If you make your way through any of your local stores, likely you have found yourself asking the question, “Why does this cost so much?” Perhaps you have seen the illustration that so vividly breaks down a box of corn flakes according to its components and their contribution to the price of that cereal.

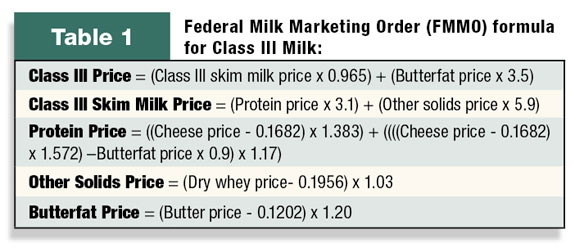

If you were wondering, there is roughly only $0.06 of corn in an 18-ounce box. When it comes to pricing milk at the farm gate, the process of arriving at the monthly announced price is just as jaw-dropping. Since there is not enough room in this article to verbally articulate the process, I thought I would just give you the formula. Let’s begin with Class III milk. Here goes…

See Table 1 .

I know that is a lot to look at and even more to digest. Admittedly, we use a spreadsheet to track this. This is not where it ends, though. When it comes to the federal order system, there is more than just a Class III price. In fact, milk is classified into four different classes by the end use of the product. Class I milk includes bottled fluid milk, cultured buttermilk and eggnog. Class II milk is manufactured into ice cream, yogurt, cottage cheese and packaged cream. Class III milk is made into cheese and cream cheese. Class IV milk is processed into butter and non-fat dry milk.

Today, about 65 percent of all Grade A milk is priced in the 10 federal milk marketing orders. These “orders” are nothing more than a set of regions throughout the country as drawn out by the USDA. For example, Texas, New Mexico and a part of southwest Colorado make up the Southwest Order, while Wisconsin and Minnesota along with parts of Illinois, Iowa, North Dakota and South Dakota make up the Upper Midwest Order. Florida and Arizona each have their own orders. The lion’s share of what is not priced through a federal order is priced by California’s state milk marketing order.

Each month, the USDA announces a set of minimum prices for each class of milk within the FMMO by using product price formulas (like the one seen above). These formulas take the dairy product price minus the make allowance (the cost of manufacturing) times the yield of the product. As we examine the formula for Class III price, we can see that it is based on cheddar cheese, butter and dry whey prices. The Class IV price is based on non-fat dry milk and butter prices. The Class II price joins the price of butterfat (the same one used for Class III and IV pricing) with the advanced Class IV price (determined prior to the month of product manufacture) with an added $0.70 for skim milk.

The Class I price gets a bit more difficult. Its formula reflects an advanced Class III or Class IV price plus a Class I differential (a factor that varies from county to county and takes into consideration the distance to the nearest bottling plant). Some will argue the efficacy of the process, the validity of the formulas, the method of data collection, the specific products used or otherwise. However, the simple fact is that whether you are talking Class I, II, III or IV, pricing of the raw milk at the farm is determined by the wholesale pricing of the product before it makes its way to the store shelves.

If we are to have any sort of discussion, then, about the price of milk, we cannot isolate it from a discussion of the product. Product pricing and the supply and demand features that drive it are a leading force in our discussion about 2010 milk pricing. We have talked about the three-year milk cycle in this periodical in previous writings. Running from low price to low price, the cycle suggested that 2009 would be a poor year. However, there is no way of knowing how high the market will rebound following those low prices. That remains largely in the hands of herd size, milk production, the domestic and global economy and the broader need and outlook for, you guessed it…product pricing.

As you read this article, we will be reaching peak production in the U.S., a period we often refer to as the “spring flush.” Milk volumes are generally abundant and processors waste no time in converting it to product. We generally build inventories this time of year and consequently burden the farm price for milk. That does not always mean that prices go lower. It sometimes means that we just don’t go as high as we would otherwise. In other instances, times of big consumer demand can push through these inventory hurdles to create rather nice pricing opportunities.

It is the hope of many a dairyman that this type of condition is born again in the dairy marketplace. However, at the time of this writing, current product prices ($1.26 cheese, $0.32 whey and $1.45 butter) suggest prices stay below $13 a hundredweight while current Class III futures are averaging just under $15 for the last half of the year.

Could prices move even lower? Is my waiting for better prices warranted? …Or should I begin addressing the price of milk now? The answers to these questions are as numerous as the people that ask them. Some dairymen capitalized on the high price offerings of 2008 and dodged the bullet that was shot in 2009. Their equity position is still strong and they are riding the wave of the three-year cycle that has become so prominent in the dairy industry. Many dairymen, however, were not protected from the substantial price fall that raped and pillaged the equity found in American dairies. This presents a problem. Many of these dairymen recognize a need to protect themselves from the ugliness of 2009, but lack the cash to aggressively address price. Marketing then becomes a matter of priority.

How does it rank in your operation? To answer that question, many will want to know where the price of milk will be. The real question is “Where will product prices be this summer/fall/winter?” No one, of course, knows the answer to that question. What you must ask yourself is “How much is that $2 per hundredweight worth to me?” As I warned in my last article, you don’t want to act rashly. I suggest talking with your market adviser about a put option strategy that affords you the “right to be wrong.” Give yourself the luxury of having downside coverage coupled with available upside opportunity. $15 per hundredweight is a price worth addressing. We know what goes into it. What will you get out of it? PD

PHOTO: The simple fact is that whether you are talking Class I, II, III or IV, pricing of raw milk at the farm is determined by the wholesale pricing of the product before it makes its way to the store shelves. Photo by PD staff.

UPDATE: Since the publication of this article, Mike North has left First Capitol Ag and is now the president of Commodity Risk Management Group. Contact him by email .

-

Mike North

- Milk Marketing Specialist

- First Capitol Ag