Happy days are here again. As I write this, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is in record territory, trading above 15,000. The hit song on the kids’ iPods is “Get Lucky.” Optimism for a good 2013 crop has brought feed buying opportunities. And dairy producers seem optimistic that milk prices will go up.

I’m all for positive emotion when it puts a spring in our step and helps us enjoy our life’s work. Go ahead and whistle while you work. And then, when it comes to the markets, keep your emotions in check.

Allow me to illustrate with a true story.

Richard Dennis was a Chicago trader who turned a few thousand dollars into a fortune of more than $200 million by the time he was 35. He then proceeded to teach 12 individuals everything he knew about trading over the course of two weeks.

These 12 became known as the “Turtles,” and for the next 4.5 years they were set loose with Dennis’s investments and earned more than $100 million for him.

A man named Curtis Faith was one of those Turtles. He earned Dennis more than $30 million dollars – the most of any of the Turtles – and chronicled his experience in his book “Way of the Turtle.”

In his book, Faith focuses on the psychological factors that often influence our decision-making, especially with regard to marketing.

View a video interview with Scott Stewart discussing "Way of the Turtle."

I believe there are some real lessons to be learned. He notes, “It’s not about the trading system; it’s about the trader’s ability to execute the trading system.”

More specifically, Faith says, “Human emotion is both the source of opportunity in trading and the greatest challenge. Master it and you will succeed. Ignore it at your peril.”

Dairymen aren’t out to make millions with their milk marketing or feed hedging activities; you are marketing to protect what you work so hard to earn.

It doesn’t matter, though, whether it’s the stock market, the corn market, the milk market or your retirement investments – being more systematic and less emotional is key.

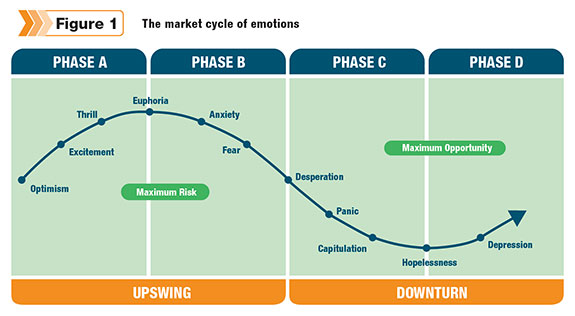

Faith explains, and I concur, that as price movements happen and people become stressed, human emotions – such as fear, hope, greed and despair – begin to influence their decision-making process.

People move from rational thinking to irrational behavior with their marketing decisions, and as a result, this creates repetitive market patterns. The Turtles were trained to recognize those market movements and the opportunities that they signal.

If you are marketing for your own dairy operation, something you have put sweat and blood into, it is incredibly difficult not to be emotional. In bull markets it is easy to be swept into an attitude of “Why hedge to protect risk?

It is just a waste of money, and the market is going to keep going up; this is great!” Conversely, in the deep bear markets, there’s the despair of “Well, I need to start protecting myself so that doesn’t happen again.”

In these emotional bear markets, people make risk management decisions when they actually have the least amount of risk to manage (see Figure 1 ).

The Turtles were on to something: focusing on the market itself instead of how they felt about the market at any given moment.

Beware of these behaviors

What are some of the irrational behaviors that may adversely affect each of us?

Here are a handful of examples from “Way of the Turtle”:

1. Loss aversion – Defined as the tendency to have a strong preference for avoiding losses over acquiring gains, this behavior may sabotage your efforts because you become so focused on trying not to lose money that you fail to see opportunities to make money.

Research has suggested losses can have as much as twice the psychological power of gains.

Faith says, “People affected by loss aversion have an absolute preference for avoiding losses rather than acquiring gains. For most people, losing $100 is not the same as not winning $100. However, from a rational point of view the two things are the same; both represent a net negative change of $100.”

2. Sunk costs effect – This is the tendency to treat money that already has been committed or spent as more valuable than money that may be spent in the future.

For example, have you found yourself saying, “I’ll get out of the market if it gets back up to $X.” Then, as the price keeps dropping, rather than getting out, you start to say, “Well, I’ve already lost this much, what’s a few thousand dollars more?”

3. Recency bias – This is the tendency to weigh recent data or experience more heavily than earlier data or experience. The pitfall here is that you are weighing your future decisions on recent experience, which can often begin to let in doubt and second-guessing.

I think about conversations my advisers had after 2009 with new clients hit hard with the market crash. “We can’t go through another 2009,” they said. Fast-forward three years into a bull market, and producers are saying, “This market has gone up for three years and is only going to go higher.”

Forget the decades of history we have showing a cycle of bull and bear markets: The temptation is very great to weigh recent experiences more heavily.

4. Anchoring – Here, you rely too heavily, or anchor your decisions, on readily available information. We hear the recent high price that a particular commodity hit, and begin to compare and wait and believe the current price looks too low to sell at.

People create mental obstacles – anchors – for themselves, saying, “I can’t get out at this price because that’s where I got in.” What you need to realize is what you pay for something has no relation to what it will be worth in the future, and if the market is going the wrong way, you may need to get out at a loss.

There is no better example than 2012-2013 milk to see this effect in play. Producers get anchored to two things: what was the market high, and what is their cost of production.

• Anchoring to the market high: Too often we see a producer not make a sale because the market price is not quite at the high they could have sold at a month ago.

So they wait, and the market goes lower, then they wait some more, and it goes lower again. Now they end up making a sale far lower than what they would have if their own psychological mindset had not gotten in their way.

• Anchoring to cost of production: The market moves, and when it achieves a high, producers look at their cost of production and get anchored to that price. When it dips below those highs, the producer says, “I can’t sell $17.50 milk; my cost of production is $18!”

It is important to know your cost of production for many reasons. When it comes to the markets, however, I’ll let you in on an ugly truth: The market simply does not care what your cost of production is.

Just because your cost of production might be $18 at a point in time does not mean the Class III price will get above that price. Your goal is to build a strong weighted-average price over time, not try and lock in margins that may never materialize.

5. Bandwagon effect – We start to believe things, and act accordingly, because many other people believe them. Our dairy team leader, Matt Mattke, had one of his biggest déjà vu moments this year when a client said to him, “I talked to 10 of my fellow dairy producers, and they all think this market is going to continue to go up for some time.”

Why is this déjà vu? Matt heard the same comment in 2008. When you’re feeling an emotion, others in your situation are likely to be feeling a similar emotion.

It’s not about you

In the end, what you are feeling, or what anyone else is feeling, is not important. Rather, a marketer’s success is determined by adherence to the systematic approach you have in place. The Turtles proved that.

I like to explain this in baseball terms. A good batting average is 300, which means 70 percent were misses. So, even though you missed most of the time, you still end up with a positive batting average.

The same is true in the market. You can be wrong more often than right. However, if you limit your losses, your gains can be much larger than your losses, and you could end with a positive position in the market.

If you focus on the 70 percent that were poor decisions, you’ll cloud your judgment. Each decision must be made in the present – not based on the past or the future. PD

Stewart is the CEO of Stewart-Peterson Inc.