Many farm people have never stopped and actually analyzed why animals behave as they do and, more importantly, what this behavior may mean to their own personal safety. Often animal handling practices are developed from watching others as we grow up on the farm. All too often this results in the perpetuation of poor practices.

Some readers will have heard of a dairy bull or a horse kicking incident where someone lost their life. While most animal injuries are not fatal, many men, women and children involved in agricultural activities will be needlessly injured each year because of a lack of safety awareness of how animals behave. Broken bones, crushed and mashed limbs, missed days of work and unnecessary medical expenses will be the result of injury incidents with animals.

An individual may work carefully around animals a majority of the time, but then involve themselves in an animal incident because of haste, impatience, anger at another person or object or the animal, or because of a preoccupied mind. It is during these moments that a farmer really needs to understand animal behavior.

Animal behavior

Animal behavior can be instinctive or learned. Livestock also learn particular habits and become creatures of those habits. For example, the sound of milking and feeding equipment being started has been observed to cause animals to move toward the milking or feeding area.

Beef, swine and dairy cattle are generally color blind and have poor depth perception, which results in an extreme sensitivity to contrasts. This sensitivity may make an animal balk if a shadow is cast across its path. Due to little depth perception, cattle and swine cannot distinguish blind turns in buildings or alleyways and will move tentatively or not at all, thus frustrating the animal handler. Animals cannot see behind themselves, so will turn to keep the handler or perceived danger in their sight.

Flight zone

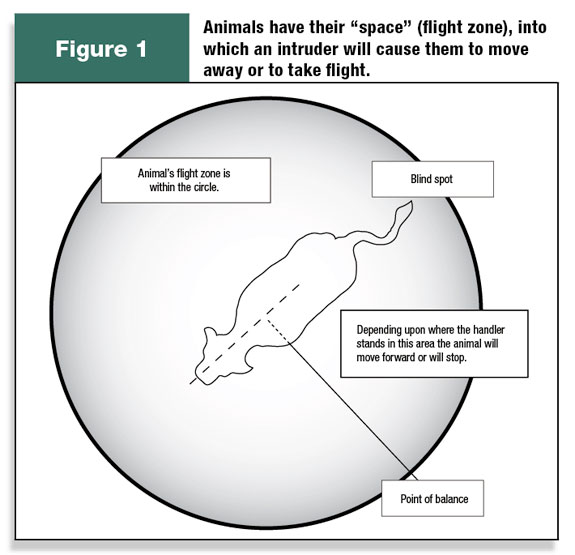

All livestock have a “flight zone.” That flight zone space varies with how tame or wild the animal is. An excited animal has a larger flight zone. When you enter the flight zone the animal turns to move away. If you move outside the flight zone, the animal will turn to look at you. Entering the blind spot of the flight zone unannounced can cause the animal to kick at you.

Most animals have a strong territorial instinct and will develop a sense of “homeland” in their pens, corrals and pastures. They become acclimated to the sights, smells and sounds of that home area and develop a very distinctive and comfortable zone in this area. One example of this homeland trait would be the well-worn paths animals create in most pastures and between pastures and buildings, and water troughs and feedbunks. Animals may even challenge an intruder that comes into that space. Forcible removal from this homeland tends to disturb the animal. Also consider that animals tend to follow a leader when being moved. If no animal makes a move, the group tends not to move from the familiar home area.

Considering these points, it is easy to see why animals often hesitate when going through unfamiliar gates, barn doors, squeeze chutes, etc. Additional shadows cast by lights and yelling by the handler may further compound the problem. Similar problems are created when moving animals away from feed, separating them from the herd or from their young, moving them to unfamiliar areas, or when an unfamiliar human approaches.

Animals are frightened or spooked easily by noise and will always try to move away from the direction or source of the noise. Their eyesight problems may cause them to crash against or through any objects (including humans!) that may be in their path of escape. Animals which are blind or deaf on one side will favor that side and may suddenly swing around to investigate disturbances on their blind or deaf side. If standing too close, you could easily be knocked down and trampled. Move animals with a minimum of noise and confusion.

Moving animals can be made less risky by recognizing the animal’s point of balance (see Figure 1). The animal’s shoulder is its point of balance. To move the animal forward, stand behind the point of balance but out of the blind spot. To stop or slow the animal, step to the front of the point of balance. The need to shout, scream or using prodding devices to move animals will be reduced or eliminated.

The young of most farm animals have the capacity to form relationships simultaneously with their own species and with human handlers. For instance, newborns raised by a bottle or bucket may develop a very strong affection for the person feeding them. Animals do respond to the way they are treated and draw upon past learning experience when reacting to a situation. Thus, animals that are chased, slapped, frightened, etc., in their early life will naturally have a sense of fear when a human is near. Since farm animals do not rate high on lists to receive tender loving care, they are often handled with force unnecessarily.

Animals are often characterized as being “stubborn” because they have balked or refused to enter an area. Once this has happened the animal is likely to refuse the next several times as well and get a little more excited and dangerous with each refusal. It is very important to take time and think out the process of moving the animals before the first attempt. Plan the movement route, observe what areas may have shadows or obstructions, and inform all helpers of what you want to accomplish in moving the animals. Many farmers are tempted to “try it” before thinking and end up in a real battle with the animal, which may lead to an injury.

Injury and fatality considerations

Injuries and fatalities involving animals can generally be grouped into one or more of three categories which reflect the cause of the incident: animal-caused, facility-caused and people-caused. Animals experience hunger, thirst, fear, illness and injury. Females of the species have very strong maternal instincts. Males of the species can be aggressive.

Animals develop individual behavior patterns; i.e., kickers, biters, etc., but all animals are unpredictable in behavior. The handler should be aware of these points and take the necessary precautions to work safely with the animal.

Facilities play a major role in preventing injury and fatality to handlers as well. Keeping walk and work surfaces as clear as possible and properly lighted reduces risk. Pens, chutes, gates, fences and loading ramps should be sturdy, be free of sharp projections and operate properly. Pass-through openings should be provided to allow handlers to get away from animals in an emergency. Good facilities provide a means of controlling animals while allowing easy access for feeding and cleaning, all in a safe environment.

The majority of injury and fatalities due to animals are the result of “people problems.” Lack of judgment or understanding due to inexperience is a major cause of incidents involving animals. Plan ahead to allow plenty of time to move animals so there is no need to hurry. Do not try to manhandle animals when angry. Some handlers may exhibit a feeling of superiority over animals; a foolish act when you consider the size of some farm animals. If the animal becomes nervous and agitated, wait 30 minutes before attempting to work with the animal again.

Conclusion

What can you do to increase your level of safety when handling animals? First, study animal behavior by observing animals in terms described in this article. Secondly, inspect the facilities used to house, control and move animals to be sure that these structures do not cause animals to balk when moved. Finally, recognize that our own actions may be the reason for difficulty in moving or working with animals. By understanding the animal, providing safe facilities, using proper personal protective equipment and working with the animal’s natural instincts, a reduction in injury and fatality incidents involving livestock can be realized. PD

— Excerpts from Penn State University Extension website

-

Dennis Murphy

- Safety Specialist

- Penn State University

- Email Dennis Murphy