Think back to the last cow you sent to market. If you peeled back her hide, what would you find? Bruising? Injection site lesions? Tissue damage? Would you be proud to say that cow came from your dairy?

A group organized by the Professional Dairy Producers of Wisconsin (PDPW) recently went “behind the hide” to gain a packer’s perspective at one of the nation’s largest dairy cull cow processor plants.

“It’s not just disposal of your old cull animals,” Casey Davis, head of JBS Green Bay cattle procurement, emphasizes to dairy producers. “You are a part of our beef industry.”

With U.S. cattle inventory at its lowest point in decades, the dairy industry’s contribution to the beef supply is more valuable than ever. Cull cows have a place in providing quality muscle cuts in addition to lean beef. However, when carcasses come through with damage, both the producer and the processor are missing an opportunity for profit.

Carcass damage

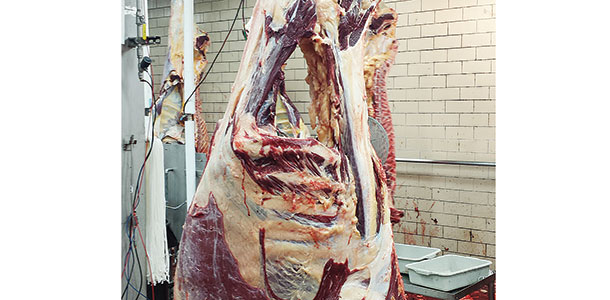

If you think animals in this condition are few and far between, think again. Nearly 1,000 dairy cull cows come across the line at JBS’s Green Bay plant daily. On average, one out of every five has visible carcass bruising.

The damage may have occurred on the farm, during transit or at the plant. Bruises might be caused by cattle bumping into corners, objects and other animals, or they may be the result of poor animal handling.

Bruised areas must be trimmed out of the carcass. These trimmings have no value as a product for human meat consumption and are sent to rendering or used in pet food. When damage occurs in a higher-value cut like the loin, the entire muscle is then devalued.

Damaged carcasses were costing JBS an estimated $11,000 each day between lost meat value and production time, according to Davis.

These costly consequences prompted JBS to take a closer look at why, where and how bruising occurs. That effort was led by Dr. Lily Edwards-Callaway, animal welfare, technical services, for JBS USA, LLC.

Edwards-Callaway initiated a research study that followed 320 live animals through slaughter at two JBS plants handling dairy cull cows, including Green Bay. Cows were scored for lameness, body condition, udder condition and lesions. Then the carcasses were assessed for bruising, noting the location of the damage, estimated age of the bruise and amount of meat trimmed.

“Our study revealed that on average we were losing approximately 7 pounds of trim per animal to bruising,” Edwards-Callaway says. “That is an inefficient use of the animal and decreases the amount of edible product we can provide to customers. Our team made it a priority to reverse this trend.”

Most commonly, bruising was found along the back and on the loin and round, areas that, when intact, can capture a higher saleable value. Bruise coloration was used to determine when the damage likely happened. “Ten to 24 hours prior to slaughter seemed to be when most bruising occurred,” she adds.

Because cattle spend on average 10 hours at the plant before being harvested, this data could have been interpreted to say that activities resulting in bruises were going on prior to arrival. However, JBS chose to accept responsibility for the steps in the process that they could control internally. This included observing cattle transportation and unloading, as well as evaluating cattle facilities and handling at the plants.

The study watched animals as they unloaded from the trucks upon arrival at the plant’s barns. In some cases, taller, bony cows were bumping their backs as they came off of the truck. Loading density also seemed to affect bruising when weaker cows were pushed or bumped by other cattle.

According to Edwards-Callaway, JBS has reached out to cattle truck drivers to educate them on how they can prevent bruising during the time the animals are in their care, and their suggestions have been met with a positive response.

“The truck drivers are definitely interested in improving handling,” she adds. Such suggestions include mapping out a route from the pick-up point to the plant that minimizes bumpy roads, short-stopping and repeated turns.

As animals arrive at the plant, Edwards-Callaway says the goal is to move them quietly and calmly. Her research looked at corners and turns through the barn where bumping or crowding could cause bruises. To correct this, the problematic areas have now been padded.

Other modifications are made as necessary to improve the barn environment. For example, in the holding area leading up to the chute, a crowd gate guides animals forward while a hose blows just enough air to make a noise to urge the cattle ahead.

Audits are performed routinely to ensure barn workers are following the American Meat Institute’s guidelines for humane handling. AMI guidelines state that it is acceptable to use electric prods (in accordance with protocol) at the entrance of the restrainer on up to 25 percent of cattle entering through. However, observations at the JBS Green Bay found that plant’s usage to be less than 5 percent.

Edwards-Callaway attributes this statistic to the “good culture of animal welfare” supported by the leadership and management of the plant’s yard supervisor, Don Campbell. “He is one of those people who truly cares about animals,” she says.

The focus on minimizing bruising on behalf of the plant has resulted in improvements.

“As we focused our efforts on tracking carcass damage and potential causes, we have been able to demonstrate significant improvements in carcass quality, utilization and cattle comfort,” she adds.

How to capture greater cull cow value

JBS is taking their message of minimizing carcass damage a step further by reaching out directly to dairy producers to educate them on how to capture more value from their culls. Edwards-Callaway encourages producers to consider “timely euthanasia.”

Waiting until the last minute to ship a cow may mean that by the time she gets to the plant, she will not pass the live or post-mortem inspection, or she may be at high risk for going down in the truck or in the barn. These situations are not profitable for the producer or the processor, nor are they doing what is right for the cow.

“Send cows to slaughter before it is too late,” she stresses. “If you know that animal is not likely to recover and will have to be culled, send her to market sooner. It is better for her welfare and for our industry.” PD

PHOTOS

TOP, MIDDLE: One out of every five dairy cows coming through JBS’s Green Bay plant has some type of carcass damage that requires meat to be trimmed away. The loss of value on these trimmings, which must be downgraded to use for rendering or pet food instead of for human consumption, was costing JBS $11,000 every day as of April this year. Photos courtesy of JBS.

BOTTOM: JBS Green Bay’s yard supervisor, Don Campbell, has more than two decades of experience handling live cattle as they arrive at the plant’s barns. While he may look as though he is playing catcher at a baseball game, this required safety gear protects him from the potential dangers of his job. Photo by Peggy Coffeen.

Peggy Coffeen

Editor

Progressive Dairyman