These are difficult times in our industry. Reduced milk prices are putting severe stress on dairy businesses and encouraging greater emphasis on total costs of production as opposed to milk revenue.

Despite the need to watch costs closely, we need to keep in mind the ultimate goal should always be higher profits, not lower costs.

A very real question you may be considering is “How much can I cut back without falling behind?” If that’s crossed your mind, the key is to find the right balance between investment and expenses. That analysis starts by understanding the cost of maintenance and then evaluating investments to drive greater production beyond that point.

Maintenance is primarily the feed required to keep cows healthy and producing. This requirement won’t change much; whether she produces 75 pounds of milk or 85, the maintenance is generally the same. What’s beyond that base investment in maintenance is what we call marginal milk. By understanding marginal milk, producers can maximize their investment in feed and make better decisions in their nutrition program.

Marginal milk is the cost and net revenue from the next additional pound of milk produced. At that point, maintenance and fixed costs are accounted for because the cow is already in the barn, the milking parlor is running and so forth. Fixed costs stay the same whether the herd averages 75 pounds of milk or 85. We pay incrementally for each additional pound of milk the cow makes beyond the maintenance level. Marginal milk allows us to look closely at what an extra pound or two of milk would return if you fed for it. Conversely, if 1 or 2 pounds of milk were sacrificed to reduce feed costs, what would be the net gain or loss from that decision?

The higher the production, the more we get for the investment in her maintenance cost. It’s like going to an amusement park; the entrance fee is the same regardless if you stay for an hour or the entire day. Increasing feed and production makes sense theoretically until the rate of return falls under 1 to 1. Practically, most experts agree that taking production up makes sense until the rate of return falls below 2 to 1, accounting for potential errors and providing a safety margin.

To evaluate changes in production correctly, it’s important to recognize the difference between marginal costs and average costs. Average costs include the feed for the next pound of milk as well as the fixed costs. We should not use average cost in this analysis because the maintenance cost is already paid for. We are just examining what would happen if we spent, or saved, the money to add, or lose, milk income. Using the wrong number can prevent us from making changes in production that would improve profitability.

We also need to remember that cows have a requirement for nutrients, not feed. If we focus solely on the cost of the feed, without considering its nutritional value, we could end up paying more in the long run for the maintenance cost. Oftentimes, it’s worth paying more for nutrient dense feed that cows can consume less of to make more milk components. The nutrients in the feed are what ultimately drive production and components.

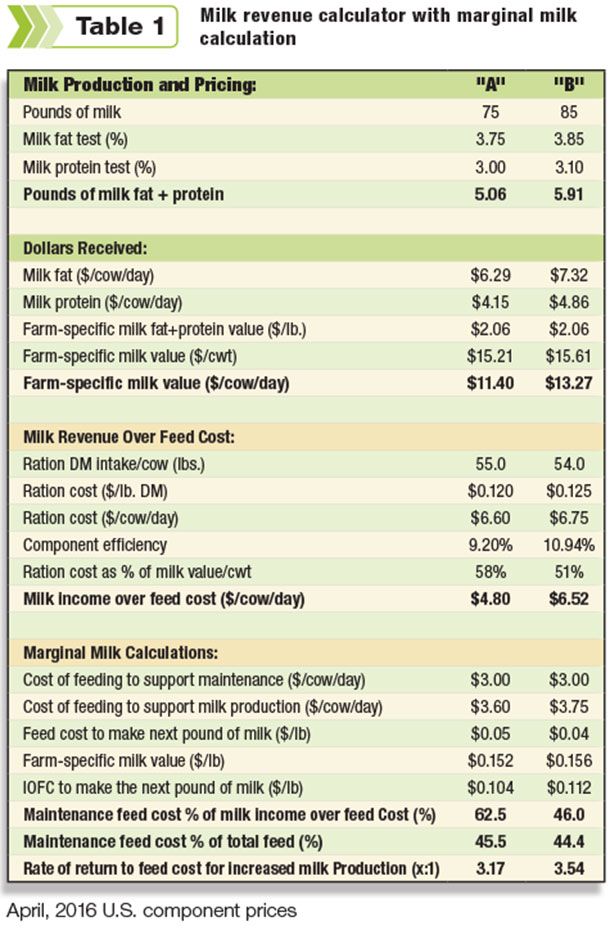

The Cargill Milk Revenue Calculator with Marginal Milk Calculations (see Table 1) is an example of a tool that was developed to evaluate decisions like this.

The calculator analyzes farm specific numbers to help producers understand the value of increasing or decreasing production and components. In the example in the chart column “A” is the herd’s current status. They are producing 75 pounds of milk with total components at 5.06 pounds. Their current ration is formulated on ingredients and focuses on cost of inputs over nutrients delivered, resulting in a dry matter (DM) intake of 55 pounds per cow, making the ration cost $6.60 per cow per day to meet her nutrient requirements; component efficiency, which is a measure of pounds of components divided by DM intake, is 9.2 percent. The marginal milk calculations show us the percent of the feed cost going toward maintenance is 45.5 percent. The cost to feed for maintenance as a percentage of net milk income over feed cost is 62.5 percent. It would cost an additional $.05 of feed to produce the next pound of milk with the same components, resulting in a return on investment of 3.17 to 1.

Scenario “B” looks at what the potential could be if we formulated the diet to focus on delivering the necessary nutrients at the best cost. By focusing the diet on nutrients that make components efficiently, the DM intake per cow drops to 54 pounds, but the cost per pound of DM increases; as a result, the ration cost increases $.15 to $6.75 per cow per day. Production and components increase, and component efficiency improves to 10.63 percent, meaning the cow is becoming more efficient at turning feed into components.

Components are what ultimately increase the milk income over feed cost (IOFC) to $6.52, which is why the efficiency has improved. In this case, IOFC is $1.72 higher, even though we are paying $.15 more in feed cost, which is a net gain. The percent of the feed cost covering maintenance in this diet is now 44.4 percent. The cost to feed for maintenance is now only 46 percent of the net IOFC, a vast improvement compared with 62.5 percent. The marginal milk calculations show the next pound of milk, with these now higher components, would cost an additional $.04 of feed, resulting in a return on investment of 3.54 to 1.

As we can see, the nutrient content of what we are feeding the cows is a critical factor. To be profitable, producers must look beyond the cost of an ingredient and analyze the ability of the nutrients they are paying for to produce pounds of milk components. We will always have to feed cows to produce milk, but how we maximize that investment can greatly impact a herd’s profitability. When discussing ration changes with your nutritionist, the impact to marginal milk production and components should always be calculated to understand the economic impact of the change. PD

Kurt Ruppel is the technology leader for Cargill U.S. Dairy Services.

PHOTO: Staff photo.