Let’s face it; those who have a dairy operation must love what they do. But we are subject to the same marketing principles that apply to other industries: supply and demand.

Throughout our industry’s history, there have been many attempts to address this principle, including federal milk orders, herd buyouts, the Cooperatives Working Together (CWT) program and the market adjustment fee. These attempts to affect a closer balance in the issue surrounding supply and demand have had, at best, only short-term benefits for dairy.

The milk trends for the past 30 years tell a tale of our industry’s heritage. The highest milk prices paid to farmers were as follows: 1986 – $13.40 per hundredweight; 1996 – $16.50 per hundredweight; 2006 – $14.04 per hundredweight; and for the first quarter of 2016 – $15.55 per hundredweight. During this 30-year time frame, milk did escalate for a brief 26-month period to a fair market value just above the $20 per hundredweight range. Perhaps this escalation was due to the reduction of fluid milk from the CWT program.

Yet in comparison, pricing for a gallon of fluid milk is on the rise: 1986 – $2.22 per gallon; 1996 – $2.64 per gallon; 2006 – $3.08 per gallon; and 2016 – $3.30 per gallon.

Today, we all face the same challenge, in a unique marketing scenario with non-dairy competitive products. Our cooperatives have tried to move our excess production, but our prices stay depressed. Can we, the dairy farmer, help in this endeavor? Yes, we can, with a nationwide effort to stop the surplus. We can leave the 3 percent of the current surplus on the farm.

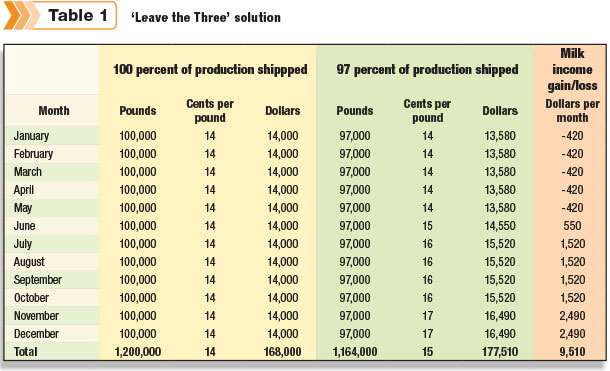

Simple math allows our co-ops to determine the percentage of excess milk. The milk truck driver then applies that percentage to the total pounds in the tank each day and leaves those pounds on the farm for farm use or disposal. In this way each farm sacrifices their contribution to the oversupply. As the percentage values of excess milk go up or down, the percentage values are adjusted to reflect the surplus.

In this hypothetical scenario, the equalization of the supply to the demand should result, with time, in a better price for our product. This type of program, if effective, can then be implemented as a permanent part of our marketing strategy.

Table 1 demonstrates the scenario and the probable benefits as applied.

Dairy cooperatives were born from the need of farmers to create a more successful market for their milk. In that spirit, we, as members, must also contribute by being willing to do what is required according to marketing needs. If our dairy cooperatives do not have the remedy, then perhaps we can suggest that they implement a “leave the three” program. It just may benefit our dairy industry. PD

Cathy Vogl farms with her husband in Harrington, Delaware.