There are many theories as to why milk prices have gone higher since the lows of 2009. Some will argue that the CWT cow kills removed enough production capacity so as to shorten the available milk supply for processors, thus raising their effective bid. Others will make a case for growing export demand and the broad sweeping interest that foreign buyers have for our products. Some will bring up the crippling weather conditions experienced throughout the Oceania region that shortened their feed availability and ultimately their milk supply.

Many will point out that there was a shortage of quality forages following the 2009 harvest, causing lesser milk output. Some will point towards the high price of feed and the resulting tightening of rations which led to lesser production by the national herd. Still others will point out the record tightness of butter supplies.

Many will suggest milk prices must always follow feed prices in order to maintain at least a survival level of profitability at the farm and complementary balance of production. Additionally, there will still be others who will discuss the impact of speculators in our marketplace and the effect they have on price.

I would dare to say that all of these things have had at least minimal or momentary effects on the market and have helped to buoy prices from near-record lows in 2009 to levels that now scratch what has become the imaginary lid on milk prices.

But are all of these incidents independent of themselves and isolated to some other force at work? Or could all of this be a part of a bigger trend? Could there in fact be something greater at work? I would suggest there is.

I have mentioned the “three-year milk cycle” and its haunting ability to create a measure of predictability about price direction. Of course, no one can be absolute about a market … especially these days.

However, time and time again, the milk market has shown its ability (despite the prevailing circumstances, discussions or otherwise) to repeat itself and move from low price to low price approximately every three years.

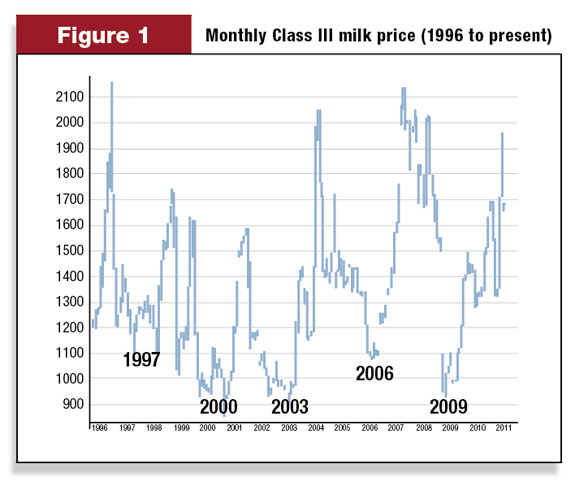

Please refer to Figure 1 . A quick review of history shows a low made in 1997, then again in 2000, followed by another low in 2003. This low was followed by a low in 2006 and then in 2009 we fell sharply back to what many will refer to as the hardest-hitting prices of all time (even though it did not set a record).

In reviewing this information, I would suggest that 2012 may be suspect for experiencing a move back to these same low levels. As is plainly seen, the market tends to move back within the range from $9 to $11 per hundredweight (cwt) when establishing its lows.

Have you begun making preparations for decreased revenues in 2012? Or have you begun to address prices to shore up current opportunities? Will you be ready?

Several strategies exist for dairymen who are seeking to address the potential 2012 revenue shortfall. Before we discuss any of these strategies, let’s make sure we are perfectly clear about something far more important, that being the subject of margins. This, too, has been a long-held subject in our discussions with dairymen.

Be sure to address feed costs and other inputs when planning/locking/protecting your revenue for the coming year. You do not want to be caught in a one-sided milk strategy, only to have the cost of feed run you over. If you have questions about addressing feed prices, talk with your feed vendor, nutritionist, silage supplier, etc., or call your broker.

The bottom line is to make sure to address the margin by addressing the components that affect it, not just one of them. However, since this discussion is about milk, we’ll address that component here.

At the time of this writing, Class III milk prices covering the last half of 2011 and the first half of 2012 average $16.87 per cwt. Looking at it from a different angle, the last half of 2011 averages $17.54, while the whole of 2012 averages $16.11.

A quick look at these levels makes it very clear that we are not at the all-time highs witnessed in the past 30 years. However, they surely beat the pants off of $10 per cwt.

Producers really have two options at this point. One of those options is to sell your milk either with your milk buyer (if such an opportunity exists) or sell milk futures to lock in those very same price levels mentioned previously. Be sure to check the costs and other commitments associated with selling to your buyer with the costs associated in using futures.

Bear in mind that there will be cash flow requirements for using futures, referred to as margin. You may forfeit money to the market in order to establish these prices. Be sure to discuss the ramifications of such a strategy before using it.

The big picture, however, is that current opportunities are captured and the downside risk is eliminated.

But please do not stop there. Many a producer has sold milk at “desirable” levels, only to watch the market go higher and then later cuss the contract he made. Use a call strategy to allow participation in a potential rising market.

Like I mentioned earlier, no one can predict the market. Even though we may ultimately head to lower prices, the journey toward that point may include several opportunities to capture prices that are higher than presently offered.

For example, you can purchase a $18.50/$20 call spread for the last half of 2011 for approximately $0.37 per cwt.

Simply put, after your sale of $17.54, you can create coverage that spans from $18.50 to $20 per cwt. If the market should go to the magical $20 level, you will be able to participate in such a move with an additional $1.13 (the difference between $18.50 and $20 after your premium cost of $0.37 per cwt …brokerage fees will also need to be subtracted).

Perhaps you are not interested in locking present prices. The second option afforded you is to establish a put option strategy. There are several that exist and you should spend some time with your risk management adviser discussing these many different alternatives. Let me give you the most basic so that you have a benchmark with which to make comparisons.

The most simple put option strategy that exists is to buy one. For example, you can purchase a $16 put for each month in the last half of this calendar year for an average premium price of $0.50 per cwt.

If the market stays above that $16 level throughout the settlement period for each of those last six months, the option will expire without value. If the market should fall to $11, your gain would be $5. If it only dropped to $15 per cwt, your gain would be $1 per cwt.

Essentially, your gain is the difference between your protection level of $16 and the final settlement price. If the market settles higher than $16, then the option will expire without value. There are many other strategies that exist to help reduce the premium, elevate the coverage level, or a combination of the two.

To make that happen, you should expect that you will either accept more risk or pay more premium. You should have a detailed conversation with your risk management adviser concerning such strategies before employing them in your risk management efforts.

The bottom line in all of this conversation is this … Markets move. After having witnessed a move to higher levels and observing the normal trend that exists every three years, the prudent producer will begin taking action now to prevent a move to lower levels from impacting them personally.

We can either acknowledge the reality of the market we are engaged in, or it will work against us. Do not allow 2012 to feel like déjà vu all over again. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

UPDATE: Since the publication of this article, Mike North has left First Capitol Ag and is now the president of Commodity Risk Management Group. Contact him by email .

-

Mike North

- Milk Marketing Specialist

- First Capitol Ag