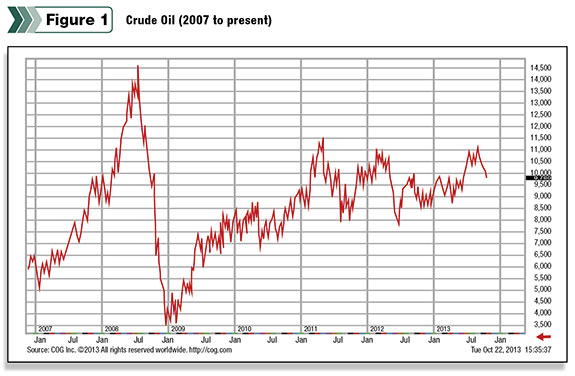

It has been long said that the cure for high prices is high prices. This wisdom can generally be applied to about any market one looks at. When crude oil prices spiked to $147 per barrel in 2008, it was only a short time later that prices were back below $50 per barrel.

Five years later, the market has had a difficult time moving beyond $100 for more than a few months at a time before returning to $80 per barrel. While one could easily argue that $80 is not a low price, it is a far cry from $147.

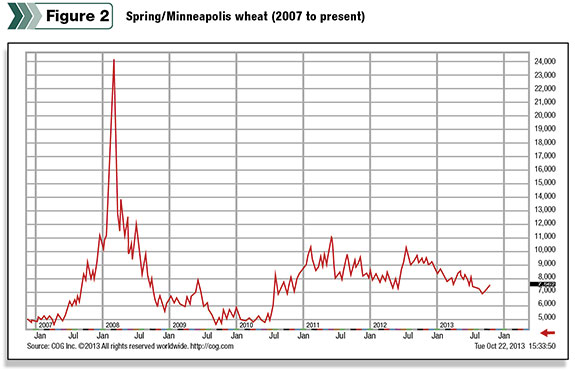

This is true in other markets as well. Months before the economic bubble burst in 2008, spring wheat prices surged to a level of $24 per bushel. By the time the rest of the economy began working lower, wheat had already returned to levels south of $8 per bushel.

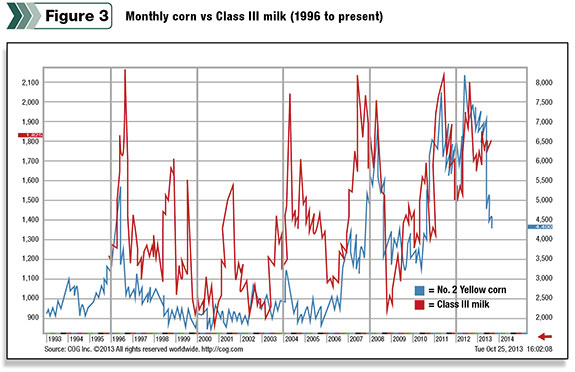

Like crude oil and wheat prices, corn and milk also experience such responses. After corn prices move higher, corn prices move lower. For dairymen, it is interesting to observe the relationship between corn and milk as they move up and down.

If corn prices move higher in an extreme fashion, milk prices tend to amplify that behavior. When corn prices move lower, milk prices again will follow its lead. Taking a closer look, it is easy to see the relationship between the two.

See Figure 1 . We have long talked about the three-year milk cycle being impacted by oversupply and undersupply of milk and the impact cow physiology plays into it.

When we inject corn price into that conversation, we do not introduce an interrupter to that cyclical course of price movement, but rather an amplifier.

Looking back over history, we notice that corn usually takes the lead.

When corn upwardly breaches the $3 threshold, milk prices have historically performed incredibly strong – each time surpassing $20 per hundredweight (cwt).

As corn prices move below that level, high prices tend to become more subdued as witnessed in the 1990s and the turn of the century.

The relationship between a lower-moving corn market and a declining milk market also

produces some interesting observations.

In each of the previous major price declines in corn (50 percent decline in price from the peak), milk prices also have fallen substantially.

While there is not a strong enough correlation to predict where milk will go, the hard truth is that a big fallout in corn price historically suggests coming declines in milk price to be amplified in its move downward.

For years, this hasn’t been much of a concern as corn prices have not seen below-$3 levels since 2009.

An additional observation is one of timing. The tendency of a milk market to move lower after witnessing a lower movement in corn is very strong. Historically, every time corn has gone above $3 per bushel and later found its peak, the summit in milk has only been two to three months away.

The most recent peak in the monthly corn continuation chart took place in August 2012. The most recent high in milk price followed in November, just three months later; in all previous occasions, the time lapse was only two months.

Since the peak in corn, prices have continued to work their way lower as larger yields and fatter balance sheets led the way toward $4 per bushel. Milk has worked lower as well but with a much tamer attitude so far.

So what’s the bottom line? The reality is that corn prices have worked lower. While dairymen around the world work to backfill global product tightness, the return of less costly feed will be welcomed with open arms, or bunkers as it is. What we all know about cheaper corn is that it gets fed … and more abundantly. This leads us to the obvious result: more milk.

Milk markets have already established pricing at lower levels in expectation of greater production. However, what we haven’t established is what the consumer will do going forward. Milk prices have largely been sustained by the tug-of-war between Asian product interest and shortened New Zealand production.

Will the return of cheaper feed and expectation of greater production cause buyers to relax their aggressive efforts so as to capitalize on lower prices? It is incredibly possible.

The bottom line in all of this is simple: Less-expensive feed has historically always been a precursor to cheaper-priced milk. The question one must ask is this: “Am I ready for such a move?”

As you prepare for 2014, keep this relationship in mind. Talk with your risk management adviser to develop plans and strategies to address this situation. While cheaper corn is welcomed by the dairyman, cheap milk is not. PD

UPDATE: Since the publication of this article, Mike North has left First Capitol Ag and is now the president of Commodity Risk Management Group. Contact him by email .

Mike North

Senior Risk Management Adviser

First Capitol Ag