In 2014, when producer milk was priced at over $24 per hundredweight (cwt), making money was pretty easy. In 2008, when prices fell to $12 per cwt, it’s doubtful any producer was making money. More recently, prices have hovered in the $15-to-$17-per-cwt range. Some have made money, but a lot of others have struggled.

This article will discuss:

- Why the price has been so volatile and how that might be changing in the future.

- Why component production is so important now and will be even more so in the future.

- How a producer can increase profitability and cash flow in this changing environment.

Current price volatility

First, what makes producer prices so volatile? Dairying is probably one of the most difficult businesses to manage while consistently making money. Historically, overproduction has been the main culprit for volatility.

There has been a pattern of high prices and expansion followed by exits from the dairy business and reduced production, leading to a return to higher prices. This pattern followed a fairly consistent three-year cycle when the U.S. market was isolated from the global dairy environment.

Future price volatility

The U.S. dairy industry has become more involved in international markets. Products like nonfat dry milk/skim milk powder (NDM/SMP), dry whey and lactose are now heavily dependent on global markets, with one-half or more of U.S. production now exported.

Exports are dependent on exchange rates, international events and countries’ import barriers. Some of these products are also imported when global competitors are selling below U.S. prices. Being part of the international dairy markets obviously creates an environment for significantly increased U.S. price volatility.

Moving forward, the U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) is strengthening exporting efforts, with increased activity focused on cheese. Currently, about 6 percent of U.S. cheese production is exported.

Because cheese price is the most important element in calculation of Class III milk prices, cheese exports are key to producer milk prices. But as cheese exports grow, more price volatility can be expected.

Component demand

Why is component production so important? The simple answer is that the majority of U.S. producers are paid based on milk components. There is no payment for the water in milk. However, the importance of components goes further. Trends in dairy product consumption are changing. Key long-term trends, established over decades, will no doubt continue.

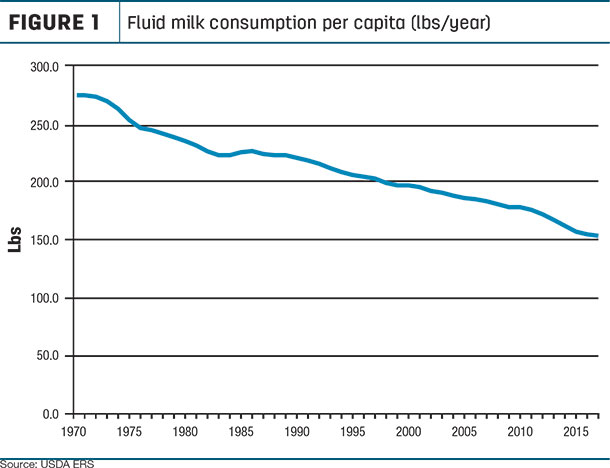

Fluid milk consumption has been decreasing, and will continue to decrease (Figure 1).

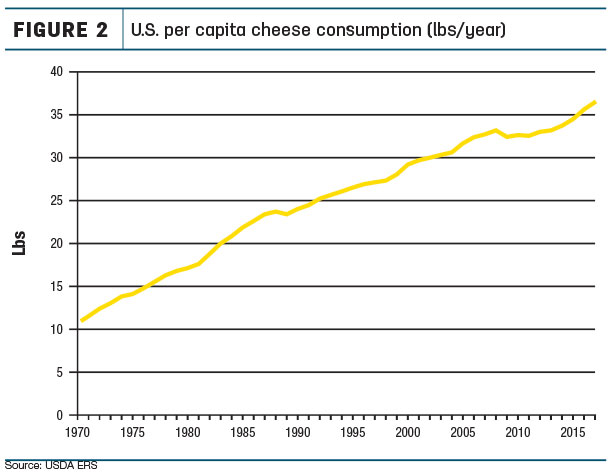

Cheese consumption has increased and will continue to grow (Figure 2). While NDM/SMP is the largest export item, export volumes of whole milk powder (WMP) are also increasing. Milk component production is and will continue to be economically important.

Impact of price changes

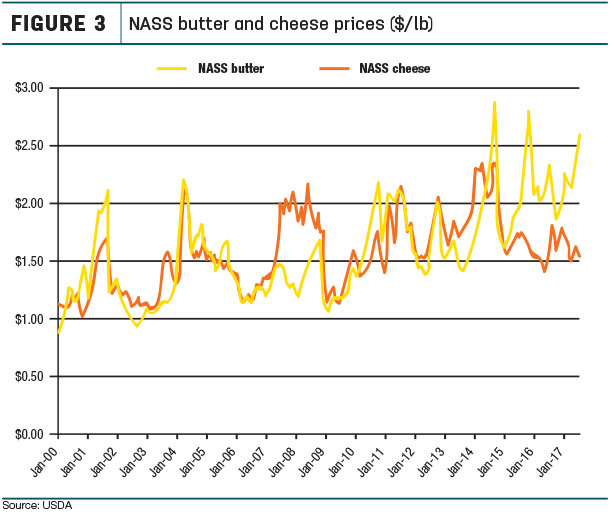

Prices of cheese and butter are used to calculate producer milk protein and butterfat prices. Figure 3 shows average annual cheese and butter prices since 2000. Cheese and butter prices typically move up and down together.

When there are large differences in cheese and butter prices, they are typically less than 70 cents per pound. (Periods when differences are greater than 70 cents per pound are treated as “outliers” in the analytical tables discussed below.)

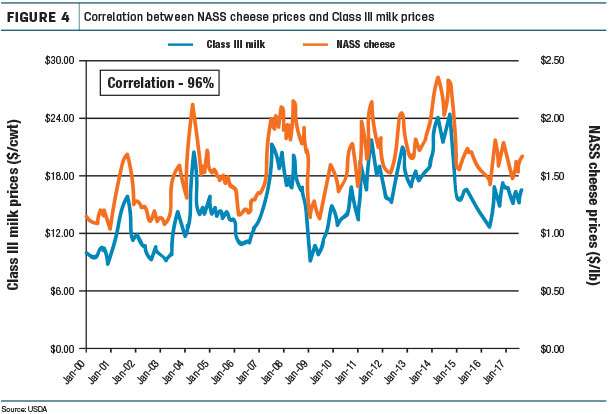

When the cheese and butter prices change, the Class III price changes. However, when only cheese prices change, the Class III price changes a lot. When only butter prices change, there is a smaller change in the Class III price. As shown in Figure 4, there is a 96 percent correlation between the price of cheese and the Class III price.

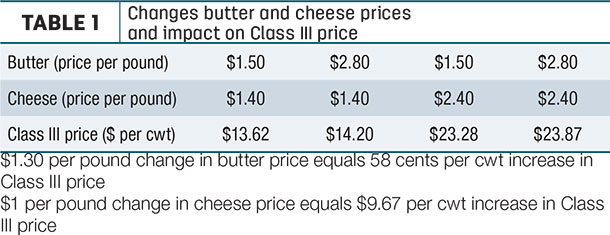

Table 1 illustrates how changes in cheese and butter prices impact the Class III milk price.

A $1-per-pound change in the cheese price (from $1.40 to $2.40 per pound) changes the Class III milk price by $9.67 per cwt. In contrast, a $1.30-per-pound change in the butter price (from $1.50 to $2.80 per pound) changes the Class III price by only 58 cents per cwt.

What can the producer control?

A dairy producer has no control over Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) prices. However, through genetics, feeding and management, producers have some control over the level of milk components their cows produce.

The analysis below discusses how a focus on increased milk component levels – in this case achieved through herd nutrition changes – can impact milk prices.

It summarizes component changes in feeding trials involving thousands of cows in many diverse geographic locations, compiled by Dr. Brian Sloan, global ruminant business director for Adisseo. By fine-tuning nutrition, milk components increased by an average of 0.14 percent for milk protein and 0.16 percent for butterfat.

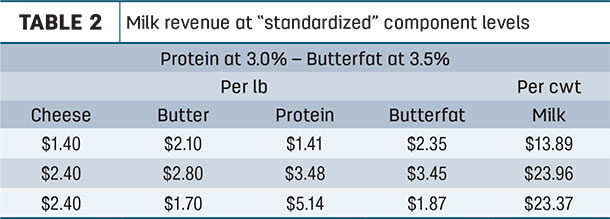

To establish a starting point for measurement of the economic impact of these changes, the standardized levels (3 percent protein and 3.5 percent butterfat) used for FMMO milk classifications were used.

Table 2 shows the calculated Class III price at various prices of cheese and butter. All of these prices variations have actually occurred over the last four years.

The first row of data in Table 2 shows the value of protein and butterfat when cheese is at a low of $1.40 per pound and butter is $2.10 per pound. At those prices, Class III milk is valued at $13.89 per cwt.

The second row uses cheese and butter at much higher prices. With cheese at $2.40 per pound and butter at $2.80 per pound, the price of Class III milk skyrockets to $23.96 per cwt.

Row three of the data is based on a higher price for cheese ($2.40 per pound) and a lower price for butter ($1.70 per pound).

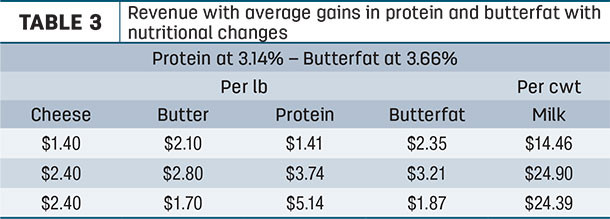

Table 3 shows the value of Class III milk with the average gain in components summarized in the feeding trials referenced above. Protein levels are now at 3.14 percent and butterfat levels are at 3.66 percent.

At these levels, the value of milk has increased by 57 cents per cwt (Table 3 compared to Table 2) at low cheese prices and $1 per cwt at higher cheese prices.

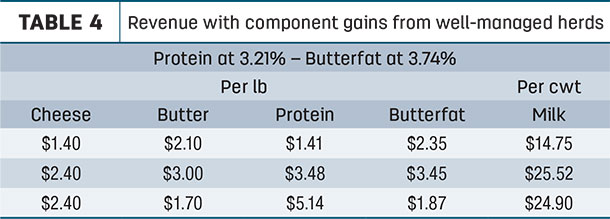

Table 4 makes the same calculations, but for herds making the highest gains in component production (3.21 percent protein and 3.74 percent butterfat) in the field trials.

In this case, the value of milk increased 86 cents per cwt (Table 4 compared to Table 2) at lower butter and cheese prices, and $1.50 per cwt at higher cheese prices.

In this case, the value of milk increased 86 cents per cwt (Table 4 compared to Table 2) at lower butter and cheese prices, and $1.50 per cwt at higher cheese prices.

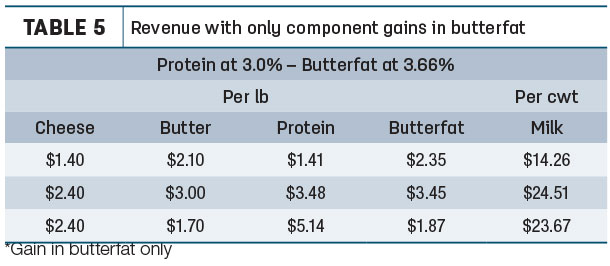

Table 5 shows the gains if minor nutritional changes are made in an attempt to increase just butterfat.

In all cases, the increase in the Class III price in Table 5 is less than in Tables 3 and 4 where the standard nutritional changes were made.

The practice of chasing the market price for cheese and butter by continuously changing nutrition is a risky practice. Properly designed diets to meet nutritional needs supporting component production – and sticking with those diets regardless of short-term market fluctuations – provide the highest returns.

Based on this analysis, optimizing dairy rations to meet the nutritional, health and production needs of the cow, while focusing on milk components, will provide a positive and continuing increase in cash flow, according to Sloan.

Chuck Schwab, Ph.D., principal, Schwab Consulting, and professor emeritus of animal sciences at the University of New Hampshire, agrees. “Dairy nutritionists who became aggressive years ago in formulating for key nutrients to maximize milk components have never looked back, regardless of milk prices,” says Schwab.

It’s estimated approximately 20 to 30 percent of U.S. dairy cows are fed diets to boost production of components. What is somewhat amazing is that 70 to 80 percent of cows are not fed these diets, which could very positively impact a producer’s finances. Producers should work with their nutritionist, review feed formulations and make cost-effective adjustments.

“We have entered a new era in the dairy industry. We are looking at a time when pounds of solids will be more important than ever due to production limitations set by processors and the ever-increasing need for more butter and cheese in the American diet,” says Jessica Tekippe, ruminant product manager for Ajinomoto Heartland.

“This makes it vital for producers to re-evaluate their feeding strategies to ensure they are capitalizing on all the proven technologies they have available to help them reach higher component levels.” ![]()

-

John Geuss

- John Geuss Consulting

- Email John Geuss