How do you know when a dairy cow is happy? Does she smile at you? Do a little dance? Wag her tail? Doubtful you’ll ever get that sort of positive feedback from cows. I’d venture to say that the first and best way to tell if your cows are happy is to see how much milk is in the milk tank. You all know how much milk is supposed to be in the milk tank every day and when it’s up a little – that’s a good thing.

But when it’s down a little – well, you’re normally not happy about it – and I’d say the cows are reacting to something, as well.

Dairy cows have essentially three really important things they have to do every day besides the obligatory time being milked. For the rest of the day cows must eat, rest and ruminate. When any one of those three things are disrupted for any reason, milk production will suffer.

If you don’t feed cows on time or they don’t get the proper ration, milk production suffers. If they spend too many hours on their feet and are not allowed to lie down and rest and ruminate, milk production will suffer. Along with that, too much stress and/or a dirty barn often lead to mastitis and milk quality issues.

Dairy facility design is a critical element of whether cows are comfortable and allowed to eat, rest and ruminate to their optimum each and every day. And having cows clean when it’s time to milk them makes that chore much more tolerable, too.

Volumes have already been written on how to best design barns for either freestalls or bedded pack housing along with the alleyways, barnyards and feedbunks that must accompany them. Today’s dairy facility designs must keep cows clean, dry and comfortable while incorporating features that support environmental sustainability and legal nutrient management.

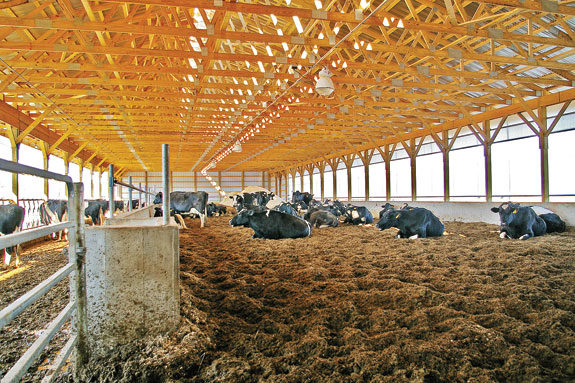

No herd of cows was more happy to move into their new bedded pack barn than Tex Moon’s cows were in October of 2011. Located in Bozrah, Connecticut, Moon had decided to replace his 1960s-era freestall barn, which had seen better days, with a new and up-to-date facility including lock-up stanchions at the feed manger.

The old barn was razed during the summer and the new construction began the last week of August, which happened to be the same week that Hurricane Irene decided to invade Connecticut. The following week Tropical Storm Lee added to the misery and, together, the two storms dumped upwards of 2 feet of rain on the Connecticut landscape.

During the construction and the inclement weather, the 40 or so cows in Moon’s herd were denied shelter and were becoming more miserable with each passing day. Milk production was headed south, too. Remember: Eat, rest and ruminate.

Finally, the barn was complete and ready for occupation – just one day before a freak October snowstorm dumped over a foot of heavy, wet snow on much of the state. Moon said you could almost hear the cows breathe a collective sigh of relief when they walked into the freshly bedded barn for the first time and immediately laid down.

Within a matter of days, milk production started to recover.

“My main goals for choosing the composted bedded pack barn,” said Moon, “were for cow comfort and not having to deal with a liquid manure system.”

In February of 2012, Moon was still getting the feel of how best to manage the pack, keeping the temperature optimal for good composting with the goal of taking that compost and spreading it over pastures and corn ground this spring. He turns the pack daily with a cultivator and adds about three inches of wood shavings every week.

He’s pleased that the pack is doing what it’s supposed to do because organic material actually shrinks as it’s converted to heat energy.

“[The pack is] not building up with manure like I thought it would,” said Moon. “So far after three-and-a-half months, the pack is about 18 inches deep. I’m anticipating another two-and-a-half feet in the next two-and-a-half months, which I don’t think is that bad.”

Moon has concluded that the moisture level in the pack plays a big role in how it heats. He has found that the pack heats to about 100 degrees when the moisture is somewhere around 40 to 60 percent. The trick is learning how to keep it in that range.

The new barn covers an area of 176 feet by 50 feet with the bedded area 125 feet by 38 feet, intended to accommodate 50 cows. The barn is contiguous to the herringbone milking parlor, which is just a few years new, as well. The herd is currently producing a daily average per cow of about 64 pounds of milk with 4.2 percent butterfat and 3.2 percent protein.

The somatic cell count stays between 130K and 150K, and mastitis is virtually non-existent. Moon and his wife, Sarah, are licensed to sell raw milk from their dairy.

Cow comfort was a major emphasis for David Hyde when he purchased a dairy in Franklin, Connecticut, in 2006 and renovated it in 2008. He built a 65-foot by 170- foot barn designed to accommodate 50 cows. On one end of the barn is a spacious concrete holding area, about 30 feet wide, leading to the flat, in-and-out style milking parlor.

On the opposite end of the barn is a dry manure storage area. The barn was built also with maximum ventilation in mind, but Hyde did have to put up curtains on the windward side to protect the barn from the frigid winter wind.

Hyde planned for 100 square feet per cow, but said it really wasn’t enough. He feels 125 to 130 would have been better for optimal square footage per cow. He roto-tills the pack every day and adds sawdust every other day. He points out that this kind of barn is not as labor-efficient as a freestall barn.

“It takes a lot of labor to maintain the pack,” said Hyde. “With freestalls we used to go in and bed them twice per month and kick the manure into the lane when we milked. If you miss a day [with the roto-till] the cows are dirty.”

But, of course, on the plus side there’s no liquid manure to deal with.

The pack is allowed to accumulate for a year and is removed during the spring. Last year Hyde estimated he removed 500 yards of material from the barn. He states that managing the pack is an on-going learning process.

He still has trouble getting the consistent desired heat from his pack. It takes the right combination of sawdust and moisture to make it right. “Some days it will heat and other days it doesn’t,” he said.

But the cows like it. The somatic cell count in Hyde’s herd stays down around 120K since the switch to the bedded pack and mastitis is rarely an issue. The herd has an annual rolling herd average of about 22,500 pounds of milk.

Debates will no doubt continue over which dairy design is the best. The most successful dairies will eventually be those that can optimize milk production and produce a high-quality product with healthy cows while being environmentally sustainable and effectively avoiding pollution.

Depending on size and geographic region, many dairies will find that the composted bedded pack housing offers a very workable means of keeping cows comfortable, healthy and productive with the added benefit of utilizing the natural process of composting manure, making it more efficiently available for recycling. PD

PHOTO

Dairyman Tex Moon’s recently completed bedded pack barn in Connecticut has improved cow comfort. Courtesy photo by John Hibma.

John Hibma

Nutritionist

Central Connecticut

Co-operative Farms Association