California’s dairy and alfalfa industries are closely linked and face similar challenges, according to Dr. Peter Robinson, department of animal science at the University of California – Davis.

Robinson, a University of California Cooperative Extension dairy nutrition and management specialist, discussed alfalfa at the Purina/Land O’Lakes 2016 Leading Producers Conference held Jan. 5-6 in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. Along with allied industry personnel, the conference drew dairy producers representing 235 herds and 200,000 cows from six states.

In addition to discussing some of the lesser-understood dairy nutritional aspects of alfalfa, Robinson provided Midwesterners with an update on the past – and future – of dairy and alfalfa in California.

“Alfalfa has always been a part of the California dairy industry,” Robinson said. “Since the early days of the dairy industry 100 years ago in the northern San Joaquin Valley to the big expansion in the Los Angeles Basin area in the post-war years (1940s and 1950s), alfalfa hay has always been an integral part of the industry. It can be argued the California dairy industry would not have expanded as rapidly and to such a large size if alfalfa hay, in particular, was not there.”

Robinson said the most recent expansion started in 1997, when the number of lactating dairy cows in California first surpassed 1 million head, and ended when dairy economics “went off the rails” in 2008-2009.

During that period, the number of cows increased more than 70 percent, with the most dramatic expansion in the tri-county region of the southern San Joaquin Valley, including Fresno, Kings and Tulare counties. Since that time, cow numbers have fluctuated between 1.8 million and 2 million, depending on local feed cost conditions and milk prices, he said.

“Dairy growth has essentially stopped. If you run the California dairy movie forward, I see no substantial growth in the short or long term and probably a continuing decline in the size of the industry year by year,” Robinson said. The major reasons for the decline: limited surface and aquifer water availability and competition for land.

“We will continue to see a restructuring of the California dairy industry, away from smaller single-operator dairies to larger dairy business groups, where you have a number of dairies under one group – even as the number of cows declines,” he said.

California’s alfalfa production

Robinson said California’s alfalfa production has been relatively flat since about 1980.

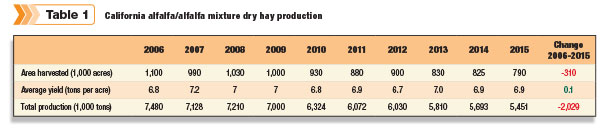

Based on USDA annual Crop Production reports, California’s alfalfa production for dry hay peaked about a decade ago. The state’s acreage devoted to dry alfalfa hay production topped 1 million acres in 2003-2006 and 2008-2009, peaking at 1.1 million acres in 2006. Production totaled 7.48 million tons that year.

A decade later, in 2015, the state’s alfalfa dry acreage was estimated at 790,000 acres, a decline of 320,000 acres from the 2006 peak. So, while average yields remained fairly steady throughout the decade, total production declined more than 2 million tons between 2006 and 2015, to just 5.45 million tons in 2015. Harvested acreage and total production are both down about 15 percent since 2011.

Robinson believes the “hay day” of alfalfa production in the state may have passed.

“I don’t think we’ll see any increase in alfalfa acreage,” Robinson said. “The reasons are multiple and include urbanization, taking land away from alfalfa and competition from other crops based on profitability per acre. We’ve seen extreme expansion in the nut crop industry, particularly almonds, and increases in citrus and truck crop industries. All of those take land away from alfalfa.”

Then there’s water – or lack of it. The Central Valley growing season provides no rainfall in the summer and, combined with high temperatures, means alfalfa production is highly dependent on irrigation.

“With the reduction in the amount of irrigation and aquifer water, and uncertainties on where that is all going to lead in the future, there’s been a reduction in the amount of alfalfa land in the Central Valley. Some of that has been offset in the mountain areas, where there’s a little more summer rain.”

Other factors

California dairy producers have always relied on imports of alfalfa from surrounding states – Nevada, Arizona and even as far away as Utah and Idaho. Those imports are being increasingly constrained by transportation costs.

The state is currently seeing a respite from higher hay prices driven by exports, which had been pushing alfalfa prices up relative to other regions of the country. With slowing economies in the Pacific Rim, alfalfa exports have slowed, and alfalfa prices have come down, he explained.

As a result, California dairy producers have begun stockpiling alfalfa hay in large quantities. One dairy Robinson worked with recently has already stockpiled a three-year supply of purchased alfalfa hay.

“One of the reasons has to do with current lower prices for alfalfa hay – but also the uncertainty relative to water,” Robinson said. “Many of the producers are down to cropping 50 percent of their available land because of water, and there’s uncertainty how many acres they’ll be able to crop in the coming years and whether they can rely on it for a reliable feed source.”

Ration changes

At about 40 percent, total forage inclusion in the high-group California dairy ration has not changed dramatically in recent years, Robinson said. However, the makeup of those forages has changed somewhat, with the role of fresh-chopped alfalfa and corn silage declining. He expects corn silage utilization to continue to decline, replaced by more water-thrifty sorghum silage and winter cereals.

In the past, winter cereals have primarily been used in heifer, low-group and dry cow rations. However, Robinson expects them to play a larger role in high-group rations because sorghum and winter cereals can be grown in California’s two-crop system – water-thrifty sorghum in summer followed by cereals in winter, when natural rainfall is more available.

The forage-to-grain ratio of the dairy ration is also being pressured lower with the availability of multiple byproduct feeds, Robinson said.

“We’re not feeding a lot of grain – primarily corn grain – because the increasing availability of byproducts,” he said. “As we divert land from alfalfa into things like nut crops, we get a lot more byproducts from those industries. We have all these feeds that don’t fit in a typical concentrate-to-forage ratio.” PD

Dave Natzke is a freelancer based in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin.