As most producers are aware, sick cows behave differently than healthy cows. However, recent research now shows that certain behaviors may also help us identify cows that will become sick in the future. This topic has been a focus of researchers working at the University of British Columbia’s Animal Welfare Program, focused primarily on early behavioral indicators of metritis and lameness.

Metritis (uterine infection) is a costly disease for dairy producers. It has been associated with decreased milk yield, increased risk of culling and decreased reproductive performance. To better understand metritis, a researcher recorded behavior well in advance of calving and then compared the behavior of cows that remained healthy with those diagnosed with metritis a week after calving.

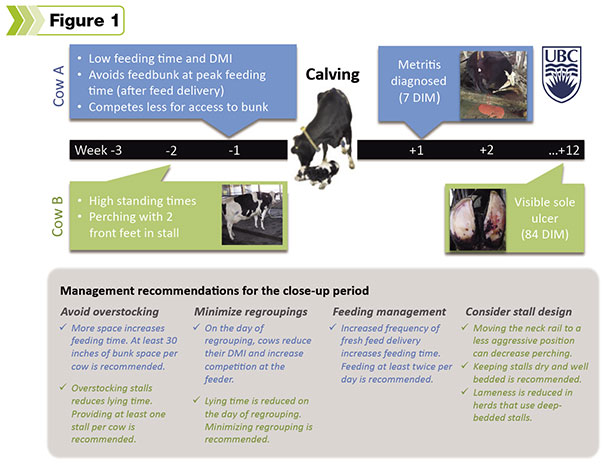

The researcher found that cows with metritis ate less than healthy cows when they were ill, but they actually began eating less up to two weeks before calving and three weeks before diagnosis (Cow A). These cows also avoided the feedbunk during peak feeding times, such as the period immediately after fresh feed delivery, and engaged in fewer competitive interactions at the feedbunk.

Lameness (abnormal gait) is also a major welfare concern for the dairy industry, and it has a clear impact on the profitability of dairy herds. To better understand lameness, a researcher measured the behavior of cows before and after calving, monitoring for sole ulcers and lesions (a main source of lameness) until 12 weeks into lactation.

Cows with ulcers and lesions around eight to 12 weeks after calving spent more time standing during the two weeks before calving compared to healthy cows, which was up to 14 weeks before the ulcer became visible (Cow B). Most interesting was that the high standing time was explained almost entirely by an increase in âperchingâ with their two front feet in the stall.

Behavioral risk factors for lameness and metritis occurred in the close-up period, when proper care and management of cows should be a high priority. To ensure all cows are getting adequate feed intake before calving, producers can decrease competition for feed by allowing at least 30 inches of bunk space per cow.

Producers can also provide fresh feed at least twice a day, as this will ensure that all cows, particularly subordinate cows, will have equal access to the feed. Minimizing the number of times a cow is moved between groups (regrouping) during the dry period can also maximize her feed intake.

To reduce standing time, producers can make every effort to keep clean, well-bedded lying stalls. Deep-bedding is the best recommendation for reducing standing time and lameness, but adding bedding to any surface can help.

It is also important to avoid overstocking at the feedbunk and the lying stalls during the close-up period, as both can impact standing time. To reduce perching time, producers can increase the length of stalls in the close-up period to allow cows to stand with all four feet in the stall.

The length of a stall can easily be changed by moving the neck rail farther away from the curb. We recognize that this will require a concerted effort by producers to maintain stall cleanliness in the dry pen, but it is an option for those who see lameness as a main concern in their herds.

A better understanding of cow behavior can help aid in better management decisions, especially during the calving period when cows are at high risk of disease and lameness. Practical ways of monitoring the behavior of cows are becoming available through technologies such as activity monitors that record standing time.

If lameness or metritis is a problem on your farm, there are management practices you can implement to alter her behavior which may aid in the reduction of these diseases. Clearly, the solutions will need to be tailored to each individual herd, so we encourage producers to consult their nutritionist, herd veterinarian, hoof trimmer and others involved in the day-to-day management of their operation. PD

Katy Proudfoot is an assistant professor with the Department of Veterinary Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Julie Huzzey is a postdoctoral research fellow with the University of British Columbia Animal Welfare Program.