One secret may lie in Muhamad Ali’s old proverb, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

In the nitrogen nutrition realm of the dairy industry, dietary crude protein is the go-to indicator for the overall nitrogen content within a given ration. But fallacies exist and bias emerges when using crude protein as a proxy for nitrogen status.

Because each amino acid has its own percentage nitrogen which makes it up, and the amino acid profile for a given feed or forage may be different from one another, the assimilation of every amino acid into a generalized crude protein can either over or under-predict the nitrogen in a given diet.

For most of this century, the swine industry has moved away from crude protein as a way to measure nitrogen requirements. Instead, nutritionists are formulating diets using gram amounts of amino acids within the feeds consumed by the animal. With decades of research on growth requirements and nutrient supply, this practice is far from a guessing game.

A quick glance at the Nutrient Requirements of Swine, the National Research Council’s publication on swine nutrition, and you’ll find page after page of tables describing rates of gain, intestinal digestibility, and energy density of diets for various stages of life, all broken down into individual amino acids for easy access. The swine industry has nitrogen nutrition down to, quite literally, a science.

So where does that leave us, the dairy industry? One may point out the obvious digestive differences between a cow and a pig. With the rumen typically supplying half of the cow's protein requirements, it does present unique challenges in amino acid balancing that our swine brethren never need to think about. But there are ways to deal with this.

With advancements in technology and improvements in feed characterization and animal requirements, the industry can move closer to balancing on an amino acid level. Efforts have been made in recent years to revamp The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) to calculate protein metabolism and amino acids on a nitrogen basis rather than using crude protein as a proxy.

By capitalizing on the dynamic structure and iterative time steps of CNCPS 7.0, nitrogen flows throughout the cow are better described than previous versions.

A study conducted in our lab capitalized on the power of the new approach, focusing specifically on nitrogen efficiency. Four dietary treatments were formulated, varying in the degree of amino acid balancing and overall nitrogen content in the diets.

Although crude protein ranged from 13.5 percent to 15.5 percent, milk output was not different among treatments, averaging 90 lb/day, and cows fed the 13.5 percent CP diet were more efficient with their available nitrogen compared to their counterparts. What’s more, data from this trial, along with several others, has provided the information to begin calculating optimum amino acid ratios when regressed against the energy content of the diet, much like what is done in swine nutrition.

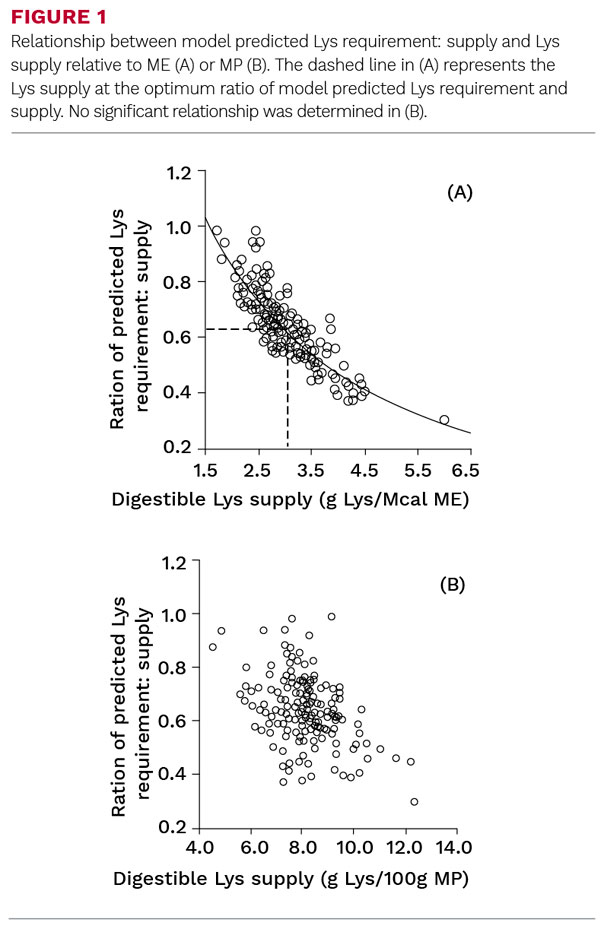

Figure 1A depicts a strong relationship between the ratio of amino acids required to amino acids supplied (AAR:AAS) and the metabolizable energy of the diet. The relationship between AAR:AAS and metabolizable protein (Figure 1B) is not nearly as evident.

When evaluating these figures, you’ll notice the dashed lines that join with the solid, curved trend line. With a little calculus, the point on this trendline where the rate of change away from productive use is found, deeming it the optimum rate at which a given amino acid should be fed at a given energy density of the diet.

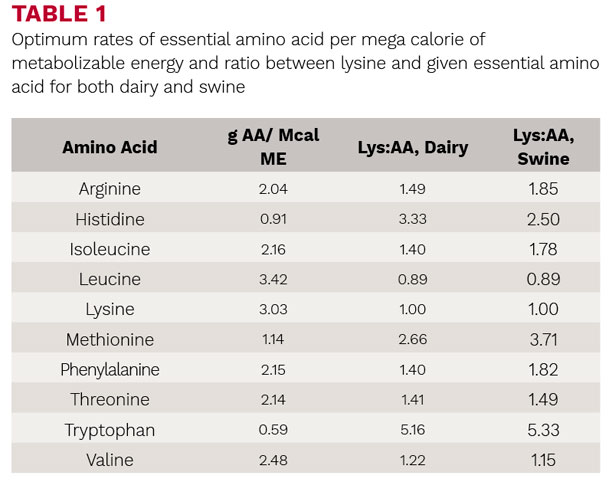

Table 1 lists the optimum rate for all essential amino acids per mega calorie of metabolizable energy.

Following a common practice done in the swine world, if a ratio is created between lysine, typically the most limiting amino acid for swine, and the optimum rate for each essential amino acid, some similarities exist between the cow and the pig.

Following a common practice done in the swine world, if a ratio is created between lysine, typically the most limiting amino acid for swine, and the optimum rate for each essential amino acid, some similarities exist between the cow and the pig.

Efforts to improve these optimum rates of essential amino acids are in the works. Currently, a large pen study is being conducted at the Cornell Ruminant Center, with the hopes of either validating these ratios or improving them.

Three treatment diets, one utilizing the rates seen in Table 1, and two testing the outer boundaries of the variation around each rate, are being formulating using CNCPS 7.0, with the hopes of moving the model closer to commercial rollout.

The results from this study, coupled with data from previous work, could finally allow dairy nutrition to be as precise as the swine industry, particularly when it comes to nitrogen. By doing so, feed expenses can be reduced, nitrogen efficiency is improved, and the Muhammad Ali status is achieved for the bovine athlete.

This article appeared in PRO-DAIRY’s The Manager in July 2018. To learn more about Cornell CALS PRO-DAIRY program, visit PRO-DAIRY Cornell CALS.