The effort to bring the California dairy market under the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) umbrella started in 2015 and will certainly end in 2017.

The proposed USDA “Recommended Decision” (Milk in California recommended decision and opportunity to file written exceptions on proposal to establish a Federal milk marketing order) was submitted for publication in the Federal Register on Feb. 14.

The USDA held a meeting on Feb. 22 in Clovis, California, to explain the proposal, and numerous other meetings have been held by state dairy producer organizations and the California Department of Food & Agriculture (CDFA) to review the proposal.

All comments on the USDA proposal must be submitted by May 15, at which time the agency will review comments and make any revisions. Then the USDA will issue a “Final Decision” for a vote among affected California dairy producers or their cooperatives. Approval is required by a two-thirds majority vote or by dairy farmers who produce two-thirds of the milk produced and marketed in California.

Based on current projections, the final proposal will be accepted.

The current USDA proposal for the California FMMO is nearly identical to processes existing in six FMMOs utilizing multiple-component pricing systems.

However, a unique payment system addressing California’s quota system will not be handled by the USDA but rather will be managed by CDFA. The quota system will reduce FMMO minimum prices for non-quota milk, and those funds will be used to increase the milk price for in-quota milk.

The USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) released a report titled “Regulatory Economic Impact Analysis of the Recommended California Federal Milk Marketing Order”.

That analysis uses the AMS dairy model to project the impact the creation of a California FMMO will have not only in the state but also in all other existing FMMOs across the country. Those projections will be the focus of this article.

The existing California system to price milk uses Chicago Mercantile Exchange auction prices to establish the values of cheese, butter and non-fat dry milk. For dry whey, California uses the base price from the USDA’s Dairy Market News statistics.

The FMMO pricing system uses a survey process conducted by the National Agricultural Statistical Service that is broader-based than the Chicago Mercantile Exchange auction prices.

By the AMS analysis, if California becomes an FMMO, higher prices for cheese and dry whey but lower prices for butter and non-fat dry milk will occur. The prices of these dairy commodities are used to price producer milk.

Under the FMMO, the Class III milk price for California will be higher than the equivalent California 4b milk (milk for cheese) price currently in place. The model predicts the higher price will reduce the volume of milk directed to California cheese vats, resulting in less cheese production.

Given California’s large cheese industry, there would also be less cheese produced nationally, which would reduce inventories and increase the price of cheese. By the formulas used to price producer milk, when the price of cheese goes up, the Class III price goes up. Producers in all FMMOs would benefit from the higher price.

The AMS model calculates an increase of 66 cents per hundredweight for all Class III milk. This has a 47-cent-per-hundredweight positive impact on the all-milk price in the Upper Midwest order, where the vast majority of milk goes to cheese manufacturing.

California producers would be delivering less Class III (or equivalent) milk but would receive a higher price for the Class III milk they do deliver. Because of the higher cheese prices, less will be exported and more will be imported.

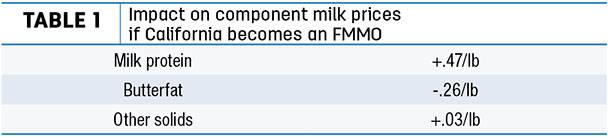

With California delivering less Class III milk, more will be delivered for Class IV production of butter and powdered non-fat dry milk. This will cause the price of Class IV milk to decrease by an estimated 96 cents per hundredweight. This will drive down butter prices by 21 cents per pound and butterfat prices by 26 cents per pound. More butter will be exported; less butter will be imported.

Nonfat dry milk will decrease in price but by less than 1 cent per pound.

But even with this small decrease in price, exports are expected to expand. Nonfat dry milk is the largest U.S. dairy export, and by this analysis, it will increase if California becomes part of the FMMO system. These increased exports must find an international market for the additional powdered nonfat dry milk/skimmed milk powder.

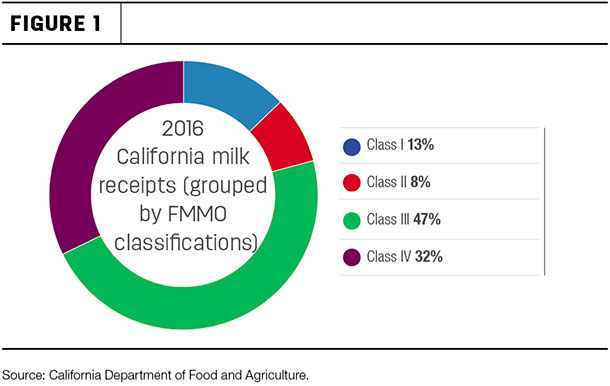

Figure 1 shows the 2016 California milk production by the four FMMO milk classes. In 2016, Class III milk for cheese was the major use of California milk.

By the AMS model, the Class III usage would shrink and the Class IV usage would increase. This change will probably not be evident until 2018.

With relatively less cheese produced, less whey will also be produced. Therefore, the price of whey will increase. The model predicts a small increase in the price of whey that is dried. When dry whey goes up in price, so does the value of other solids, so the AMS model shows a small increase in the value of other solids. All FMMOs paid on the component basis would benefit from this increase.

It should be mentioned that the value of nonfat dry milk and dry whey is primarily determined by international factors, so the change in this model will likely be difficult to track as international events will have a much greater impact.

When cheese is more valuable and butter is less valuable, milk protein increases in value from both events. (The FMMO pricing formulas work this way.)

The AMS model predicts an increase in the value of milk protein of 47 cents per pound. This is a very powerful shift for California producers, who will be paid specifically for milk protein as opposed to solids not fat and will be paid at a higher price for that milk protein. The increased value of milk protein also has a strong impact on the existing FMMOs.

Overall, the AMS model projects a very positive financial impact for most all U.S. dairy producers if California elects to become a FMMO. Who pays for this? The answer is: the U.S. dairy consumer. The U.S. dairy consumer would pay an additional $94 million on the purchase of dairy products. Cheese and fluid milk would become more expensive while butter would become less expensive.

Cheese and butter are increasing in per-capita consumption. This could slightly decrease the growth in cheese consumption and accelerate the growth in butter consumption. Fluid milk consumption has been decreasing for decades, and a higher consumer price may accelerate this decline.

The AMS model is a very sophisticated tool, and the impact analysis should be taken seriously. That said, there are so many other influences on the wholesale and retail price of dairy products the real results of California becoming an FMMO can never be accurately tracked.

The most volatile changes in dairy prices come from changes in exports and imports of dairy products. International events can influence the international supply and demand forces for dairy products. And currency exchange rates can significantly influence the financial competitiveness of U.S. dairy products in the international markets.

Under the current California pricing process, producers cannot depool their milk. However, as an FMMO, depooling will be an accepted practice. In the Upper Midwest order, depooling is common when the Producer Price Differential goes negative. The depooling significantly distorts the analytics of milk production and usage.

That means that, at times, some California milk production may not be reported through the FMMO process, making tracking numbers more difficult. The data in the AMS report anticipates some depooling for Class II, III and IV milk. Class I cannot be depooled.

California producers are the ones who will approve or reject the change to an FMMO. There seems to be no reason for producer rejection based on the AMS analysis.

There is also no reason for dairy producers in the existing FMMOs to lobby against this change. For these reasons, it is very likely approval will be given. The transition will then take months before completion and real results occur. ![]()

-

John Geuss

- John Geuss Consulting

- Email John Geuss