In a recent discussion regarding the various proposals for supply management programs in dairy, one participant proclaimed in somewhat of a huff that it would be “unconstitutional” for the government to tell him how much milk he could produce. He went on to argue that no one could penalize him for maintaining or growing his herd. There were some head shakes in agreement, then the head turned towards me. “Is that right?” I was asked. I know I disappointed them when I said it likely would pass constitutional review by the courts. What I did not tell them was why, or even the implications. This is the rest of that answer.

For a long time, almost from the beginning of the Republic, it was generally believed that Congress did not have the authority to regulate businesses located within a state. While our Constitution arose out of a dispute over commerce between two independent states after the Revolution, it spoke only of giving Congress the right to regulate commerce “among the several States,” not within them.

There had been a number of decisions that had begun to erode that sense of protection within the states, but there was still a sense of state empowerment. In an important agriculture case, the Supreme Court clearly held that actions that affected interstate commerce, too, could be regulated by the Congress. The major decision of this point came in a case involving the production of wheat.

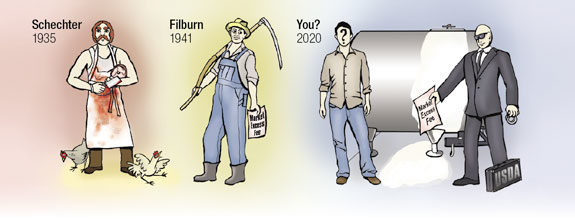

In 1941 Roscoe C. Filburn operated a farm in Montgomery County, Ohio, near Dayton, where he maintained a small herd of dairy cattle and chickens as well as a small acreage of wheat. He sold some of his wheat but consumed some within his farm. How much wheat he did grow resulted in a significant Supreme Court case.

A few years earlier Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. This act authorized narrower powers than the earlier Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which the Supreme Court had held unconstitutional. As summarized by the Supreme Court, the AAA of 1938 was created “to control the volume moving in interstate and foreign commerce in order to avoid surpluses and shortages and the consequent abnormally low or high wheat prices and obstructions to commerce.” (Sound familiar?)

As a result, each year the Secretary of Agriculture could proclaim a national acreage allotment that was ultimately allocated to individual farms and set a penalty on the amount of any excess. The Secretary set a wheat allotment for Filburn of 11.1 acres with a yield of 20.1 bushels. He planted 23 acres and the excess acres yielded 239 bushels of “marketing excess.” He was penalized 49 cents per bushel, or one-half of the parity price.

Filburn challenged the penalty. He claimed, among other things, that the excess of the wheat would be used only on his farm as feed to his animals and that Congress could not regulate his production of wheat for his farm. The Supreme Court held that under the Commerce Clause, Congress could call for the implementations of quotas and penalties, even if the product was not technically marketed so long as it affected commerce.

With what he grew and used on his farm, he would not be buying that wheat. As a result, his production and farm use reduced demand for wheat grown elsewhere. In short, he was affecting interstate commerce of wheat, and Congress could regulate it. This decision (Wichard v. Filburn, 217 U.S. 111) provides the legal basis for those who seek to establish a similar program for milk production. (You can get a copy of the Supreme Court’s decision online, found at www.findlaw.com/casecode/supreme.html, in the “citation search” tab, enter 217 and 111.)

Here the penalty was relatively minor, while the principle of law was huge. Sometimes the penalty and the decision are both significant. In 1935 Aaron Schechter was in deep trouble. Along with his brothers, Martin and Alex, and his father, Joseph, and the two companies they owned, they had just been convicted of 19 counts of criminal conduct against the U.S.

The penalty was $8,500 in fines. For 1935, after the second market crash and in the midst of a full blown depression, that was an enormous amount of money. The average annual wage was only $1,600 and bread was 8 cents a loaf. By today’s standards, the amount was about $135,000.

Two years earlier, Congress, at the urging of President Franklin Roosevelt, had passed the National Industrial Recovery Act. This law authorized the creation and empowerment of the National Recovery Administration (NRA) under the control of the president to regulate every industry from Washington down to such details as to how much to charge and how to choose chickens for sale. A tandem act, the Agriculture Adjustment Act, created the Agriculture Adjustment Administration, which had similar powers, but over agriculture including milk.

Prior to the passage of those bills, such regulations, if they existed at all, were done at the local or state level. These bills constituted a wholesale transfer of power from the local and state governments to the federal government.

Under the powers granted, the president created the “Code of Fair Competition for the Live Poultry Industry of the Metropolitan Area in and about the City of New York,” better known as the “Live Poultry Code.” Violations of the code were criminal and subjected the individuals to $500 fines per offense. Similar codes were instituted for milk and milk sales in regions around the country.

The Schechters operated a business in Brooklyn and had come under suspicion by the U.S. government for violating a new code issued by the president. These were not money tycoons, but poultry butchers. (Their name “Schechter” means “butcher.”) Among the 19 counts were several regarding the selling of unhealthy birds, thus the origin of the case’s nickname – “The Sick Chicken Case.”

Most of the charges for which they were ultimately convicted (they were originally charged with 60) were for violating the Poultry Code’s requirement of “straight killing.” As the Supreme Court noted, this was really a requirement of “straight” selling. It required those who purchased poultry for resale to accept the run of the coop.

That is, you took the whole coop, or half coop, and could not choose individual birds or sort them for quality. The Schechters were charged criminally for permitting their retail dealers and butchers the choice of individual birds rather than forcing them to take the whole coop.

After conviction, the defendants appealed to the Court of Appeals, which dismissed several of the charges. The Supreme Court accepted the case for review. There the court, in one of its most momentous decisions, declared the NRA to be unconstitutional and an exercise of power outside the authority of the Congress. (A copy of this decision is available as noted before, but by entering the codes 295 and 495 in the citation search.)

Shortly after this, the court held the AAA unconstitutional. That law authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to issue licenses to handlers of commodities and regulate production through regulations on these licenses. It also allowed the Secretary of Agriculture to impose taxes to effectively control production.

Among the commodities affected was cotton. This decision together with U.S. v. Butler (297 U.S. 1), decided a year later, held the AAA unconstitutional and brought an end to the wholesale transfer of power. Roosevelt and his administration were stopped in their revolution to change the nature of the American economy and replace it with a government- controlled economy.

In retrospect, it seems a lot of what they wanted then has evolved to be the case today. An excellent book, one I recommend to anyone who has an interest in the history of that era, and one eerily reflective of today’s political environment, is The Forgotten Man by Amity Shaes. The book chronicles the Schechters’ case, among other stories, in the context of the massive change in government that occurred from the 1920s to 1940.

The Schechter Poultry and Filburn cases are important cases of the argument now being used in challenges to the recently passed health care legislation: Exactly how far does Congressional power reach in the everyday lives of Americans? The question of federal power over the production of wheat growers, butchers or dairy farmers takes on a personal meaning when a step out of bounds can mean criminal charges or crippling fines.

This discussion of enforcement, and its impact, of any scheme for supply management, has largely been ignored, or even denied in the discussion. Regardless which one of the various proposals might be adopted, they all will require the government to enforce the penalties and the quotas.

Despite claims to the contrary, it has to be that way. Whether it is an administrator or a committee of farmers, ultimately it is a government official who will use the full force of the U.S. Department of Justice and the courts to enforce the controls.

These supply management programs are all about managing growth. If they were not, why even pass them? The goal is to have less milk at times in order to maintain a higher milk price. To have less milk, producers cannot grow – they have to stay even or shrink from what they were or would have been. Once a target or quota or base is set, then any production in excess subjects the producer to a penalty. Some proposed penalties are higher than others. Those, themselves can be a problem.

More importantly, however, such a new policy restricting growth to set levels makes a national policy that says that dairy farms that fully seek to be efficient, innovative and productive, can potentially be in violation of federal policy. Violating an express government policy can subject producers or others separately to even more serious crimes, with not only the risk of fines but also imprisonment or forfeiture of the farm itself.

In his book, Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent, Harvey Silvergate explains how overly broad federal conspiracy and fraud statutes permit federal prosecutors to use policies in statutes to turn innocent business behavior into criminal acts, even if such is not detailed within the law used as a basis for the crime.

The Schechters, though saved by the Supreme Court, understood what happens when the government looked into their business. Filburn certainly understood as well. It is not a question of whether we should adopt or not this or that supply management program.

Rather, before we invite the government further into our barns and our lives, let’s make sure that the real benefits of those programs outweigh the exposure to an overzealous government enforcement. PD

-

Ben Yale

- Attorney

- Yale Law Offices

- Email Ben Yale