Dairy farmers thinking about investing in automated milking technology can position themselves for the best chances of loan approval by understanding what it is their lenders need from them.

“I think the future is in milking robots,” Bruce Dehm, agriculture economist with Dehm Associates LLC, a Farm Business Services company, told dairy farmers at the 2018 DeLaval Robotics World Series held June 27-28 in Madison, Wisconsin. He added, “The economics right now are about the same [as a parlor], but I think that is going to change as labor gets more expensive.”

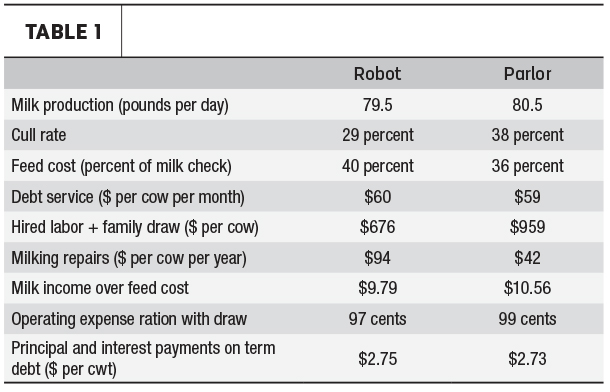

According to his data analysis of 14 robotic and 43 traditional parlor herds located in the Northeast, Dehm said, “The cost of production is about the same” for both cow-milking methods. His analysis included the following benchmarks in Table 1.

When planning for the future, one major variable cost of parlors cannot be avoided: hired labor. Dehm works with many dairies in the state of New York, where the minimum wage is on an upward tick to reach $12.50 per hour by 2021. He said that equates into a $200 increase in cost per cow for labor on dairies with parlors. How can dairy farmers make up for this? The answer: possibly by “eliminating some of our labor and making it a fixed cost.”

Paying upfront for labor with a robot means a larger capital investment than a milking parlor, which can be a risk that leaves some lenders uncertain. Dehm offered his advice for dairy farmers on educating their lenders and helping them understand how automated milking can be a part of a long-term plan for a successful dairy operation.

“Work hard to put a business plan together so you get the ‘yes’ instead of a ‘no’ from your lender that doesn’t quite understand the new technology,” he said. A good plan should include the following:

1. Security and collateral. The lender wants to know that there is enough equity in the operation, whether it’s in real estate, barns, livestock or equipment, to ensure they are covered if things “go south,” Dehm said. Often, an FSA guarantee is part of that structure.

2. Cash flow. Lenders want to know the producer is positioned to make money with a robotic investment and will be able to pay back the loans. “You don’t want to go to the banker and have them come up with the number,” Dehm said. “You want to come up with the number and go to them and say, ‘Yes, we can make it cash flow.’”

3. Confidence in the ability to run the business. The lender finds value in working with customers who know their business and how to run it. With this confidence, they can take a financing proposal to their loan committees and advocate for approval. That is why it’s important to provide thorough, detailed information to the lender.

Dehm suggested becoming familiar with these documents: balance sheets, income statements and cash flows.

Balance sheet: One purpose of this document is for the lender to make sure there is enough collateral, but the major purpose of the balance sheet is to have one at the beginning and one at the end of a period (i.e., year) to create an accurate accrual-based income statement.

Income statement: “Putting together an accrual income statement every year will help you understand your business, and it will help your lender understand your business,” Dehm said. This goes beyond a Schedule F to more accurately reflect the operation’s position.

“Oftentimes, cash accounting systems match up to the Schedule F, but if you really want to find out why costs are higher than other farms, you need to institute a managerial chart of accounts on your farm,” Dehm said. “You may have one line item for breeding that you keep all your expenses on, but if you want to start controlling some costs on your farm, you need to know what is in those costs.” For example, breeding may be broken out to include semen costs, arm service, embryo costs, hormones and so on.

Cash-flow projections: Get a handle on cash inflow and outflow by going through each expense, and anticipate changes based on what will happen with costs relative to the proposed changes (i.e., bedding, milkhouse supplies, etc.). Figure out the breakeven milk production and milk price.

Before meeting with the lender, sit down and really figure out what is needed for funds. If necessary, enlist the help of an extension agent or someone who specializes in this type of planning. Be ready to present to the lender the projected term note and mortgage payment. “This is something you want to bring to them, and not have them tell you what it’s going to be,” Dehm said.

Also, determine the debt per cow in the proposed facility. “In a lot of plans I put together, debt per cow with robots is in the $7,000 range, and that really scares lenders, but they don’t understand the cash-flow implications of not having the labor.”

Dehm recommends taking it a step further by evaluating debt on a hundredweight basis, monthly debt service, interest rates overall, average term and when the debt will be paid off. Look at numbers like farm debt service as a percentage of the milk check.

“If you’re in the 20 percent range, you are golden, more than likely,” he said. “If you’re 25 percent or higher, you are probably going to have a hard time because you won’t have enough money left over to pay for everything else, generally speaking.”

The planning for a transition to robotic dairying includes tremendous detail and an in-depth look at the dairy’s finances and business plan.

“It’s important to first do this before making any big decisions,” Dehm advised. “Do we have enough equity to take on this many robots? If not, then come up with a plan.”

Doing this will demonstrate to the lender a commitment to running a successful business before and after robots are installed. ![]()

-

Peggy Coffeen

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Peggy Coffeen