A hallmark of 2020 was the degree of unpredictability. How many times in the last 12 months have we felt like saying, “I didn’t see that coming.” As we look forward to having that annus horribilis behind us, it is time to consider what we might expect in the year ahead.

I’m hoping that we have hundreds of millions of sore arms in our future as the population receives its vaccinations for COVID-19. We really can’t put major disruptions to supply chains in the history books until the pandemic is beaten back.

Even responses to help, like Farmers to Families Food Boxes, have been disruptive. Although they have filled a great need to supply food to hungry people, they have also caused large pulses of demand for specific products, like fresh cheese, that have left markets scrambling to fill the pipeline.

Slower, steadier demand that can be well anticipated keeps markets on course. I’ve spoken with many folks in plants or retail chains who have said that our long-term demand planning used to be annual, with quarterly updates. In the midst of the pandemic, long-term planning became a matter of weeks.

For instance, as restaurants try to reopen, they have restocked their kitchens week by week, not knowing if they would be closed again a few weeks later. That short-term demand worked its way back down the pipeline to plants who were expected to have product inventory ready to fill unknown orders. And that pushes back to farms to keep milk in the pipeline and back to cows that didn’t get the memo about turning production on and off.

How bad was farm income?

We all remember last April’s headlines about farm milk being dumped. That is what happens at the extreme when we simply don’t have plant capacity or customers for the product that would be made from the extra milk. I’m getting a bit concerned about those headlines again this year.

Milk income in 2020 was much better than anticipated. Last May, the U.S. all-milk price hit a low of $13.60 per hundredweight (cwt), a low not seen since 2009. By November, the price was $21.30 per cwt, a high we hadn’t experienced since 2014. The annual average price will be about $18.24 per cwt, which wasn’t quite as high as the 2019 average, but still a strong showing compared to prices since 2015.

On top of the all-milk price, we had other milk-related income. For those who signed up for the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program at the $9.50 level, the net benefit (indemnities minus premiums) averaged about 67 cents per cwt on all Tier I milk for the year. Also, about 30% of U.S. milk was covered under the Dairy Revenue Protection (Dairy-RP) program, which paid out about $400 million.

Let’s not forget the two rounds of direct payments to producers under the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). Those averaged about $2.45 per cwt for all milk production in 2020. Taken together, the net milk income from the market and various programs was by far the best income year that we have seen since 2014.

This much better income has helped to stabilize the loss of dairy farms that we saw in 2019. It has also added cows to the national herd since July and stimulated additional milk production per cow. Collectively, we are increasing milk production at a high rate and you have to wonder if we can handle the surge.

Plant capacity to the rescue?

Perhaps we won’t have as much milk dumping as new cheese-plant capacity comes online. A large new plant in central Michigan will take much of the pressure off that state’s production. There are also a couple of significant expansions in the I-29 corridor and another in Wisconsin. This may help us get milk processed, but will we have customers for the extra cheese?

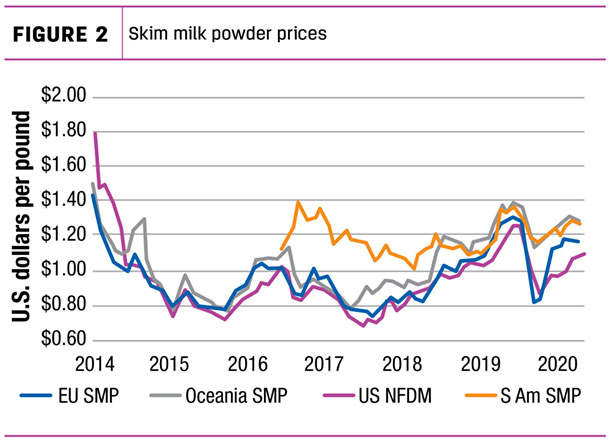

If the price is right, we can find customers. Last April, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) spot price for cheese touched $1 per pound, a price we hadn’t seen since 2006. This was well less than export competitors, like New Zealand, whose price was about $1.80 per pound, at that time. Given those prices, we had a little burst of export cheese sales. But six weeks later, CME spot prices had spiked to $3 per pound, which was the highest price we had ever seen. Opportunistic export sales stopped.

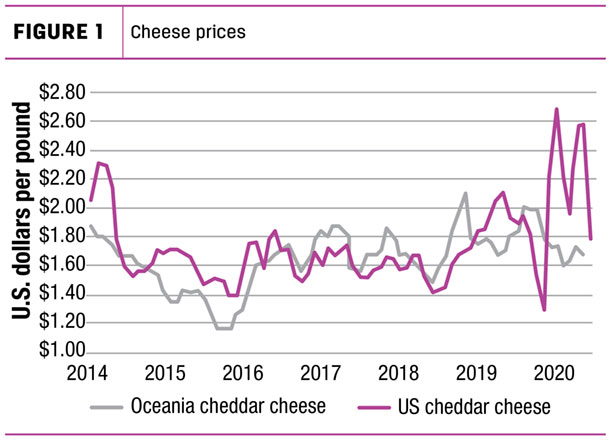

Our skim milk powder prices have been competitive for years and are often the price leader in export markets. This provides our dairy industry with a steadier but lower Class IV milk price when compared with Class III prices, which usually float on domestic demand.

The new cheese capacity may put enough new product on the cheddar market that cheese prices begin to clear with exports, much like powder prices. That should give us less price volatility but at a somewhat lower level.

The extra cheese capacity may also help with what has become an annoying problem for producers: negative producer price differentials (PPDs). One of the drivers causing this on milk checks is the divergence between Class III and Class IV prices. When we pay more out in Class III component values than has been collected in the Federal Milk Marketing Order pool, the PPD is negative. Having Class III and Class IV prices converge would make that a less-likely proposition.

Export opportunities

I think it is likely that 2021 will show us more export opportunities for cheese. In the last couple of years, countries like South Korea, Japan and others in Southeast Asia have increased their purchases from the U.S. But our major customer for cheese exports has been Mexico, and there is a more troubling trend there.

U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum caused Mexico to retaliate with tariffs on U.S.-sourced cheese. It also had the effect of Mexico exploring other sources for dairy products. Although we have largely restored that relationship, Mexico has kept a more diversified sourcing for products.

Perhaps the larger issue for Mexico is the country’s economy. Even before the pandemic, they were struggling, and the value of the peso has been in decline relative to the U.S. dollar. That makes U.S. cheese look more expensive to Mexico’s consumers.

The bottom line

Price forecasting in a pandemic is a fool’s errand. That said, I think we’ll get the coronavirus under control in 2021 and begin the work of restoring the economy. Battling back to full employment will take a few years, and there will be some hard decisions about national spending as we whittle back the deficit.

I believe our domestic consumption of dairy products will get back on track and that new export opportunities may dampen some of the wild price swings of the past year. Let’s look forward to what the new year brings.