As we continue to move through the uncharted territory of COVID-19, lower-than-expected mailbox price is yet another shock dairy farmers face, even as other parts of the dairy industry recover. To better understand mailbox prices and how they differ from futures prices, let’s dig into dairy’s complex pricing mechanisms: federal milk marketing orders (FMMOs), producer price differentials (PPDs) and pooling, and cooperative pricing.

Federal milk marketing orders

Like much of America’s farm policy, FMMOs date back to the Great Depression of the 1930s. FMMOs were originally designed to help even out the Dust Bowl era’s wildly divergent milk prices and essentially create a price floor for fresh milk producers. Over the last 90 years, pricing formulas, marketing areas, milk classification systems and more have changed in the FMMOs, with the most recent changes to FMMO Class I pricing going into effect in 2019. Currently, there are 11 FMMOs representing about three-quarters of all milk produced in the U.S. The Upper Midwest Federal Order 30 covers the geographic area of Minnesota, Wisconsin and part of the Dakotas.

Pooling

Producer price differentials (PPDs) and pooling helps ensure consistent formula-based mailbox price for producers in the same marketing area, regardless of whether their milk ultimately goes to fluid milk (Class I), soft products like ice cream and yogurt (Class II), hard cheese and whey (Class III) or butter and milk products (Class IV). Typically, Class I fluid milk has the highest market value of all milk classifications within a marketing area, followed in descending order by Class II, Class III and Class IV. But, milk pricing does weird things sometimes. Under the Upper Midwest Federal Order 30 (our marketing order in Minnesota), about four-fifths of production goes to Class III products like cheese. Due to the strong processing demand for cheese in our region, Class III has been priced above Class I about a dozen times since 2000. June 2020 is one of those price inversions, with Class III dramatically higher than Class I in the Upper Midwest. After several months of low demand due to the repercussions of COVID-19, cheese prices are on fire again.

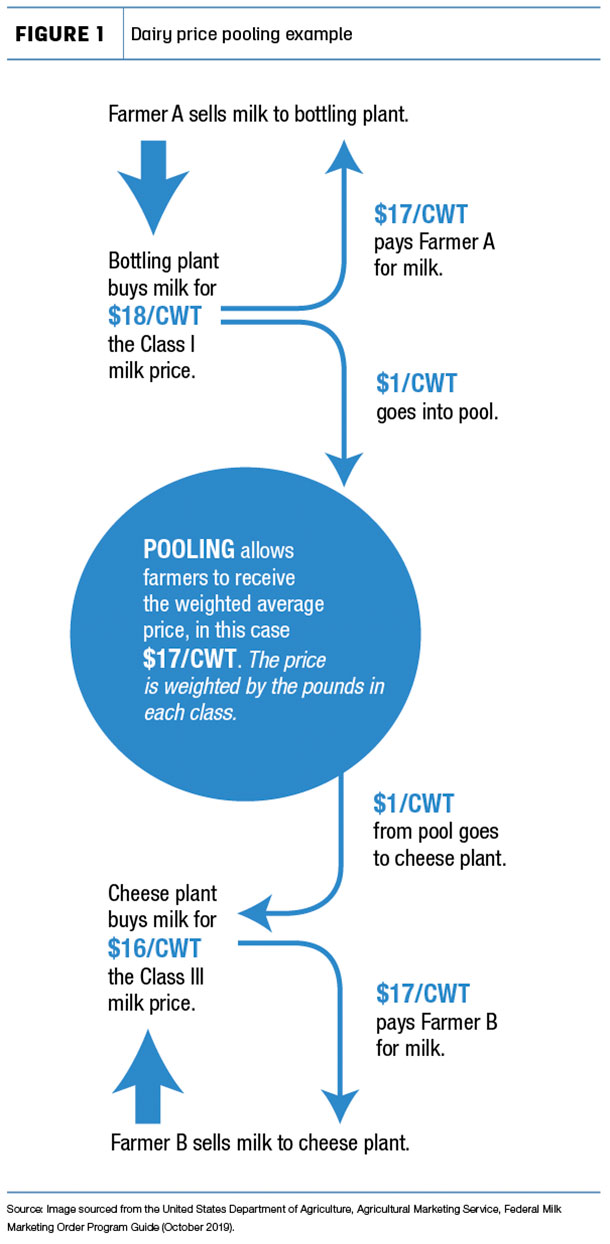

FMMO 30 uses the components from Class III to form the basis for price pooling. Class I and II prices are announced ahead of time to processors, and Class III and Class IV are derived after the fact based on actual components prices. Any difference between class pricing is the PPD, and producers receive a weighted average price. When class pricing is working like it should, there is money left over in the pool from higher Class I prices to even out lower Class III prices (see Figure 1). This summer, the pre-announced Class I prices have been substantially lower than the actual derived component prices for the other classes. With a price inversion of Class III prices higher than Class I, the pool is “short” money, and mailbox prices become a guessing game for dairy farmers.

As long as they abide by the guidelines of their FMMO, processing plants that do not make Class I fluid milk do not have to participate in pooling. This adds another wrinkle: Cheese plants can depool under FMMO 30. Right now, this would help prices for dairy farmers that sell to those processing plants.

More price considerations

If a creamery is a cooperative, there are additional mathematical formulas involved in determining prices. During the March and April 2020 lows, a cooperative may have cushioned mailbox price above the weighted pool average. Now that market prices have risen, they may need to even out payments. Or, if a cooperative had to resell milk below market price during stay-at-home orders, it may have spread that loss across members by using deductions, lowering mailbox price. If a cooperative uses base/excess pricing plans, pricing for excess production has been particularly hard hit.

One additional note for dairy farmers to think about when they look at their milk check is that we’ve had some very hot, very humid weather this summer. Outside of all the COVID-19 price issues, component payments may be down, as cows react to sweltering summer days by producing less butterfat and protein.

Understanding dairy’s complex pricing under FMMOs can help bring you some clarity as you look at 2020’s summer milk checks, which have brought both very low and, in some cases, very high revenues. Furthermore, if you’re using dairy risk management strategies, such as futures and options, margin coverage or other programs, it is helpful to remember that your mailbox base price may not correspond with the prices used for risk management strategies. Being aware of pricing mechanism differences can help you manage risk in way that best fits the needs of your dairy farm as we continue to traverse 2020 markets. ![]()

This originally appeared in University of Minnesota Extension newsletter. For more ag business management content, visit the UMN blog. If you need more information about farm financial programs from the USDA, the Small Business Administration or the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, check out the University of Minnesota Extension’s online guide or call the extension’s farm information line at 1-800-232-9077.

Megan L Roberts is an extension educator in agricultural business management at UMN. Email Megan Roberts.