This theory still holds true, but over the years, we have been seeing a bigger role for the part that fiber plays, the type of fiber, and more importantly, how this is processed in your mixer wagon.

Research in the area of total mixed rations (TMR) has shown differences in performance that were unexplained by energy, protein, minerals and other nutritional parameters. There are various chemical and physical factors, such as the particle size of the feed, which affect rumen fermentation and as a result influence milk production and composition.

While harvesting forages at the proper chop length is critical, additional attention should be paid to the process of feed mixing, as it may result in large effects on diet particle size and uniformity. In simple terms, we were beginning to see that the type of fiber and the way this fiber was processed in the TMR mixer were influencing overall production of the animals.

On-farm studies over a number of decades have showed a 1.1-pound (0.5-kilogram) increase in milk with 1.5 pound (0.7 kilogram) less dry matter intake (DMI) after mixing the exact same diet and ingredient proportions in two different ways. This backs up the hypothesis that balancing your ration is important, but the quality of the mix you produce is equally as important. This has been further supported with a study carried out at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom. We know the optimal rumen pH is 6, and this research showed the pH of the rumen of the animal could be kept above 6 for 33% longer by using the exact same diet in the same proportions but just by mixing the diet in two different ways.

These changes can be linked back to the effectiveness of the fiber contained within the TMR mix rather than just the length. Some of the diets outlined above had fiber components, such as straw and hay, that were much longer than would be considered normal. These diets had 2% to 4% of long fiber processed to 1.18 to 2.76 inches (3 to 7 centimetres), depending on the forages being used in conjunction with them. As previously outlined, cows were milking more and eating less, resulting in an overall improvement in feed efficiency. This has a direct affect on margin, compared to maximizing DMI to achieve better milk yields.

It was becoming quite clear there was a distinct difference between the NDF fiber and the physically effective fiber (peNDF) in the diet. A term sometimes called “scratch factor” was used when describing a diet that was more physically effective. This physical effectiveness stimulated the rumen, which caused the rumen to contract, mixing the contents and stimulating cud chewing. Increased cud chewing generated more saliva and thus more buffering capacity for the rumen.

Another way to show the effect of the scratch factor would be to see the difference between straw and soyhulls. They both had similar NDF levels, but one was more physically effective compared to the other. It is now understood that if we could retain the structure and consistency of this ingredient within the TMR mixer, this would allow us to create a stable rumen environment. This stable rumen environment has been shown to achieve 10% more production from the same amount of feed through greater feed efficiency by just maintaining the effective fiber in our TMR mixes.

Effective fiber is not new, and Mertens in 1997 related chewing activity to both NDF concentration and particle size, and proposed the concept of peNDF, which is fiber that could have a physical effect on the rumen of the animal. This research backed up the previous work that particle size is the major factor determining peNDF, but the length of this fiber was important because putting in long fiber that animals sort out and do not eat will not solve the problem or create an improvement.

Also, the concept of peNDF was originally defined from an analytical perspective as the proportion of the original sample NDF greater than .05 inches (1.18 millimetres), whereas some would have counted peNDF as that which is more than 1.18 inches (3 centimeters). To reiterate a previous point, while effective fiber involves the length of the fiber, it also relates to fiber type, chop type and its overall consistency and distribution in the diet, on which the mixer wagon has a major effect.

There has been further research in recent years to support the concept of physically effective fiber, its length and its importance in rumen function. Beauchemin (2008) fed small amounts of cereal straw (greater than 1.1 pounds per day) as a source of structural fiber. When straw of suitable length (1.57 to 3.15 inches) and structure was fully incorporated into mixed rations, encouraging animal performance results were noted. In contrast, providing soft ryegrass straw as a ground-pelleted or coarse-chopped cubed feed to cows grazing high-quality pasture showed no positive effects on milk production, milk composition, rumen pH or time spent ruminating per unit of DMI.

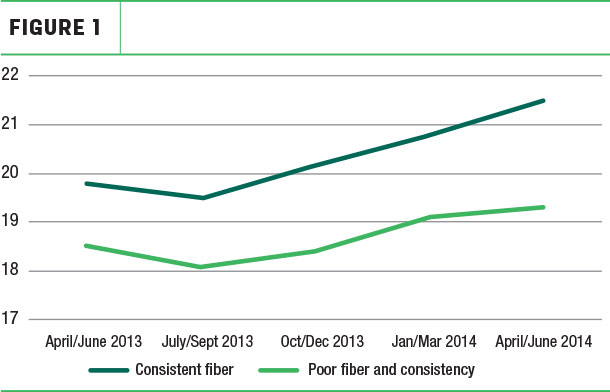

Also in a study of 600 U.K. dairy farms with TMR feeding, all-year-round calving, similar days in milk and a nutritionist to balance their diets, the farms having more control over chop type and consistency in their TMR mixer produced more milk. As shown in Figure 1, the increased milk over a full lactation was 1,373 pounds or an extra 99 pounds of milk solids per cow.

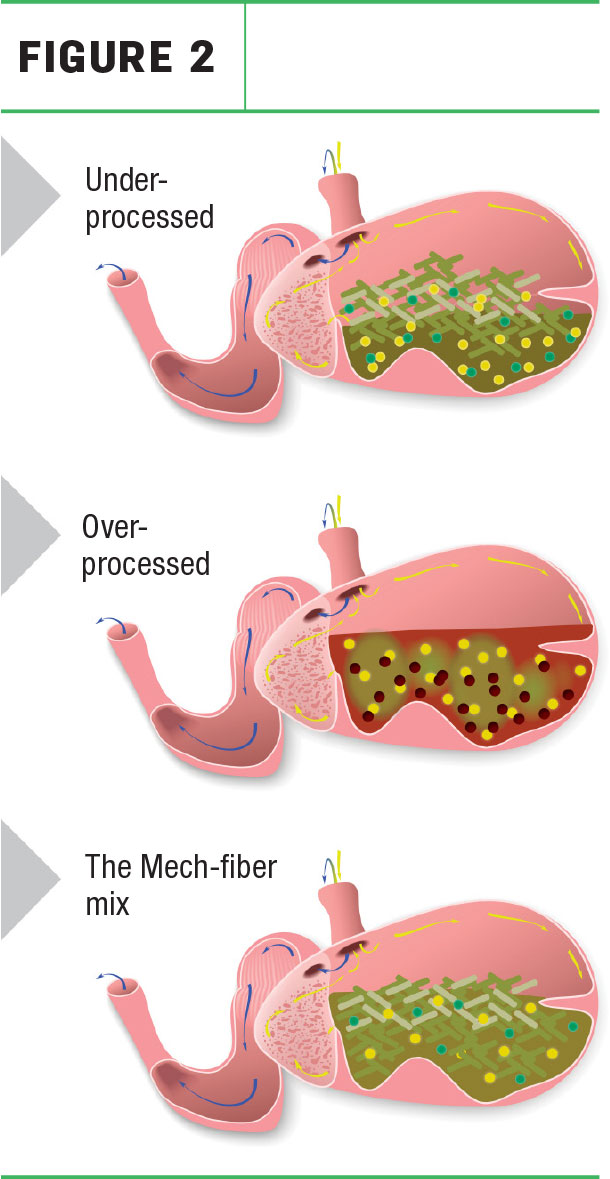

The next step in the journey was to understand what this effective fiber was doing to the animal or, more importantly, the rumen of the animal. Figure 2 gives us an overview of what is happening when we supply under- and over-processed fiber in an inconsistent way to cows as opposed to a mix that adheres to ideal principles for length, type and consistency in the mix.

As we strive for higher levels of production, there has been increasing emphasis placed on achieving higher quality and digestible forages. The fiber content of these forages now acts more like soluble carbohydrate, so there is a need for effective long fiber to be added. These outlined results confirm the importance of mix quality in the ration to achieve optimal rumen function. When suitable long fibers, such as straw or mature hay, are correctly processed and incorporated into well-mixed rations, minimization of sorting ensures more consistent ration consumption.

There are generally three diets fed on the farm: the one the nutritionist created, the one the farmer thinks he or she fed, and the one the cows actually eat. These can be very different diets on some farms, which is concerning. To reduce this error on farms, we need to constantly review and check the following in the mixing process:

1. Working condition of the mixer wagon – blades, weighing system, etc.

2. Loading order of ingredients

3. Margin for error in the loading of individual ingredients

4. Mixing times

5. Post-examination of TMR feedout for:

a. Moisture level

b. Chop length and type – is there effective fiber in there, not just NDF?

c. Consistency – Penn State separator

d. Sorting present during the following 24 hours

e. Residuals and refusals

We know fiber plays a major role in the health of the rumen and thus the animal, but it also has a major role to play in the production of the animal. Fiber is not just about NDF, it is about the fiber type, chop length, chop type and overall consistency of the mix, or more importantly, how “effective” this is. Your mixer wagon and operator play a major role in maintaining fiber through the mixing process, and only until we achieve this can we truly reach the potential of our diet. ![]()

PHOTO: Cattle at the feed bunk. Courtesy photo.

For further information, contact Nathalie Thibodeau, Alltech customer service representative, at (450) 253-0779 or email Nathalie Thibodeau.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Cathal Bohane

- Head of InTouch Nutrition

- Keenan

- Email Cathal Bohane