Anaerobic digesters have been proven to generate methane, which can be used to produce electricity or natural gas, but dairy producers remain skeptical on whether or not this technology has proven to be profitable.

At the Midwest Manure Summit in Green Bay, Wisconsin, earlier this year, Bob Nagel, dairy manager for Holsum Dairies LLC, opened up the farm’s financial records to demonstrate how they turn a profit with digesters.

Holsum is comprised of two dairies with a total of 8,000 cows.

“We dairy,” Nagel said. “We don’t crop. We don’t haul milk. We don’t haul manure. But we do have digesters.”

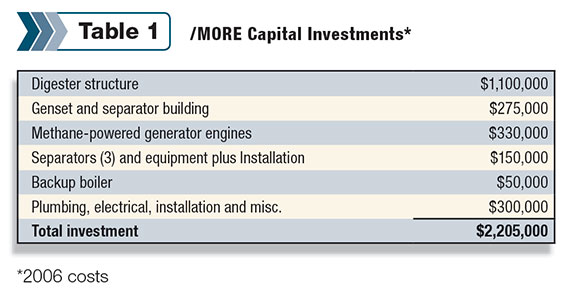

Holsum Irish Dairy was the first of the dairies to install two modified plug-flow digesters, but Nagel focused on the digester built in 2006 at Holsum Elm Dairy for his example. At the time, the total investment was $2.2 million.

To offset the expense, the dairy has a number of revenue streams including: electrical production, bedding, carbon credits, tipping fees, heating and reduced manure application costs.

Electrical production

The farm’s two 600-kilowatt biogas engines run at a fixed rpm of 1,200. All electricity generated is sold to the grid.

To optimize performance, Holsum set up a maintenance contract with Martin Machinery.

The contract pays based on runtime and kilowatts per hour.

“It is in their best interest and ours to get as much electrical production as possible,” Nagel said.

Preventative maintenance is so critical they have both dairies enrolled in the contract and are achieving runtimes greater than 90 percent.

At the time of the presentation, Holsum Elm was generating upward of $900,000 in electrical sales. The costs of maintenance and upkeep were between $200,000 and $285,000 per year.

“When they run and run well, they generate a fair amount of money for us,” Nagel said.

Biosolids for bedding

Three separators run continuously to extract liquid from the fiber material, which is put into the freestalls with a slinger spreader.

“Our cows are very clean and very comfortable, but there are definitely challenges with it,” Nagel said.

He likes the digested solids because they are readily available, provide reasonable cow comfort and traction, are friendly to the manure system and can be a potential revenue stream. If managed well, milk quality can be excellent, he added.

On the flip side, the material is moist when it enters the stalls and will blow around in strong winds. The stall bedding levels are less forgiving than with other materials, and the farm needs to have storage space and actively manage inventories.

Nagel mentioned the market for biosolids has gone up and down. At the time, they were selling solids to five other dairies.

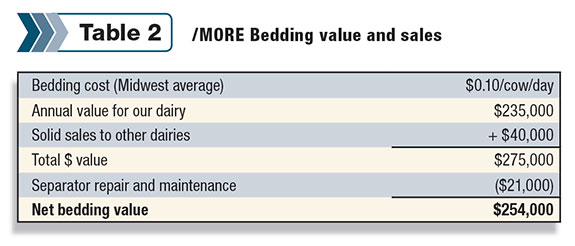

As he ran the numbers, Nagel figured a net income of $254,000 from bedding solids but noted that figure hinges on the quality of the solids.

Carbon credits

Nagel admitted he has a hard time getting excited about the carbon credit market. His two biggest impediments are the hoops you need to jump through and the significant cash outlay necessary before any return.

This process also requires the dairy to monitor methane destruction, calibrate meters yearly and perform a gas concentration analysis quarterly.

An outside broker, certifier and verifier are involved in the process and need to be paid accordingly.

The dairy began selling carbon credits in 2011. In 2012, the farm sold credits to BP to offset the Olympians’ travel to the London Olympics. BP advertised its purchase with pictures of their credit sources in the Olympic Village.

The revenue gained by the dairy after expenses is $104,000 for carbon credits.

“At the end of the day, it’s a nice check to have. You have to be willing to dive into it and trust that it will happen,” Nagel said.

Tipping substrates

In Wisconsin, all substrates need prior approval from the Department of Natural Resources. The Wisconsin Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (WPDES) permit states farms can bring in substrates at 10 percent; however, Holsum applied and received approval to add substrates at 30 percent.

The dairy has learned the hard way that foreign material is a huge concern for digesters. Logistically, it needs to be thought out how the material will be added to the digester. How the material will impact the digester and the bedding solids also needs to be considered.

For that reason, the farm takes in very little grease trap waste. It does take in food processing wash-down water, food and grocery store waste, rumen paunch and a small amount of paper sludge.

The average revenue from tipping fees is $75,000, and that does not include any nutritional benefit the farm may gain on the manure side.

Heating benefits

Excess heat given off by the engines is used to heat the digester, separator room, parlor, holding area, treatment and veterinary area, shop and machinery room, and calf nursery.

Manure management benefits

“(The digester process) does a great job of helping us partition our nutrients to where we like them to be,” Nagel said.

The dairy works closely with area farmers to deliver nutrients to where they are needed most.

Center pivots, as well as a fair amount of drag hose, are used to fertilize alfalfa after cutting. Roughly 60 percent of the manure is used on hay ground.

This has increased yields by 1.5 tons dry matter per acre per year, Nagel said. It also increased longevity of the stand to the point they had to kill good hayfields just to rotate them out on schedule.

The higher solids manure is applied to corn and wheat fields to match nutrient needs.

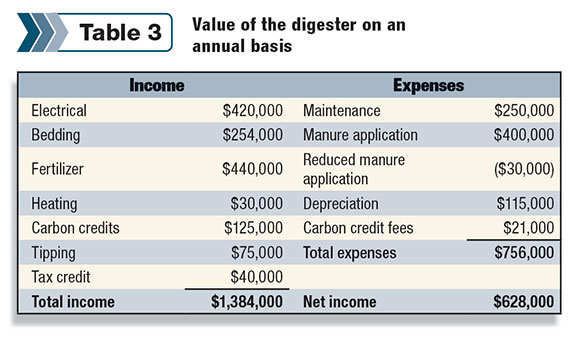

In calculating the value of the digester on an annual basis, Table 3 shows a total net income of $628,000.

This provides the dairy with a 28.5 percent return on investment.

“I think that’s a pretty good number,” Nagel said.

He attributes these profits to dedicated management, good engine run times, the ability to capture the value of the bedding, investment into carbon credits, land base and storage to accommodate substrates, and a willingness to make mistakes and learn from them.

“Digesters do take time to manage,” he said. Even though they are profit centers, “we need to make sure they don’t take away from the dairy, our main revenue stream.” PD

-

Karen Lee

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Karen Lee